Approximately nine years ago, I founded a company specializing in developing new ways to invest in and hedge against inflation. I originally had two partners; one left after a few months and the other lasted a year before heading back to a Wall Street job. (I think leaving after 3 months of trying a startup was a little sporty, but I don’t begrudge the partner who stuck it out for a full calendar turn and then some.)

The last nine years have been a difficult time to be developing and marketing inflation expertise. While we conceived the firm as having strategic positioning on inflation protection – whether inflation is going up or down, inflation risk is always there to be managed…and we are all born inflation-exposed, and remain so unless we do something about it – I confess that I underestimated how hard of a pitch that would be to investors who haven’t seen core inflation above 3% for two decades. Unless you have a certain amount of grey hair, you think 3% is high inflation, but that’s not really high enough to damage most asset markets. So why bother?

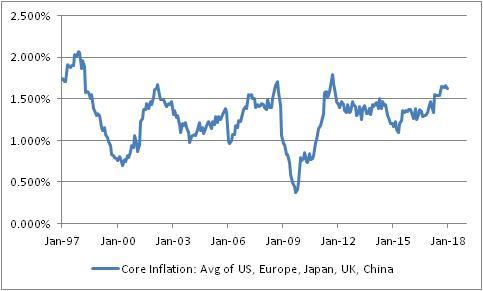

But times, they are a-changin’ back (as Bob Roberts famously sang). Average core inflation around the world is near the highest levels since the 1990s. The chart below shows the unweighted average of the US, Europe, Japan, the UK, and Chinese core inflation (using median for the US, which is a better measure). While the average of 1.7% or so is nothing to be terrified about, it also should be noted that there is nothing evident on the horizon that would tend to arrest this rising trend.

While money supply growth has been slowing gradually around the world, monetary conditions are not likely to seriously tighten until banks are no longer sitting on a mountain of excess reserves. In the meantime, higher interest rates will tend to cause money velocity to rise because velocity is the inverse of the demand for real cash balances – in English, that means that when interest rates are low, you’re happy to hold cash balances but when interest rates rise, cash becomes a hot potato to be invested, spent, or lent rather than sitting in cash. It is no coincidence that both global money velocity and global interest rates are both at or near all-time lows. However, interest rates seem to be going higher – seemingly nowhere faster than in the US, where the 5y Treasury rate has risen about 80bps in the last five months and is at 8-year highs. In turn, that means money velocity is very likely to rise, and any rise at all makes it harder to have an agreeable mix of growth and inflation.

Leave A Comment