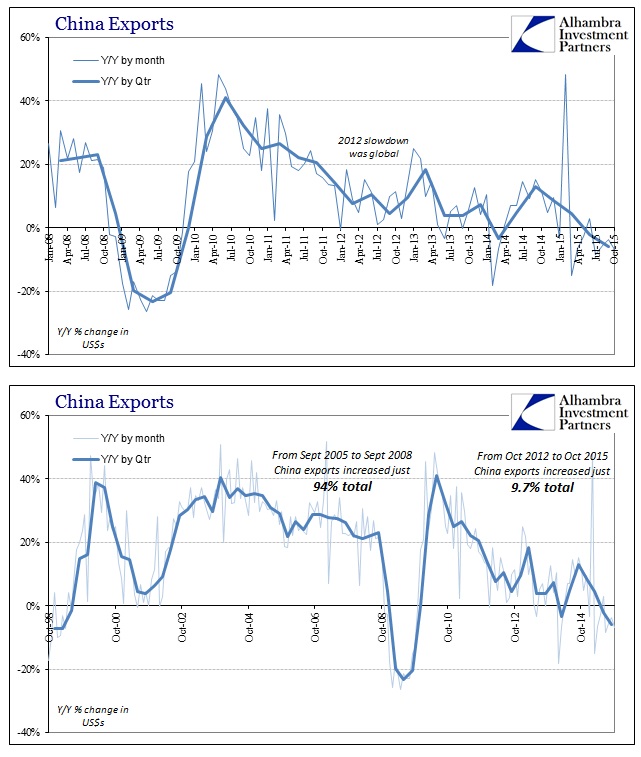

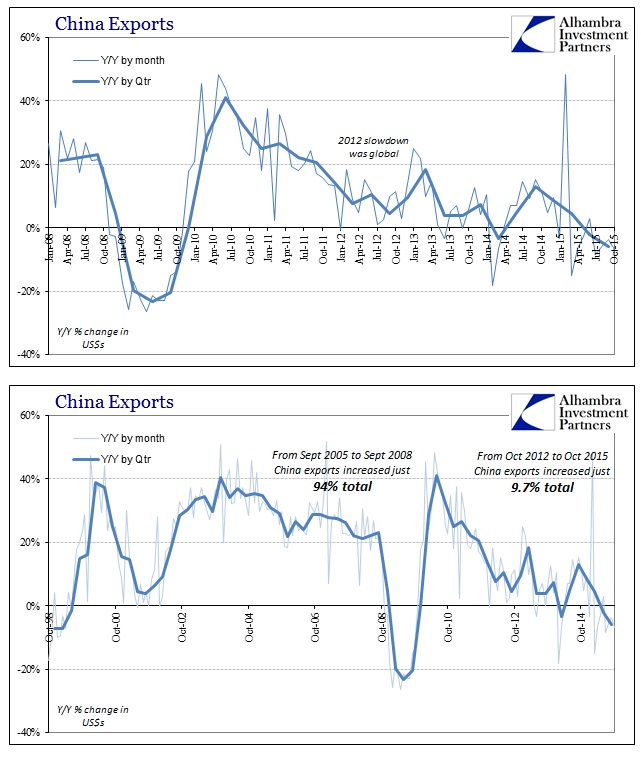

The unrelenting economic decline in China is finally getting the attention of economists and the media as something more than a big problem “for them.” Imports declined by 18.8% in October after having contracted by 20.5% in August. On the export side, Chinese goods sent abroad fell 6.9% year-over-year in dollars which confirms that the contraction is not China’s alone and, more importantly, continues on without as much as the smallest reaction to all the global “stimulus” (and persistent threats thereof).

While nobody can seem to figure out why there is no response to monetary “easing” even in China, with the PBOC having cut its benchmark six times in the past year while also cutting domestic bank reserve requirements by 300 bps just since February 4, at the very least the overwhelming tendency to just ignore it all as trivial has finally been battered into submission and thus broad admission.

China’s exports fell in October for the fourth consecutive month, as a once-powerful engine of the country’s growth continued to sputter in the face of weak global demand.

The world’s appetite for goods from China—the world’s second-largest economy accounts for nearly one-fifth of global factory exports—has been lower than expected this year. Meanwhile, weak domestic demand continues to reduce imports. Both are contributing to China’s growth slowdown. “The mix of the data is again not encouraging,” said Commerzbank economist Zhou Hou. “Trade momentum is unlikely to turn around in the near term.”

For the longest time, descriptions of China’s economic descent focused only on its internal bubbles rather than the reason for their more recent reversals. The PBOC is faced with little plausible alternative to attempting to manage the bubbles as best as it might (however low probability that might be) which is what the import implosion reflects. That adjustment is entirely made as the global recovery first ended (2012) and now is reversing (2015). China was built up in the 21st century to service the euro/dollar world of huge global trade expansion; without that “dollar” tailwind it all falls apart.

With the slowdown in Chinese exports past the midpoint of its fourth year, it was perhaps inevitable that the PBOC would run into unmanageable imbalance. There is significant self-reinforcing cycles at work, but overall that lack of recovery is driving the “dollar” as the “dollar” hits global trade. The August liquidations and PBOC “devaluation” were an indirect response to the end of “transitory” in the global economy, especially as the US economy no longer suggests one contrary outlet of optimism and hope.

Leave A Comment