This week’s collapse of the Turkish lira has dominated the headlines, and it is widely reported that this and other emerging market currencies are in trouble because of the withdrawal of dollar liquidity. There are huge quantities of footloose dollars betting against these weak currencies, as well as commodities and gold, on the basis the long-expected squeeze on dollar liquidity is finally upon us.

Doubtless, Triffin’s dilemma is dominating these speculators’ thoughts, telling them demand for the dollar as the reserve currency is infinite. This article points out that foreign financial entities as a whole already possess most of the excess liquidity created by the monetary expansion of the dollar since the Lehman crisis. Admittedly, ownership of dollars is unlikely to be evenly distributed across correspondent banks representing all foreign nations. But this is no reason to say dollars are not under-owned by foreign users, and we must not forget dollars are also available in the foreign exchanges, as always, for credible buyers. Nor must we forget that the reason for the enormous quantity of currency derivatives ($75 trillion in US dollars alone[i]) is that future demand for dollars is already significantly hedged.

No, the reason certain EM currencies are losing purchasing power is the fault of individual governments and their central banks, who do not seem to realize that their unbacked fiat currencies are valued purely on trust, both that of their own people and on the foreign exchanges. And as we should know, trust is not something to be toyed with.

Furthermore, comments that China is in trouble from trade tariffs and being undermined by a strong dollar are wide of the mark. Geopolitics dominates here. America’s occasional successes in attacking the rouble and yuan are no more than transient pyrrhic victories. She is not winning the currency war against China and Russia. China is not being deflected from her strategic goals to become, in partnership with Russia, the Eurasian super-power, beyond the reach of American hegemony.

This article looks beyond the short-term rush into the dollar, which is driven predominantly by hot money, to gain a more balanced perspective on the dollar’s future.

Collapsing currencies are nothing new

Collapsing currencies are becoming widely discussed. Until recently, it was Venezuela, once supported by luminaries such as Professor Stiglitz, that hogged the headlines on collapsing currencies.[ii] That has now changed because President Trump has started to throw his weight around. The Iranian rial, the Turkish lira, and the Russian rouble have all suffered, mainly due to American currency and trade sanctions, triggering a loss of international confidence in their currencies. Even the Chinese yuan, surely that most managed of currencies, is down 9% from its peak in April.

With some 180 currencies backed by nothing other than the faith and credit of their issuers, there will always be winners and losers, with more losers than winners when measured against a strengthening dollar. Doubtless, monetary policy has much to do with it, with the Fed leading the way on tightening, and many other central banks not even reluctantly following.

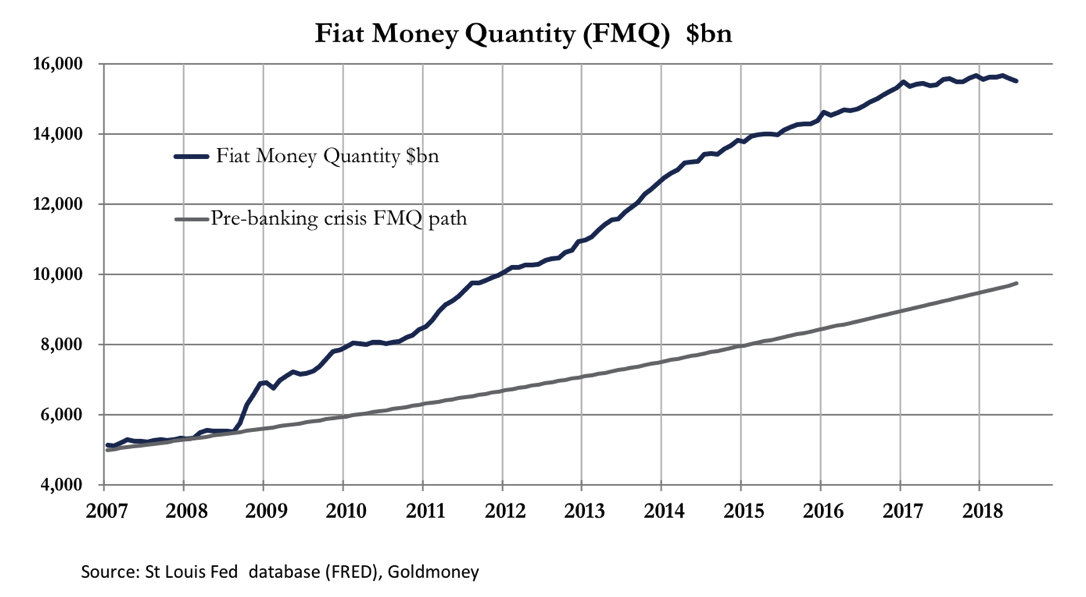

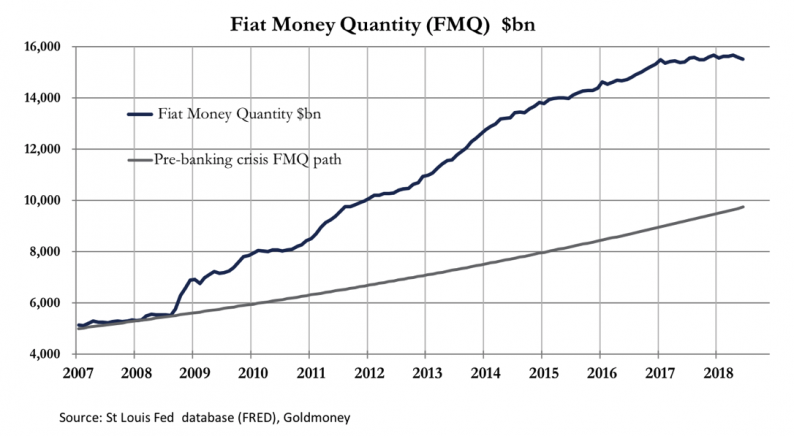

To illustrate how much the monetary environment has changed in recent months, it is worth looking at the fiat money quantity, which is essentially the sum of true money in circulation (mainly cash, checking accounts and deposits) plus bank reserves (commercial bank deposits) on the Fed’s balance sheet.[iii]

The chart above shows that by last June, FMQ had stated to contract, as the fall in reserves on deposit at the Fed began to bite and the growth in bank deposits has stalled. The chart also shows that FMQ is still $5.8 trillion above its pre-crisis growth path. Despite this, the small rise in the Fed Funds Rate, coupled with the contraction of bank reserves is driving commentators to worry about a developing global liquidity crisis.

In last week’s article, I pointed out that since the dollar abandoned all pretense at being backed by anything other than public trust, there has been no correlation whatever between higher interest rates and the rate of monetary expansion.[iv] Commentators should, therefore, look elsewhere for evidence of illiquidity.

The contraction of bank reserves on the Fed’s balance sheet involves money, not in public circulation, so the question arises as to whether their contraction restricts bank lending. The answer must be an emphatic no because when reserves totaled less than $10bn through most of 2007-08, there was no problem expanding bank credit. True, there have been rule changes aimed at reducing the maximum level of bank balance sheet gearing, but at just short of two trillion dollars of bank reserves, we are nowhere near bumping into that headroom.

Leave A Comment