China’s trade estimates continue the trend of the global economy pushing closer to recession, assuming that it is not already there. We know that the lower part of the global supply chain below Chinese manufacturing and assembly, the resources and materials flow, has already been pushed beyond simple recession in some places, like Brazil, into defining a new disastrous economic state. What is left arguable is the end markets that precede all of this where economists and economic forecasts simply dismiss increasingly dark financial indications, especially commodities but not limited to them, as if the global supply chain were in high working order at the top but mysteriously chaotic just underneath.

That view is, of course, absurd. There are feedbacks and amplifications (and counterbalances) to consider, but the obvious track in these kinds of economic reflections are all working in the same direction; the one far and away from recovery in any part. That is why oil traded today below $37, copper threatens to trade below $2 and swap spreads continue to find new ways to overtake, perhaps, yield curve inversion.

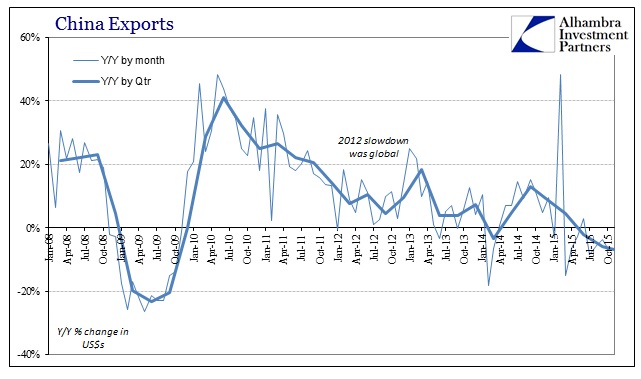

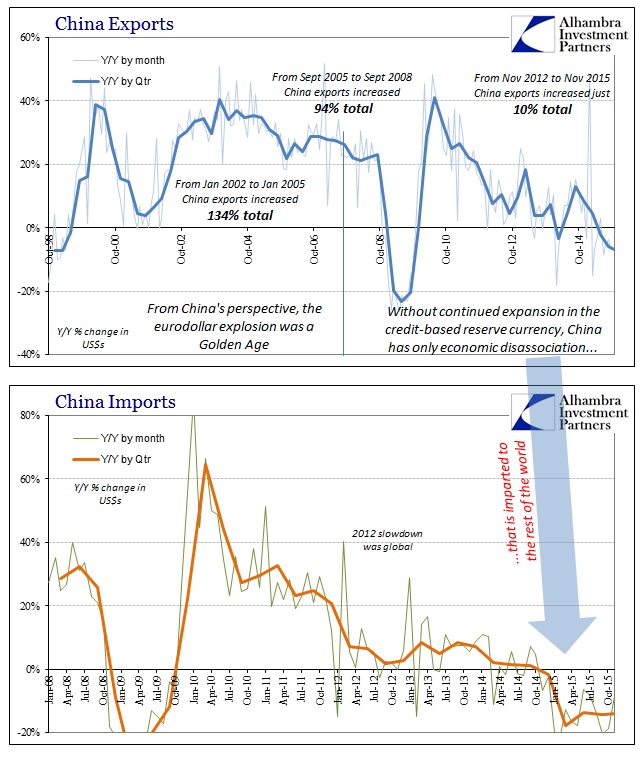

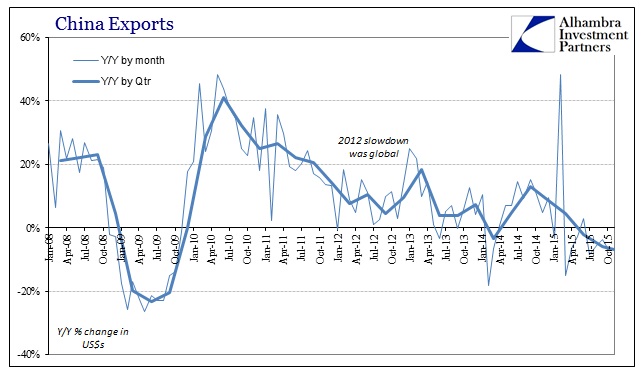

Exports declined by nearly 7% in November in China while imports were marginally better than October at -8.7%. For the global supply chain, neither of those figures truly deliver the full extent of the economic disassociation. China’s imports in November 2015 are down almost 15% from November 2013, and a little more than 10% lower than November 2011!

It is, however, the export side that drives the industrial machine in China, stretched now beyond blatant overcapacity. The reason for that is decidedly simple given China’s history with the eurodollar expansion – and now decline.

China was built, quite literally, with eurodollar finance funding industrial expansion to service eurodollar finance funding more and more consumption in end markets, especially the United States. In the early part of the housing mania, from January 2002 through January 2005, Chinese exports grew 134% (a surge reflected by proportional increase in the PBOC’s monetary functioning). Even after the housing bubble burst here (and for Europe) and the trend began to slow, China’s exports surged by 94% from September 2005 through September 2008. By comparison, in the past three years China’s exports have grown 10%; not per year, total. When 20-40% year-over-year growth is your economic baseline, -3% (so far in 2015 YTD) is near catastrophic.

Leave A Comment