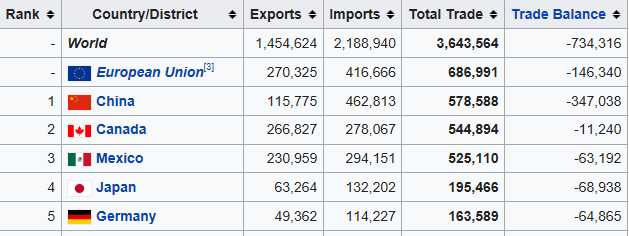

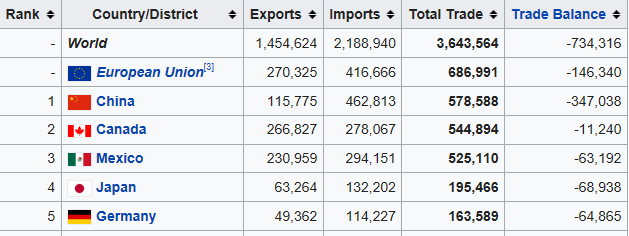

U.S. international economic policy entered into a new aggressive phase last week. Initially, the Treasury Secretary, Steven Mnuchin, called for a weaker U.S. dollar as a major tool to reduce the U.S. trade deficit. Then, the U.S. Administration introduced new tariffs on solar panels and washing machines. U.S. Secretary of Commerce, Wilbur Ross, raised the prospects of a trade war when he warned that “the U.S. troops are now coming to the ramparts”. Government officials have put U.S. trading partners on notice that this is just the start of protectionist policies aimed at the U.S. trade deficit. We can expect further unilateral actions by the United States, especially against Chinese imports. The United States runs a total trade deficit of $750b, the largest deficit being with China ($347b), followed by the EU ($146b), Japan ($68b), Mexico ($63b) and Canada ($11b).

Figure 1 US Trade Data 2016

Trump’s international economic policy fails to understand how trade deficits and capital flows are part of a nation’s balance sheet. A first-year university student of international economics knows that a policy affecting one side of the accounting ledger (trade flows) will have an opposite effect on the other side of the accounting ledger (investment flows) in order to bring the overall balance to zero. Just as double entry booking principles apply to corporate balance sheets, so does it apply to a nation’s balance sheet.

To begin with, the United States runs trade deficits with nearly 100 countries because it consumes more than it produces. Its major trading partners, especially in the EU and Asia, consume much less than they produce, offering their surplus production to the U.S. consumers. The United States, in turn, pays for its net imports with U.S. dollars which its trading partners willingly use to purchase U.S. government securities. Nearly half of the U.S. government debt is owned by China and Japan. Trade deficits are financed with capital inflows such that the overall international balance remains at zero.

Leave A Comment