Excess reserves of depository institutions peaked at $2.7 trillion in August of 2014. By December of 2016, excess reserves fell to $1.9 trillion but have since climbed back to $2.2 trillion.

On October 3, 2008, Section 128 of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 allowed the Federal Reserve banks to begin paying interest on excess reserve balances (“IOER”) as well as required reserves. The Federal Reserve banks began doing so three days later.

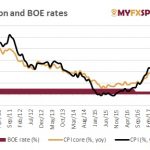

As interest rates have risen, so has the free money to banks.

Excess Reserves

Interest Paid on Excess Reserves

At 1% interest, banks receive $22 billion in free money every year, nearly all of that goes to the largest banks.

Banks Paid $22 Billion to Not Lend?

Some argue that banks have an incentive to not lend, simply to collect interest.

Mathematically, it does not work that way. Excess reserves are a function of the Fed’s balance sheet and those reserves do not change whether a bank lends more or not.

A discussion of Interest on Excess Reserves and Cash “Parked” at the Fed on the New York Fed Liberty Street website explains.

Reserve balances that are in excess of requirements are frequently referred to as “idle” cash that banks choose to keep “parked” at the Fed. These comments are sensible at the level of an individual bank, which can clearly choose how much money to keep in its reserve account based on available lending opportunities and other factors. However, the total quantity of reserve balances doesn’t depend on these individual decisions. How can it be that what’s true for each individual bank is not true for the banking system as a whole?

The resolution to this apparent puzzle is that when one bank decides to hold a lower balance in its reserve account, the funds it sheds necessarily end up in the account of another bank, leaving the total unchanged.

In the aggregate, therefore, these balances do not represent “idle” funds that the banking system is unwilling to lend. In fact, the total quantity of reserve balances held by banks conveys no information about their lending activities – it simply reflects the Federal Reserve’s decisions on how many assets to acquire.

Leave A Comment