As every holiday movie watcher knows, it’s your Christmas spirit—the very power of your belief—that gives Santa’s reindeer the get-up-and-go to deliver a sackful of toys. But like those woebegone characters who openly question the very existence of gift-bearing emissaries from the frozen north, we doubted Valeant’s ability to wring new sales from old drugs, to conjure organic growth from existing brands facing generic competition. Shareholders had a party, and we were grumpily bah-hum-bugging over by the bar. We didn’t believe.

And so, in the midst of this holiday season, we are gathered here today to announce our triumph over doubt, our victory over misgivings, and our embrace of the festive spirit. What ghostly portend of a ghastly Christmas future has restored us to the faithful flock? Well, like Scrooge before us, first we need a look at Christmas past.

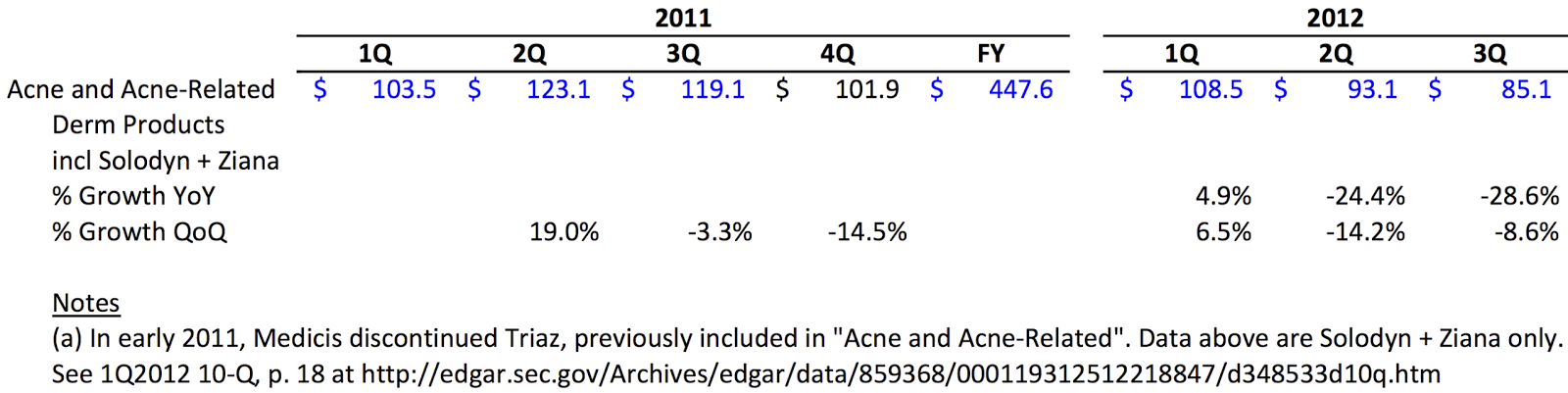

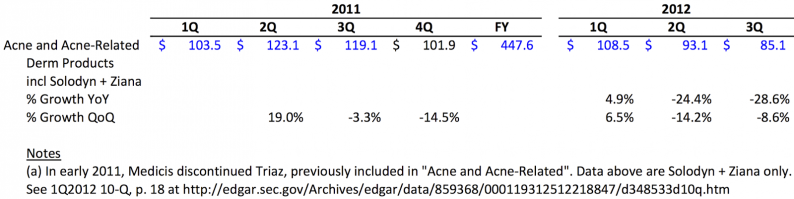

Valeant completed the acquisition of Medicis on 11 December 2012, almost three years ago today. And before Valeant’s warm embrace, sales of Medicis’ acne treatment Solodyn had fallen through the ice, so to speak, according to the respective 10-Q filings:

A Marketwatch article told the tale:

[Valeant] stock has fallen back amid worry that sales of Medicis’s blockbuster drug, Solodyn, may be declining faster than expected.…

Solodyn generates about 40% of Medicis’s annual sales, analysts say. Morgan Stanley & Co. estimates the treatment accounts for around 75% of the company’s earnings per share. A Medicis representative declined comment. Valeant Chief Executive Michael Pearson, in an interview, said he agreed with the 40% revenue estimate, but declined comment on the profit projection.

Some analysts are taking issue with the drug’s growth prospects, amid signs of flagging sales. Solodyn prescriptions in the U.S. fell 44% during the last week of August from a year earlier, according to data from IMS Health, a healthcare information company. In the first two months of the third quarter, Solodyn prescriptions fell 24% from the first two months of the second quarter, according to Piper Jaffray & Co., based on IMS data.

On Sept. 14, Morgan Stanley downgraded Valeant to equal weight from overweight, “concerned about Solodyn’s growth outlook.”

But Valeant was unbowed. While its forecast of $250-$275M (p. 10) in sales for Solodyn in 2013 was far too high (actual was ~$200M, p. 5), a fairly sizeable decline from what we can see of 2012), sales appear to have stabilized in 2014 ($210M, p. 9) and even started growing again (LTM: $250M, #7 product worldwide as of 3Q15, p. 5).

Forgive the mixed metaphor, but another holiday tale provides a nice summary: sales of Solodyn that could barely satisfy Wall Street for another quarter (give or take) have miraculously lasted more than eight quarters (give or take).

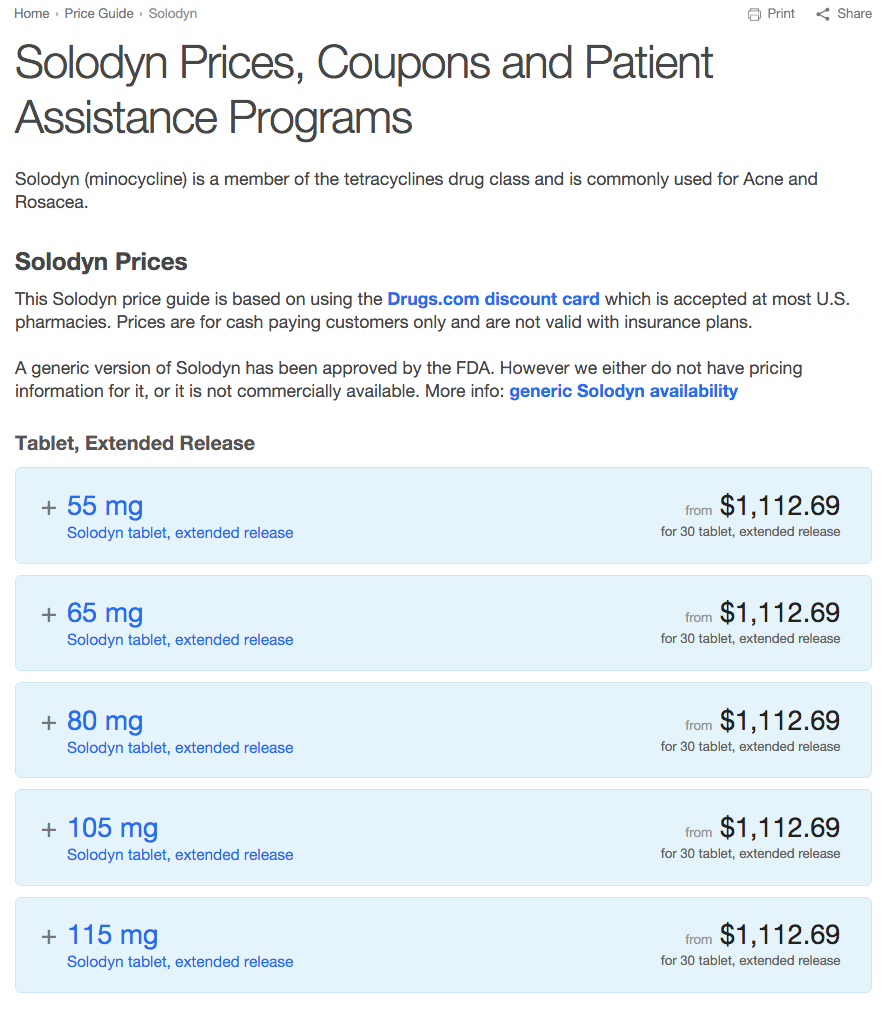

During this time, retail prices of Solodyn have climbed from about $700 in 2011 to over $1100 for a 30 day supply. On Valeant’s account, they sold more pills at higher (list) prices, despite competition from cheap generic alternatives. A holiday miracle, indeed.

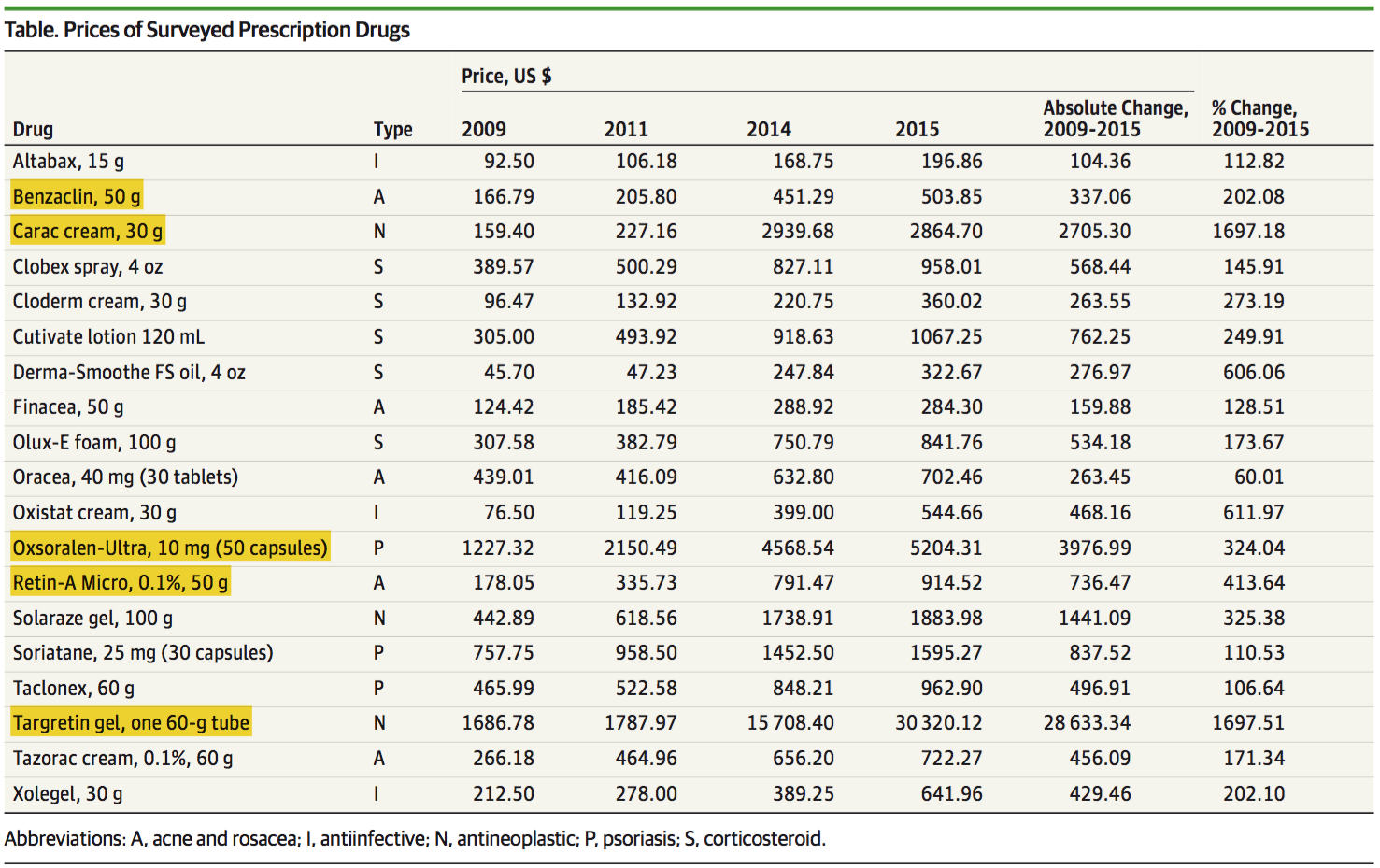

But how? How can you sell more volume of an old drug at a higher list price while facing generic competition? In fact, a recent article in JAMA Dermatology made the observation, after checking retail prices of several dermatology drugs over a six-year period, that prices for Valeant’s drugs had risen the most.

The ValeantNow PR commandos, quick to the barricades, helpfully pointed out that Valeant sells a lot of dermatology drugs and that they didn’t own these for the entire period, just lately. Apparently retail prices rise of their own volition, and the fact that “these products faced generic competition” makes such increases less notable, not more. (Note to analysts: we see the opportunity for more “cost synergies” in the marketing department: at Valeant, prices self-levitate.)

Generous to a fault, Valeant takes pains to remind us that its net prices have risen much more modestly. On the 3Q15 conference call, Mike Pearson said (p. 7):

As most of the commentary around price centers on the wholesale price or list price, we wanted to provide a more clear picture on what Valeant actually realizes from a price action, which is considerably different than what has been portrayed. If you look at the top 10 dermatology products, which represent approximately 62% of our dermatology portfolio, we took, on average, a 14% gross price increase on these products this year, yet we realized less than a 2% price increase on a net basis.

In reality, we increased price on 85 of our 156 branded pharmaceutical products, or 54% of our products. And our average gross price increase was 36%. It is important to note that our realized price increase was 24%.

Furthermore, Valeant’s “patient assistance” (aka “access”) contributions to unnamed foundations grew far faster than its revenue, at a rate of 128% compounded from 2012 to 2016 (p. 5), reaching a projected total of ~$1B in 2016. And yet a recent presentation states 14% of “organic growth” in the “promoted branded Rx business” was due to “gross-to-net adjustments” (p. 86). As net revenue is gross minus “cash discounts and allowances, chargebacks, and distribution fees…as well as rebates and returns” (p. 33)—things that make net less than gross—doesn’t growth from gross-to-net adjustments mean a decrease in a discount? Meaning net prices rise? (Also, discounts can shrink only so much before disappearing; perhaps a better name for paying someone cash to buy one’s drug would be “subsidy.” Colour us curious as to how “durable” this source of organic growth will prove.)

Point being, this is befuddling. Apparently Valeant risked widespread public opprobrium, unwanted press attention, the ire of Congress, and even federal investigations for what we are told is a minor benefit to realised prices. And nobody, apparently, pays list prices. So why did they raise them? And if they hadn’t raised gross prices, would net prices have declined? And if the explanation for the gross-to-net difference is the stunning growth in rebates and discounts, what is the point of raising prices only to, in essence, give out lots of coupons, except in the hope that such coupons don’t get used? Giving someone gold so they can purchase your frankincense and myrhh is a strategy, I suppose.

You can see why we were perplexed. We didn’t believe they could raise prices, grow volume, and increase “organic growth.” And, defying us, they did it. How? Well, Valeant pretty much told us. In two words: “alternative fulfilment.”

Here’s then-CFO Howard Schiller describing, at the Goldman Sachs Healthcare Conference on June 11, 2013 (p. 7), the improvements Valeant made to Medicis’ original program. (Note: Two weeks later, Philidor would receive its first pharmacy license in Pennsylvania, having signed a contract with Valeant within its first month of existence.)

Howard Schiller, CFO, Valeant

So I probably think under Medicis, alternative fulfillment was held out a little bit too much as the holy grail. I really think it’s — it’s actually the starting points, and in some ways, it was quite a clumsy starting point. It wasn’t that different, but it’s a process where we have generation two and generation three. But it’s all trying to focus on profitable scripts, and stay away from those scripts that are unprofitable, and more judicious use of co-pay cards and the rest, and making sure when a customer, a patient is covered, you get reimbursed for it.

Leave A Comment