One month ago, we first highlighted a troubling development for China’s banking system, one which we called the “Great Shadow Unwind” and which showed that entrusted loans, a broad proxy for China’s unregulated ‘shadow banking’ system, contracted for the first time since 2007, confirming Beijing’s ongoing crackdown of China’s runaway $8.5 trillion shadow banking system. Well, overnight, the PBOC released its latest Chinese loan data, and it had several notable highlights, most of which got lost in today’s overall noise.

First, the one aspect of the latest Chinese data most commentators focused on and discussed, was the collapse in China’s M2 aggregate to just 9.6%, which not only missed expectations of 10.4%, but was also the lowest print on record.

However, unlike most developed nations, M2 in China has largely become an anachronism from China’s pre-shadow banking past, which excludes many of the broad monetary-equivalents in circulation. This is how Goldman explained this morning why those concerned about the plunge in M2 growth shouldn’t lose much sleep: “We put more weight on the adjusted total social financing data, because M2 data are heavily distorted by borrowings between financial institutions which may have relatively limited impacts on the real economy, though TSF has its own problems– such as not including all forms of financing, especially newly developed ones.”

Touching on the plunge in M2, on the PBOC’s website, the central bank explained that slower M2 growth was a result of declining leverage, and the implementation of a “prudent, neutral monetary policy, and intensified supervision that has compelled the financial system to reduce leverage,” adding that as deleveraging continues, “slower M2 growth than in the past will become a new normal.”

Which, in turn brings us to the far more important, for China, loan number: Total Social Financing – a monetary aggregate that captures both traditional bank loans as well as shadow loans, including trusted, entrusted loans and undiscounted bankers accepetances, which in May likewise dropped to CNY 1.06tn, missing consensus estimates of CNY 1.19tn and down from 1.39 tn in April.

And while the PBOC has aggressively clamped down on shadow financing, the central bank has refrained from cutting off traditional bank loans to companies, aiming to support growth. And, sure enough, in May China’s new Yuan loan creation did beat estimates modestly, rising by CNY1.11tn vs CNY 1tn expected. This number is hardly anything to write home about however, because as Goldman explains, “strong broad credit growth is mainly a reflection of continued strength in credit demand and the willingness of the central bank to maintain just enough liquidity to the real economy to maintain growth at the current near-trend level. This is likely the main driver of stronger RMB loan growth in April and May, which offset the fall in non-loan credit in total social financing data.”

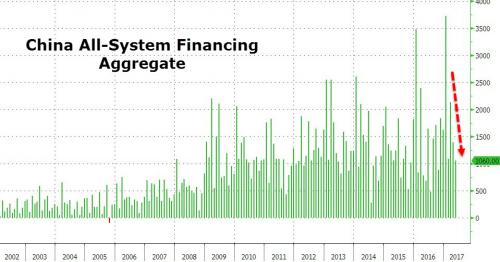

But while loan growth was stable, it was the broader TSF which demanded further attention, not least of all because – by definition – it should be bigger than its loan component. Since that was not the case, it suggests that one or more of the other TSF components declined. But before that, here is a look at China’s broadest credit growth on a annual basis: just like M2, the slowdown in the overall growth rate is, while not quite as sharp, quite visible and is a bright red flag that China’s credit impulse is turning sharply negative.

Leave A Comment