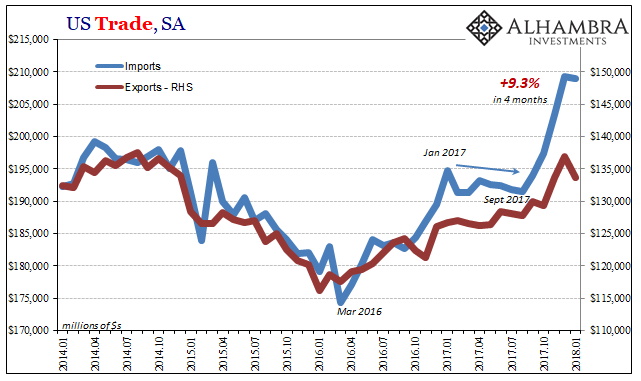

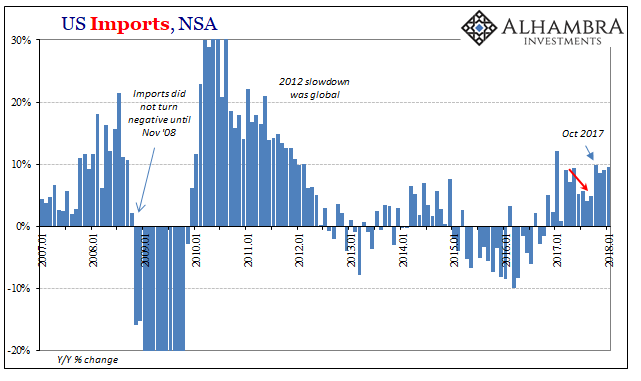

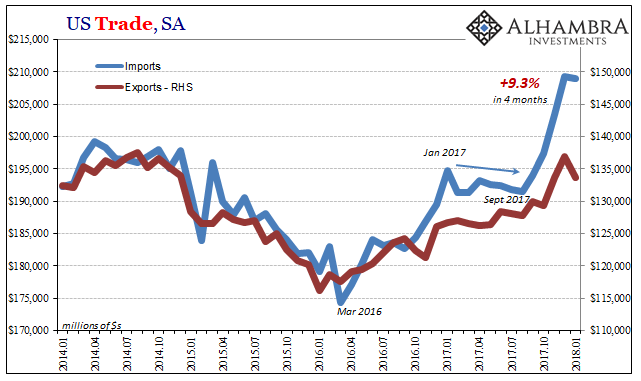

After an incredible run, up nearly 10% in just four months, imports took a break in January 2018. Year-over-year, not seasonally-adjusted, imports gained 9.5%, a rate that is better than experienced during the similar upturn in 2014 but still well short of what the rest of the world requires for global growth. The fact that almost all of that gain came during the aftermath of Harvey and Irma at this point raises doubts as to whether US demand will be sustained even at this low level.

As with other economic accounts in December and January, the rolling over strongly suggests the artificial boost of the hurricanes’ collective aftermath. In terms of imports, this was an especially strong response. Inbound trade had between January 2017 and last October contracted again, signaling the opposite of “globally synchronized growth” (unless growth in this context included that negative signs).

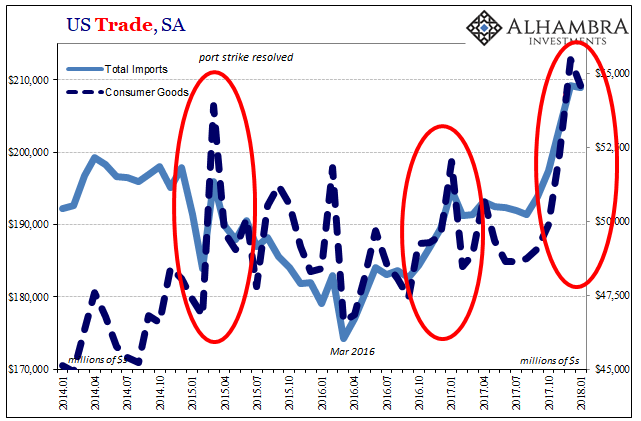

The very sharp rise particularly in the sector of trade driving it, consumer goods, proposed the artificiality of the trend. Rather than recognize that for what it likely was, instead there was a rush to see the dramatic upswing as, well, a lasting dramatic upswing – to the point now that the import side in particular is being used to justify tariffs and the impetus for a trade war.

It’s that last part that is truly unfortunate, not because I believe tariffs will have much of an economic effect way one or another. Rather, they are emblematic of what I believe is the worst case – the further fragmentation of the political and social order that in one sense needs to happen but at the same time opens the door to far greater risks of where the clear lessons of history are forced silent.

The issue isn’t US trade, but the distinct lack of global trade at all. The trade deficit is a symptom or even byproduct of the eurodollar system as it is. Just as with immigration or robots, the fact that the rest of the world (primarily China) holds a mercantile surplus against the US is the wrong place for focused attention. It’s understandable to a degree, at least like now when legitimate economic criticism is often forbidden. The economy has recovered, so we are told, therefore something else has to take the blame – because there is blame.

Leave A Comment