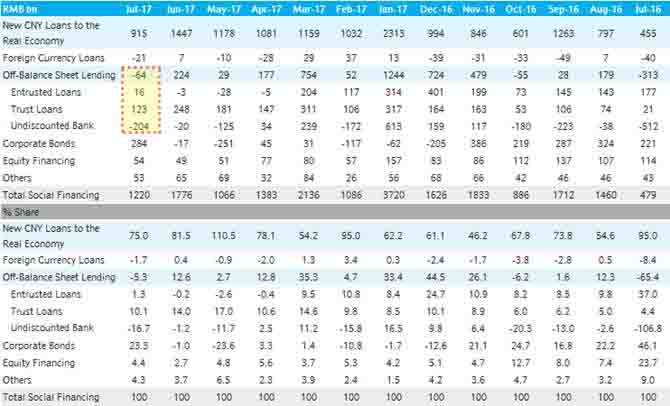

When we discussed the latest monthly Chinese credit data reported by the PBOC, we pointed out something which to most pundits was broadly seen as success by the Politburo in its deleveraging efforts: for the first time in 9 months, debt within China’s shadow banking system – defined as the sum of Trust Loans, Entrusted Loans and Undiscounted Bank Loans – contracted. These three key components combined, resulted in a 64BN yuan drain in credit from China’s economy, the first negative print since October 2016, and rightfully seen by analysts as evidence that Beijing’s campaign to contain shadow banking and quash risks to the financial system, is starting to bear fruit.

Offsetting this unexpected decline in shadow bank credit (if not Total Social Financing) was a greater than expected increase in traditional yuan bank loans. As we observed last Tuesday, both corporate loans and household loans increased greater than last year; new corporate loans advanced to CNY354bn from a decline of CNY3bn a year ago, with long-term corporate loans contributing CNY433bn (a year ago: CNY151bn) and short-term loans adding CNY63bn (a year ago: CNY-201bn). New household loans registered CNY562bn, compared with CNY458bn a year ago.

So far, so good: after all a transition from the largely unregulated, and speculative shadow bank issuance to conventional bank issuance is just what the PBOC, China’s regulators and most importantly, Xi Jinping want ahead of this year’s all important Congress. Furthermore, the fact that China’s economy continues to grow at a healthy pace, even if it means creating the occasional industrial metals bubble…

…. thanks to healthy bank loan creation, is good for both China and the rest of the world, and suggests that despite the sharp drop in China’s credit impulse, there is more where it came from.

There is just one problem: there very well may not be much where it came from. In fact, according to analysts, there may be almost nothing left.

Leave A Comment