Total income earned can be divided into what is earned by labor in wages, salaries, and benefits, and what is earned by capital in profits and interest payments. The line between these categories can be a blurry: for example, should the income received by someone running their own business be counted as “labor” income received for their hours worked, or as “capital” income received from their ownership of the business, or some mixture of both?

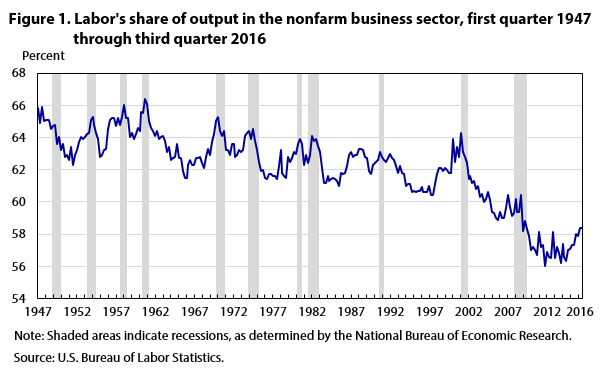

However, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics has been doing this calculation fordecades using a standardized methodology over time. The US labor share of income was in the range of 61-65% from the 1950s up through the 1990s. Indeed, for purposes of basic long-run economic models, the share was sometimes treated as a constant. But in the early 2000s, the labor share started dropping and fell to the historically low range of 56-58%. Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman provide some perspective on what has happened, citing a lot of the recent research. in “Trends in Factor Shares: Facts and Implications,” appearing in the NBER Reporter

(2017, Number 4).

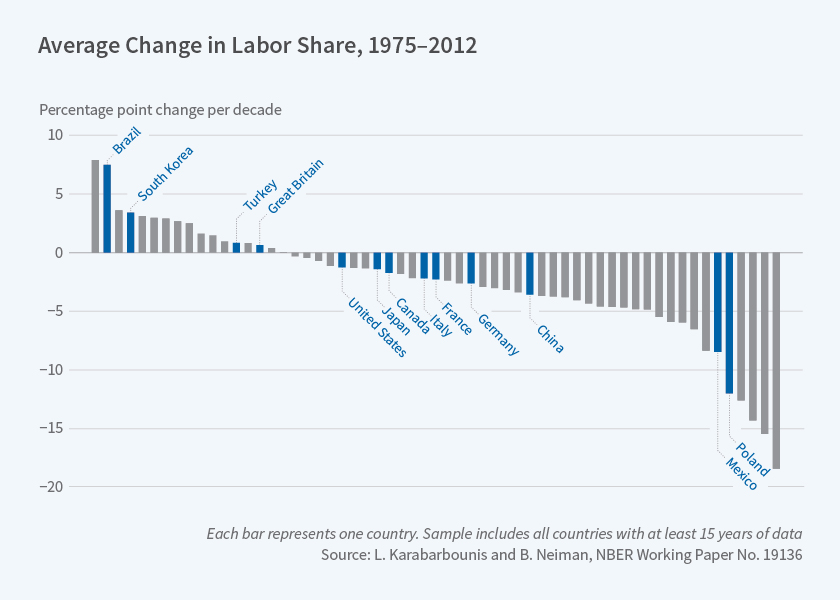

They built up a data set for a range of countries, and found that many of them had experienced a decline in labor share. Thus, the underlying economic explanation is unlikely to be a purely US factor, but instead needs to be something that reaches across many economies. They write: “The decline has been broad-based. As shown in Figure 1, it occurred in seven of the eight largest economies of the world. It occurred in all Scandinavian countries, where labor unions have traditionally been strong. It occurred in emerging markets such as China, India, and Mexico that have opened up to international trade and received outsourcing from developed countries such as the United States.”

They argue that one major factor behind this shift is cheaper information technology, which encouraged firms to substitute capital for labor. They write:

Leave A Comment