One of the things you might have noticed if you follow trends in global growth and trade, is that the entire world seems to be decelerating in tandem with China’s hard landing (which most recently manifested itself in another negative imports print).

For evidence of this, one might look to the WTO, whose chief economist Robert Koopman recently opined that “it’s almost like the timing belt on the global growth engine is a bit off or the cylinders are not firing.” And then there’s the OECD, which recently slashed its global growth forecasts. The ADB joined the party as well, citing China, soft commodity prices, and a strong dollar on the way to cutting its regional outlook. Even Citi has jumped on the bandwagon with Willem Buiter calling for better than even odds of a worldwide downturn.

Indeed, virtually anyone you talk to will tell you that the world looks to have entered a new era post-crisis that’s defined by a less robust global economy. Those paying attention will also tell you that this dynamic may well end up being structural and endemic rather than transitory.

Earlier today, we noted that Credit Suisse’s latest global wealth outlook shows that dollar strength led to the first decline in total global wealth (which fell by $12.4 trillion to $250.1 trillion) since 2007-2008.

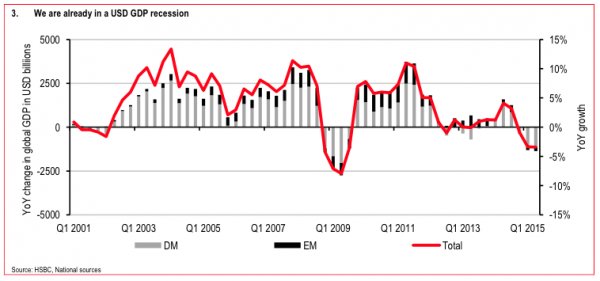

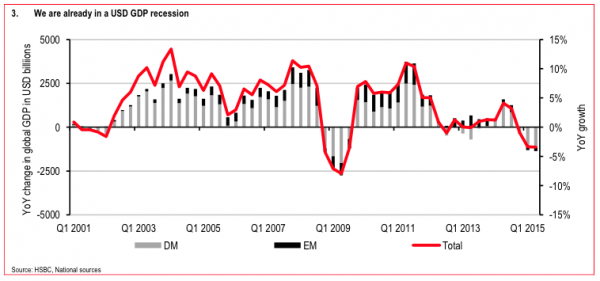

Interestingly, a new chart from HSBC shows that when you combine the concepts outlined above, you learn that when denominated in USD, the world is already in an output recession.

Some color from HSBC:

We are already in a global USD recession

Global trade is also declining at an alarming pace. According to the latest data available in June the year on year change is -8.4%. To find periods of equivalent declines we only really find recessionary periods. This is an interesting point. On one metric we are already in a recession. As can be seen in Chart 3 on the following page, global GDP expressed in US dollars is already negative to the tune of USD1,37trn or -3.4%. That is, we are already in a dollar recession.

We arrived at these numbers by converting global GDP into USD terms and then looking at the change in GDP. True, this highlights to a large extent the impact of a stronger dollar – which may be unfair, but the US dollar is still the world’s reference currency. However, it highlights that from a US perspective the global growth outlook is rather challenging. Ital so high light show damaging a very strong dollar can be for global growth.

In particular it highlights the limited effect of global QE efforts. Over the last year, the ECB and BoJ have added about USD850bn to their reserves. The relative increase in ECB and BoJ stimulus may have exaggerated the decline in global growth due to the shift in exchange rates. However, these lower exchange rates have so far not produced sufficiently large export growth numbers to offset the wider growth story. Also, it illustrates that the EM implication of global USD growth is only marginally negative despite significant declines in real exchange rates. The key takeaway here though as far as we are concerned is that QE policies have not generated more value than they have destroyed. It is also worth noting that this dollar recession is worse than the 2001 recession by some margin.

Leave A Comment