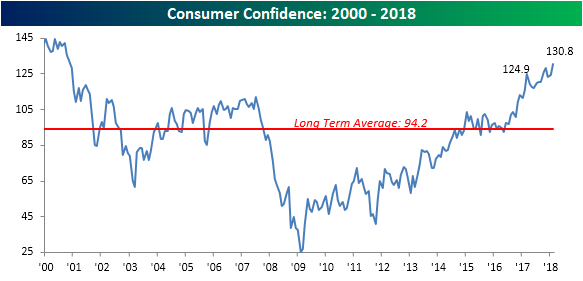

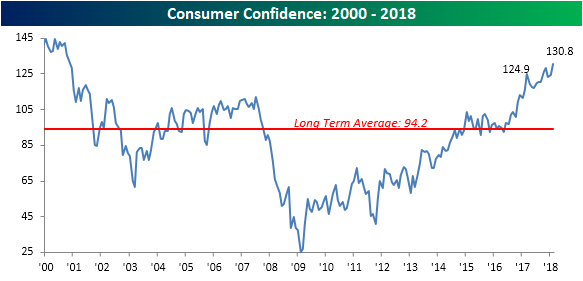

Tuesday morning’s report on Consumer Confidence for February handily topped already positive expectations, as the headline index came in at 130.8 (versus expectations for 126.0), which was the highest level since November 2000. While Consumer Confidence had a hard time getting above its long-term average for much of the current expansion, it has now been above that level of 94.2 for 21 straight months.

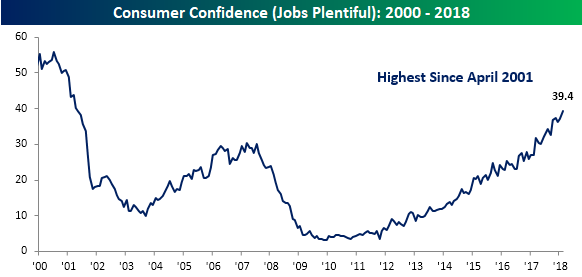

One area of the economy where consumers are very confident is in the employment picture. More and more lately, the percentage of consumers who consider jobs as being ‘plentiful’ has been on the rise. In February’s report, it came in just under 40%, which was the highest level since April 2001. It only makes sense that consumers who are confident also think jobs are easy to get.

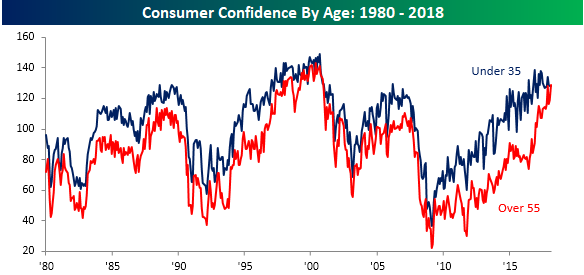

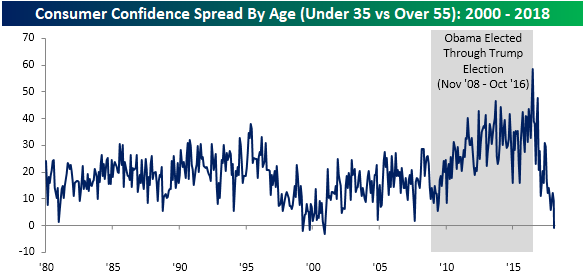

One of the more interesting trends in confidence since the November 2016 election is the shifting demographics of confidence levels. In a nutshell, younger consumers (under 35) have seen little in the way of a confidence boost since President Trump was elected, while older consumers (over 55) have seen confidence surge. After the generational divide between the two age groups widened considerably during the early to mid part of the expansion, confidence levels are now roughly equal.

Looking at how the spread between the two has changed over time, you can actually see that as of the most recent report, confidence among older consumers is actually higher than it is for younger consumers. This type of confidence inversion is so rare in fact that it has only occurred three other times since 1980, and all of them came in 1999 and 2000. Another interesting trend to notice is that throughout the terms of President Obama, the confidence gap between younger and older consumers steadily rose. Right after President Trump was elected, however, that gap was quickly erased. You know where to find the President’s base!

While politics has a lot to do with the shift in confidence among different age groups, another factor is interest rates.President Obama’s tenure also coincided with a period when interest rates were generally at or very close to zero, and the impact of low-interest rates has nearly the exact opposite impact on older Americans, who generally have more savings than it does on younger Americans, who usually have more debt. When you think about it that way, it makes a lot more sense that confidence among older Americans started to improve after interest rates bottomed.

Leave A Comment