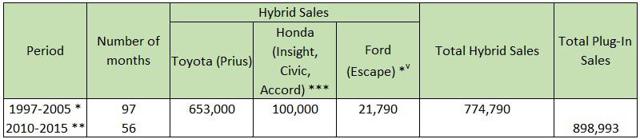

It should be clear by now that EVs are winning against conventional hybrids in their respective initial years of adoption. As we can see in an updated version of a table I published in 2014, in their initial 97 months of introduction, 774,790 hybrids were sold, whereas in only 57 months of adoption, 898,993 plug-ins were retailed (See Table 1). In essence, what this means is that plug-ins are in fact being adopted at a much faster pace than conventional hybrids. Still, in July 2015, Toyota (NYSE:TM) announced it had crossed the 8 million hybrid mark while plug-ins would have recently reached the one-million global plug-in sales milestone only.

Table 1

World: Hybrid and Plug-In Comparable Sales Since Their Launching

Sources: For hybrid sales:

,

, and

. For plug-in sales:

,

, and

.

*December 1997-December 2005.

**December 2010-July 2015.

***Number corresponds to period November 1999-April 2005.

*v Number corresponds to 2004 and 2005.

At first sight, this ample margin in favor of Toyota would give the impression that its future with hybrids is bright. However, the Japanese giant automaker has at this juncture at least two reasons to worry. For one thing, there appears to be some evidence that Toyota Prius sales are beginning to “lose their charge” (See Figure 1). For another, plug-in sales seem to be growing exponentially (See Figure 2) which may conspire against Toyota’s efforts to position its newest fuel cell electric vehicle model (i.e. the Mirai) in the market.

Figure 1

Source: Cleantechnica.com

Figure 2

Source: Ev-sales.blogspot.com

In this article, I take up the first issue mentioned above only, leaving the second one for a forthcoming contribution. Just as the rise of Toyota hybrid sales since 1997 were mostly related to a hike in oil prices, the recent decline now seems to be linked to dipping fossil fuel values. To the extent that the current falling oil prices are likely to be a permanent rather than a conjectural phenomenon, they could eventually drive down Toyota hybrid sales even further. But can this apparent positive correlation between Toyota hybrids and oil prices be thought of as a positive causal connection between these two variables as well?

In what follows, I will intend to show that there’s a causal mechanism running from oil prices to Toyota’s hybrid sales. But, before I do that, let me describe the extent of the positive correlation between the two variables. In Table 2, the correlation matrix of Toyota hybrid sales in Europe, Japan, North America, other countries, and in the world (GLOBAL), and WTI and Brent oil prices is presented. In all cases, correlations between Toyota hybrid sales and oil prices are high and positive. Please note that correlations among Toyota hybrids sales themselves in different parts of the world and globally are also high and positive.

Table 2

Correlation Matrix Between Oil Prices and Toyota’s Hybrids

Sources: Toyota and EIA

But can these results hold up to a causal association between Toyota hybrid sales and oil prices? For reasons of space and time, I will restrict my analysis now to one fundamental relationship: That between Toyota global hybrid sales (GLOBAL) and WTI oil prices (WTI) (See Figure 3).

Figure 3

Evolution of GLOBAL and WTI

1997-2014

Source: Toyota and EIA

In accordance with standard econometric practice, it appears reasonable to proceed as follows: First, test for stationarity of the two variables in their level form (i.e. own values) to find their order of integration. Second, check for cointegration between hybrid sales and oil prices. Third, test for unidirectional Granger causality running from WTI oil prices to Toyota’s global hybrid sales.

Stationarity

To see if the variables are stationary, we need to test for unit roots. The whole issue about testing for unit roots arose when econometricians discovered that many macroeconomic variables are non-stationary, because they can be described as a “random walk” (i.e. a process where the current value of a variable is composed of the past value plus an error term defined as a white noise (a normal variable with zero mean and variance one)) even after a deterministic trend is removed. It then became apparent that running regressions with that kind of data could lead to misleading values of R2, Durbin-Watson and t statistics.

Leave A Comment