George A. Romero knew how to make an entrance onto the Hollywood stage.

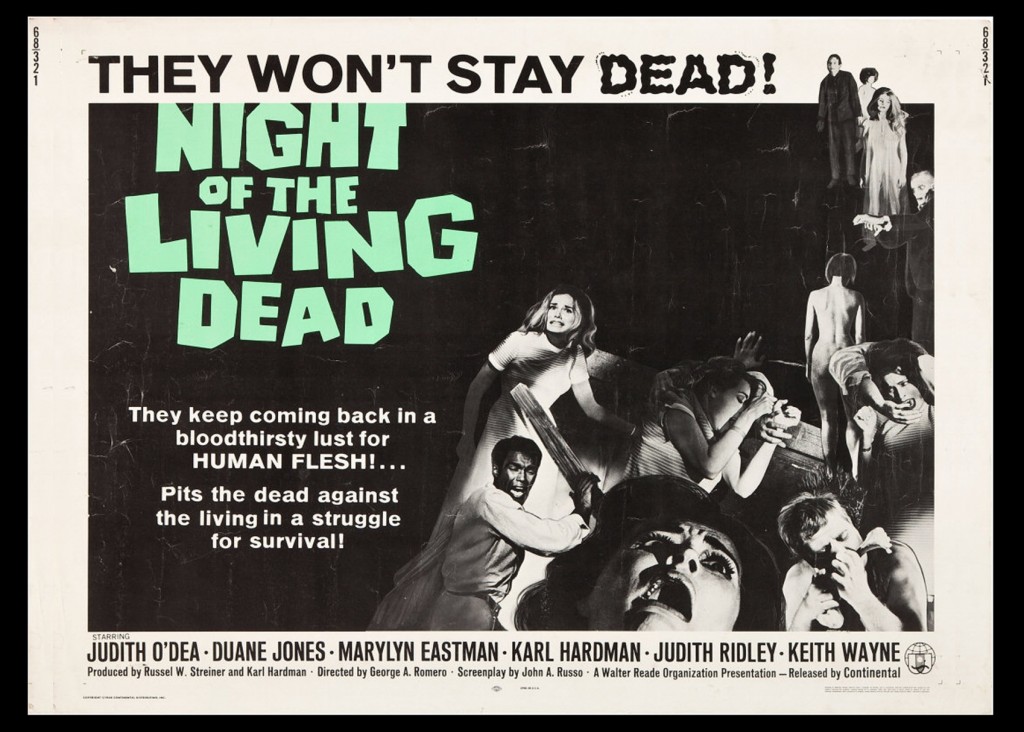

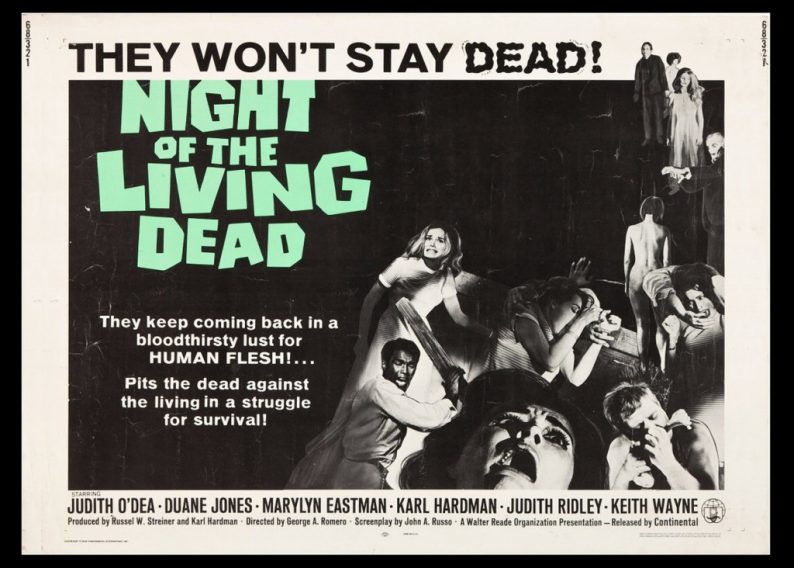

Night of the Living Dead, his 1968 directorial debut, set the ‘A’ standard for horror flicks. Though the special effects may seem unsophisticated to today’s moviegoers, the movie still terrifies modern day audiences.

The premise of the film has stood the test of time and been the subject of numerous sequels: The recently deceased find no peace in their graveyard slumber; they rise from the dead hungry to feast upon living human flesh. The film, produced on a shoestring budget of $114,000, follows a group of seven unlucky souls trapped in a rural Pennsylvania farmhouse, desperate to escape the fate that has befallen others who’ve succumbed to the grasp of the ravenous zombies.

It’s plausible that Romero had come across the work of Joseph Schumpeter before entering filmmaking. The phrase ‘creative destruction’ was coined by the Austrian American economist in 1942 and refers to what W. Michael Cox describes as “free market’s messy way of delivering progress.” Something new and innovative necessarily kills off the methodology it replaces, freeing an economic pathway to advancement. The absence of creative destruction, therefore, invites zombie industries to languish, feeding off healthy and more efficient new entrants and dragging down economic growth.

Think Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, which removed seeds from cotton in a fraction of the time it had taken to do so by hand. Imagine a world before the rise of railroads, in which horse drawn wagons were primarily responsible for transporting goods. Dare we go there? Close your eyes and picture what it would take to get through any given day with a rotary phone.

Feeling immeasurably more productive with that iPhone in hand? Then you understand creative destruction, what Schumpeter himself called, “The essential fact about capitalism.”

I suppose that makes quantitative easing and other central banking magic tricks like negative interest rates the essential executioner of capitalism. Look no further than the amount of U.S. industrial capacity that is up and running, or better put, fallow. At 76.5 percent, the rate of capacity utilization remains 3.6 percentage points below its average dating back to 1972.

A friendly reminder – the U.S. economy is technically 80 months into ‘recovery.’ Imagine how much better off we’d be if a little creative destruction would have been allowed to take hold.

Leave A Comment