It has been said that the economy is one dog with two owners, the government and the central bank. The problem for the dog is which one has the best treats and which one has the leash.

In the last 10 years it’s been the FOMC to lean on, now it’s the US President. For markets, it’s the balancing of bonds against stocks.The cost of money matters as it sets the value of future cash flows, puts a number on growth potential and solves for the base case for profits. We had a one dog market last week as the bond market rout drove down equity prices, put fear in credit and lifted the USD back higher despite doubts about the US trade and fiscal policy.

US 10-year yields touched 3.25% back to 2011 highs. If the last week brought expectations for US economic outperformance with unemployment at 39-year lows and Services ISM at a record, then the next week brings a return of China/US trade worries and US C/A doubts with a $230 billion deluge of debt sales. The dogged equation of higher real growth means higher real rates hits globally.

The reality check next week will be US CPI along with more reactions from Fed speakers. Rates are the dog that wag the tail of the economy after the bone of price increases change the business cycle. Whether the Fed is ahead or behind the curve becomes the likely new obsession which won’t mix well with the threat of a prolonged trade war with China, rising doubts about EU politics and jitters about higher energy prices into winter. The problem in the week and month ahead may be best described by the removal of the central banker’s accommodative policy that intrinsically supports risk-taking.

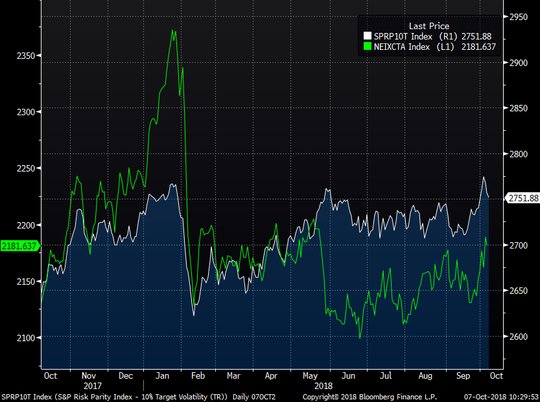

The chart of returns (from Bloomberg using SocGen CTA index and the S&P Risk Parity 10% vol for risk-parity programs) makes this clear with the January turnaround fully reversed into October but recently and perhaps most troublingly, unwinding last week. There is no Powell S&P 500 put. As for the CTA models in markets, the run-up in oil, USD and rates has helped trend followers regain some ground but they remain well off the January highs. Perhaps the only safe bet is that volatility will follow as systematic approaches to trading face a Fed less inclined to trust their models.

What Happened over the Weekend?

Kavanaugh wins a seat on the US Supreme Court, China PBOC cuts the reserve ratio for the fourth time this year, Brazil elections start with 147 million choosing their next leader, elections also being held in Bosnia and Cameroon along with a referendum on same-sex marriage in Romania. US Secretary of State Pompeo and North Korea Leader Kim agree to a second US-North Korea summit as soon as possible.

Risk of 3.60 in BRL after election

Question for the Week Ahead: Did QE and negative interest rates work?

Ten years after Lehman and investors are still concerned about a liquidity trap. The US FOMC, by removing its accommodation and unwinding the balance sheet bloated by bond buying, is the exception, not the rule for global central banks. The next year will be a crucial test of whether QE and negative rates can be unwound without a divisive crisis. he success in the US and other QE policy has been clouded by the rise of populist policies – some of which have been blamed on the plans intent to inflate risky assets. While this all sounds logical, the success of such policy in keeping people working and economies growing shouldn’t be lost and the costs of doing nothing would have led to much more painful politics. The IMF released its reckoning of the policies 10 years on and its required reading for all investors fearful of its removal.

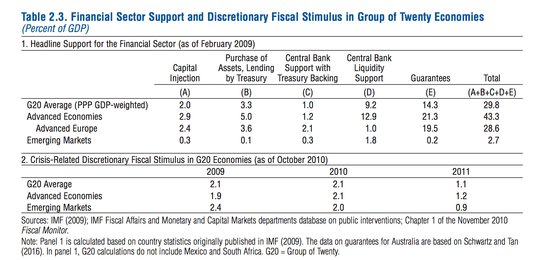

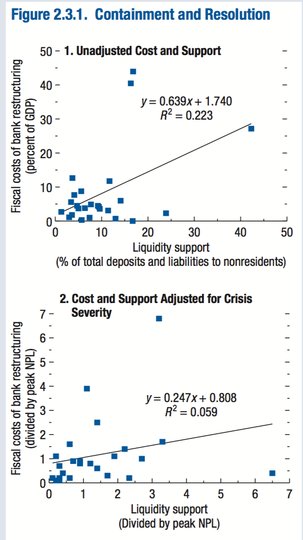

The crisis resolution included fiscal spending – notably in China and other EM – and bank bailouts – notably in EU and US. The relationship of global banks to supporting EM changed after the crisis and that remains a significant question about trade and growth. The rise of China and its belt-road initiative and lending to frontier and EM nations followed. Many would suggest that a China slowdown induced by a prolonged US trade war will continue to hamper EM recoveries regardless of their FX devaluations.

The lessons for the next crisis maybe about fixing the banks faster as the chapter spells out. The logical responses for China and perhaps India in the months ahead could be important to their own present shocks.

Leave A Comment