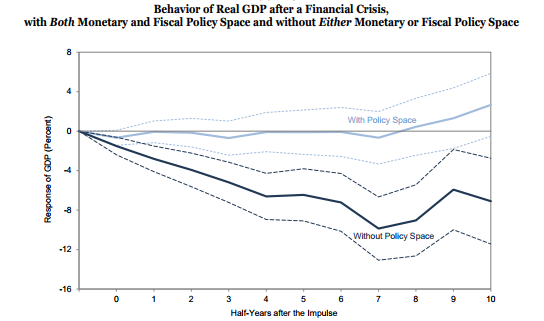

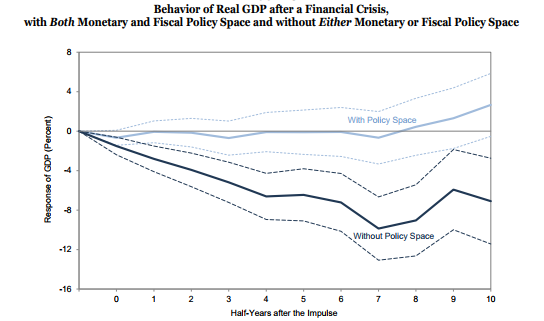

“Countries that faced financial distress with substantial amounts of both monetary and fiscal policy space on average experienced output declines of less than 1 percent, while those that faced distress with neither type of space experienced average declines of almost 10 percent.” (Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, Why Some Times Are Different: Macroeconomic Policy and the Aftermath of Financial Crises, NBER Digest, Jan. 2018)

A NBER empirical study found what most economists have always understood. Countries facing economic or financial crises are better able to deal with them if the authorities have policy room to stimulate their economy using both monetary and fiscal policy measures.

As well, their historical review indicated that countries with adequate policy room tend to recover more quickly from an economic crisis than the counterpart countries which had little policy room to manoeuvre. The above conclusion, which seems so obvious, was based on the post-crisis economic performances of 24 advanced economies since 1967.

Policy room on the monetary side depends upon how high-interest rates are before the crisis hits, while policy room on the fiscal side depends upon a countries debt to GDP ratio. That is, countries with low debt to GDP ratios typically have more room to use an aggressive fiscal policy to offset the economic downturn. In other words, based on these criteria, a country like Canada should have plenty of monetary and fiscal policy room to battle the next economic downturn.

The following chart, which was extracted from their report, shows the typical change in real GDP which occurs for countries with and without policy room.

Leave A Comment