This article examines a somewhat over-looked, but important, discussion that raged among academic researchers in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. The topic: factors versus characteristics.

What do you mean, “Factors versus characteristics?”

We often highlight that the value premium can be explained by either risk and/or mispricing. A core aspect of the risk argument is that a portfolio’s factor “loading,” or covariance, on a specific factor (e.g., Fama and French HML value factor) represent a proxy for some unobserved systematic risk. The characteristics argument claims that value firms earned a higher expected return simply because they have higher B/M ratios (which may be independent of systematic risk).

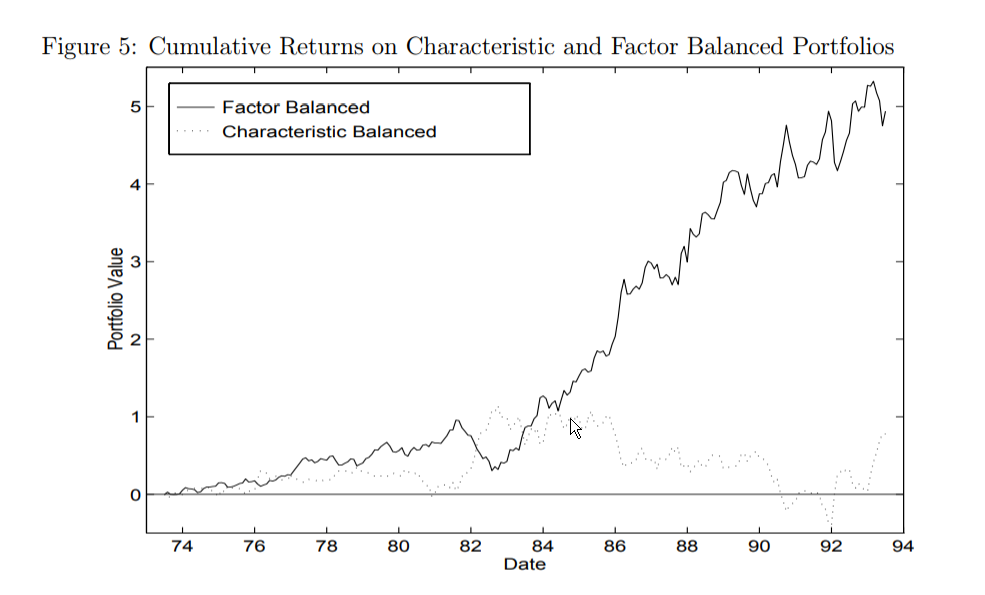

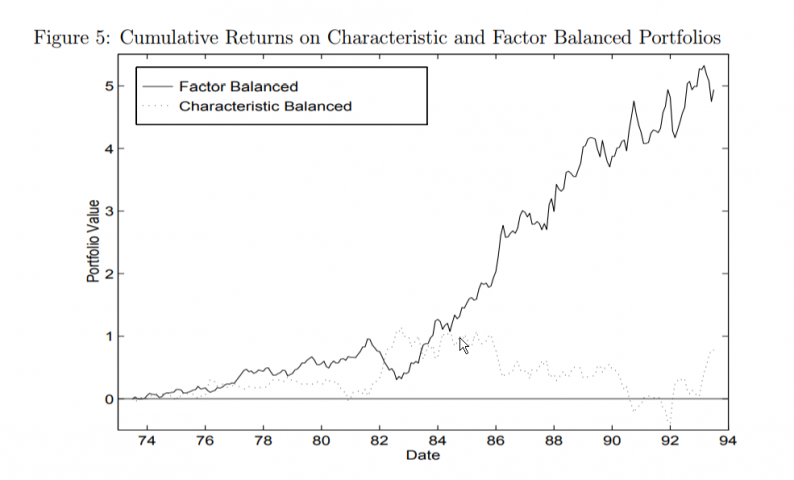

The evidence from the primary set of papers (here and here) under discussion strongly suggests that investors should focus on characteristics, not factors:

As we’ll show, the debate is arguably not as clear as the chart above seems to suggest, and academics have continued to argue over the interpretation of the value premium for almost 25 years now. Why? The argument driving the value premium underlies core arguments related to how markets work — a fundamental question we still don’t completely understand.

A summary of each argument is described below:(1)

So what’s the answer? A new paper entitled, “Interpreting Factor Models,” says it best:

We argue that tests of reduced-form factor models and horse races between “characteristics” and “covariances’” cannot discriminate between alternative models of investor beliefs.

In short, nobody really knows.

We would argue that there is a mix of all three ideas going on at the same time. As more investors learn about an investment approach that previously had higher returns (value investing), the expected returns to that approach may diminish in the future (implication of the characteristic theory), if arbitrage constraints are minimal. (6)

The rest of the article is broken into three sections:

Let’s dig into the debate on factors or characteristics.

Do Portfolio Factors or Characteristics Drive Expected Returns?

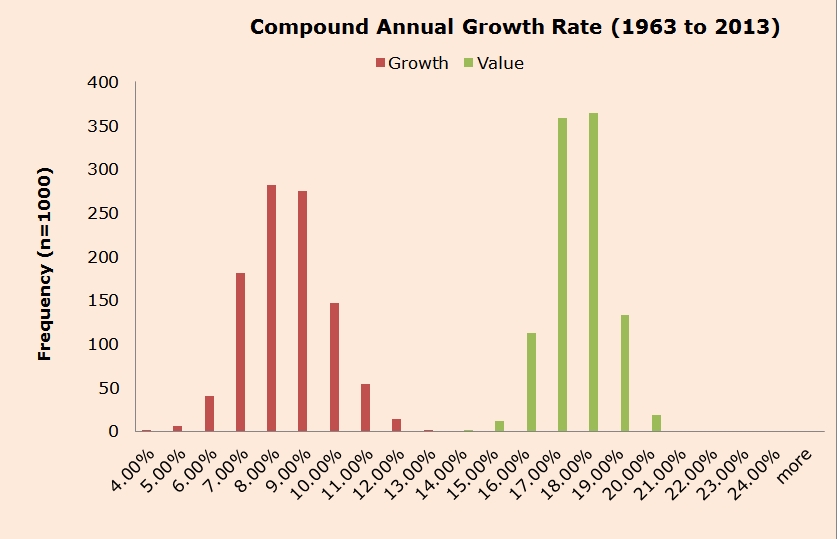

Most in finance are aware of the value premium: Historically, cheap stocks have outperformed expensive stocks (based on some price to fundamental). Below is a chart from a value premium:which highlights the performance of cheap vs. expensive portfolio simulations from 1963 to 2013.

One of the original papers on the value premium topic was Fama and French in 1993. In their paper, they find that there are three factors (the market, size, and value proxied by Mkt_rf, SMB, and HML) that explain the cross-section of stock returns. More important to this discussion, they suggest that value is a risk factor, as value firms covary with one another. In their story, the covariance matters, and is why the loading on HML is important.(7)

But what are some implications of this theory? Directly from FF 1993:

The regression slopes and the historical average premiums for the factors can then be used to estimate the (unconditional) expected return for the portfolio.

In other words, the HML loading can be used to estimate future expected returns. A higher loading implies a higher amount of risk, which implies a higher rate of expected return. This is exactly the type of interpretation we often hear from DFA advisors, many of whom have been taught by Fama and French.

But the factor approach (and the reliance on regression slopes to make decisions) is not a panacea and has plenty of holes like any other approach.

We have discussed in detail, an alternative explanation to risk being the driver of the value premium is the LSV behavioral theory. The LSV theory suggests that investors over extrapolate data, causing prices to sometimes deviate from fundamentals and limits to arbitrage prevent these mispricings from being “arbitraged” away.

It is important, for this discussion, to note that the argument between the risk and LSV behavior camps does not focus on whether or not the return premia of value and small firms can be explained by a factor model–they agree it can. However, they argue whether the factors represent an economically relevant risk or mispricing that is costly to exploit.

However, there is a 3rd explanation for the value premium, which is also a “mispricing” based argument–the premium is simply driven by characteristics (not covariances, or factors). In other words, your HML loading does NOT matter, but your portfolio book-to-market ratio does matter.

Why Characteristics Matter: The Theory

This theory was proposed by Kent Daniel and Sheridan Titman in 1997, in their heretitled “Evidence on the Characteristics of Cross Sectional Variation in Stock Returns.”(8)(9) This is a well-written paper. The introduction very clearly states what the paper will test, and what they find:

In contrast, this article addresses the more fundamental question of whether the return patterns of characteristic-sorted portfolios are really consistent with a factor model at all. Specifically, we ask (1) whether there really are pervasive factors that are directly associated with size and book-to-market; and (2) whether there are risk premia associated with these factors. In other words, we directly test whether the high returns of high book-to-market and small size stocks can be attributed to their factor loadings.

Our results indicate that (1) there is no discernible separate risk factor associated with high or low book-to-market (characteristic) firms, and (2) there is no return premium associated with any of the three factors identified by Fama and French (1993), suggesting that the high returns related to these portfolios cannot be viewed as compensation for factor risk…

Once we control for firm characteristics, expected returns do not appear to be positively related to the loadings on the market, HML, or SMB factors.

So what this paper is trying to argue is that after controlling for characteristics, factor exposures (i.e., factor “loadings”) don’t tell us much about expected returns. In other words, if an investor is calculating “HML loadings” as a means to tell them something about future returns, they should stop this practice. Instead, investors should identify the book-to-market ratio of their portfolio, which will be much more predictive of expected returns.

Leave A Comment