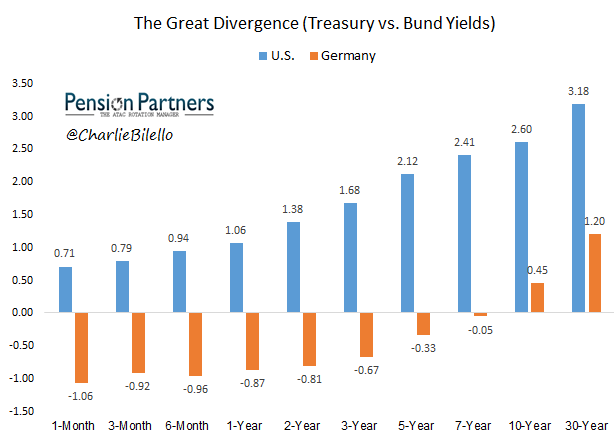

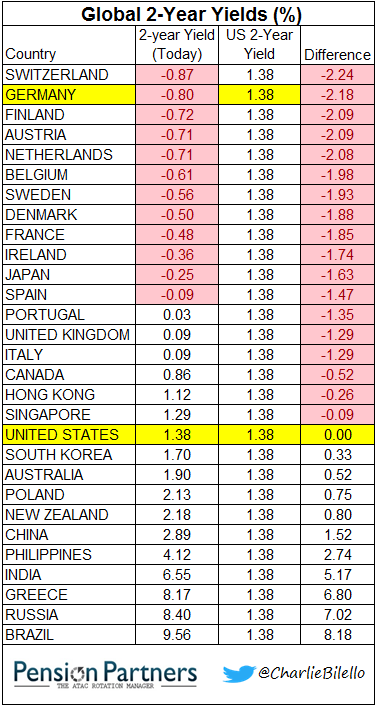

The most interesting thing in markets today is the growing divergence in short-term interest rates between the U.S. and the rest of the developed world.

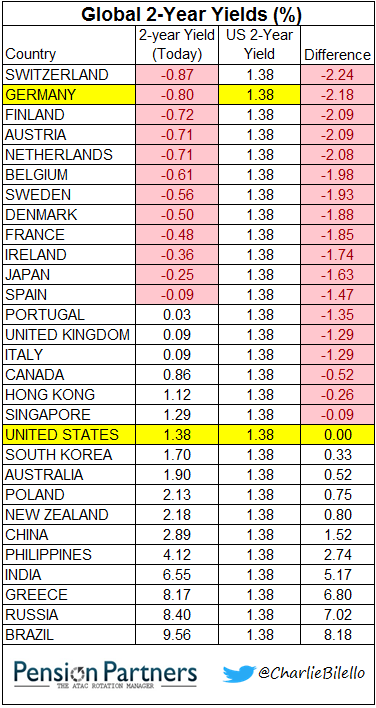

While Japan and most of Europe have negative 2-year yields, the U.S. 2-year Treasury yield has moved all the way up to 1.38%, its highest level since 2009.

At 0.71%, the U.S. 1-month Treasury bill has a higher yield than 10-year German bunds (0.45%).

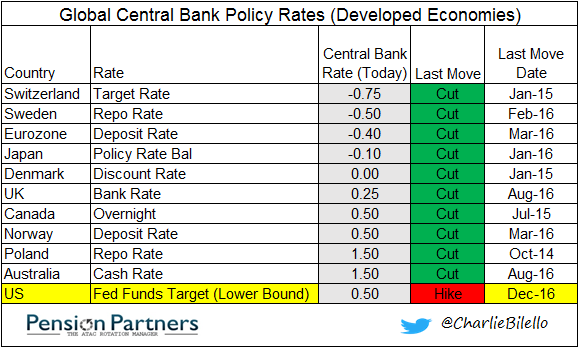

What accounts for this massive differential? Central Bank policy, with the U.S. being the only developed country in the world in a tightening cycle. This week the Fed is expected to raise interest rates for the third time since December 2015. In stark contrast, the Bank of Japan (BOJ), Bank of England (BOE), and European Central Bank (ECB) have all cut rates since December 2015.

In viewing the above tables, three questions come to mind:

1) Is the divergence justified?

2) Is the divergence sustainable?

3) Will the BOJ/BOE/ECB move toward the Fed or will the Fed move toward the rest of the world?

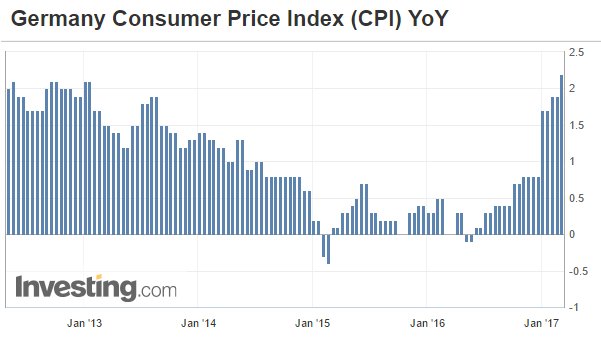

On the first question, the only way to justify the divergence is if U.S. growth/inflation were rising while global growth/inflation were falling. This does not seem to be the case.

Germany, the largest economy in Europe, recently reported CPI of 2.2%, its highest level in years. This is not much below the U.S. rate of 2.5%. Overall, CPI in Europe is 2.0% over the past year, far from a deflationary environment.

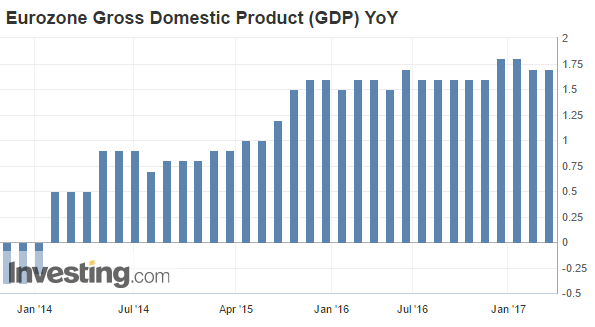

On the subject of growth, Eurozone real GDP of 1.7% is only 0.2% below the recent reading in the United States of 1.9%.

On the basis of growth and inflation, the divergence does not seem justified. Why, then, are the ECB and BOJ pursuing negative interest rate policies? Because they want to suppress the value of their currencies against the dollar. And suppress they have, which undoubtedly has been helpful in terms of Manufacturing, with Eurozone Manufacturing PMI hitting a 70-month high and Japanese Manufacturing PMI hitting a 35-month high.

Leave A Comment