The call for minimizing the onrushing downdraft has continued, particularly in the wake of yesterday’s huge disappointment in the ISM. Where the “12%” figure had slowly entered the mainstream lexicon before, it has fast become fully incorporated into any article’s template. There are hardly any pieces about the curious manufacturing recession that don’t mention it, as it has evolved into economists’ shorthand for “nothing to see here”:

With manufacturing accounting for only 12 percent of the economy, analysts say it is unlikely the persistent weakness will deter the Federal Reserve from raising interest rates this month.

“Manufacturing is being pummeled by the stronger dollar and the weakness of global demand, but the other 88 percent of the economy continues to perform well. This won’t prevent the Fed from raising interest rates at the mid-December meeting,” said Steve Murphy, a U.S. economist at Capital Economics in Toronto.

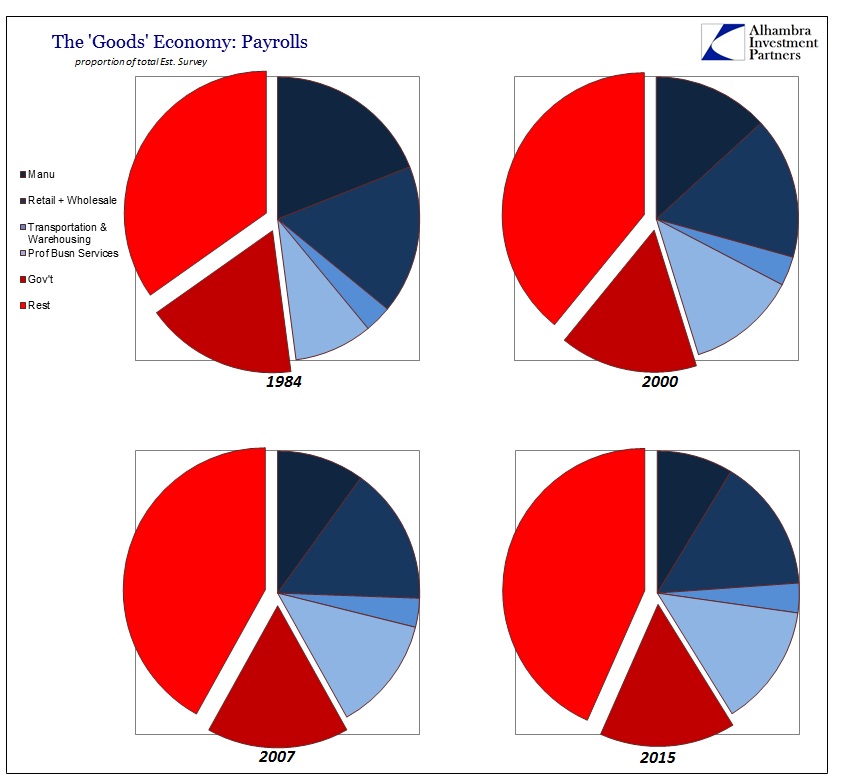

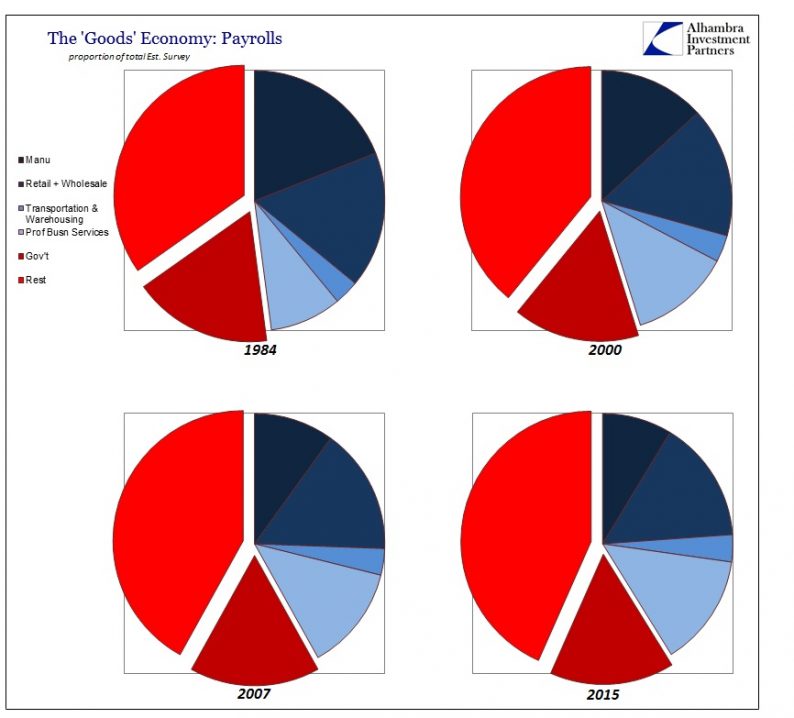

It’s an intentional fallacy, of sorts, because manufacturing isn’t the end of the process. If we are strictly speaking of the “goods economy”, the 12% is woefully under counting. There is a whole range of activity that precedes manufacturing (relevant, of course, to commodity prices) and even more that follows. Raw material has to get out of the ground and then all of it, whatever stage of processing, needs to move around; several times. Beyond that lies the heart of this “recovery”, the retail jobs that have become the synthesis and staple of monetary redistribution in the cracked financial age.

As noted previously, the number of jobs devoted to some element of the goods economy is almost exactly in the same proportion now as it was in 2007 just before the Great Recession started – in the goods economy.

While most economists remain steadfast in working backwards from “next year”, it is incredibly important to note that this, too, is changing. Citigroup’s strategists and economists have completely “evolved” in their expectations, and not just for China.

Leave A Comment