The FOMC at least still knows how to throw a party. It may not be what it once was, but for one day there was the familiar euphoria predicated upon the wish that central bankers might know something about anything. All-too-quickly, however, it vanished as it becomes increasingly clear, despite all attempts to rewrite this history, that there are no answers. After but a day, reality rudely intruded on the recovery, perhaps suggesting that it was the simultaneous recession announcement people are now more attuned to.

U.S. stocks dropped Thursday on persistent concern over faltering global economic growth, led by declines in energy and materials shares, a day after shares had rallied on the Federal Reserve’s decision to raise interest rates.

The selloff continues so far this morning as global, for once, means global which includes the US much to the dismay of the mainstream that still clings to the idea that the US economy is in primary condition for overheating. The dichotomy remains simply how it defined QE’s influence; “stimulus” is assumed to be stimulative, so at the end of it the intended target must have been stimulated even when it doesn’t show it. Therefore, according to orthodox mythology, if that isn’t truly apparent it only means it is about to be.

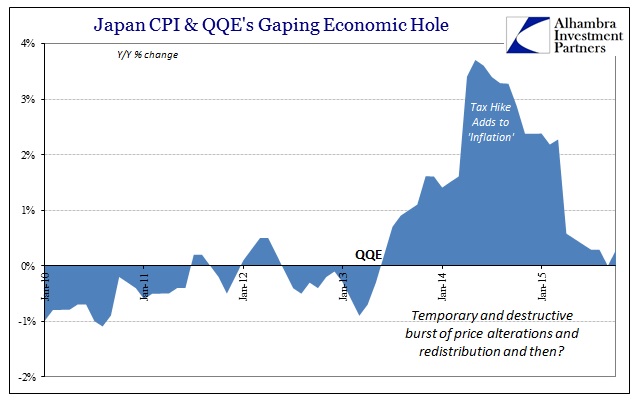

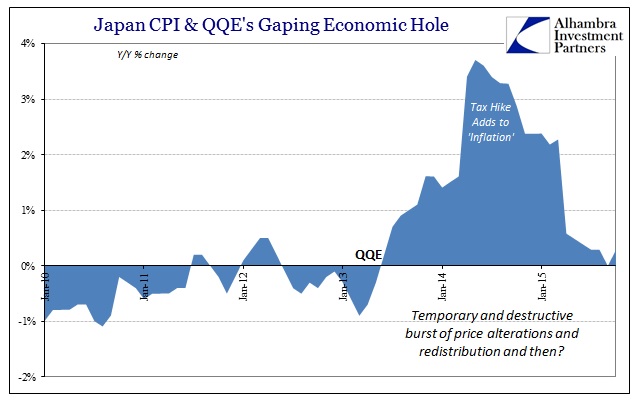

In Japan, however, this mysticism is contrarily naked. Redistribution and “inflation” suggestions are revealed in all their gruesome horror. The Bank of Japan has no plausible outlet for “overheating” since the entire Japanese economy is a gaping wound; Japanese households most especially. Further, as to leave little doubt about any of it, that hole in the Japanese economy coincides exactly with what the Bank of Japan infuriatingly claims will heal it.

As QQE has had an obvious influence on the yen, and thus consumer prices more directly than what the Fed can influence and conjure, there is yet no “pump priming” effects visible anywhere, only clear devastation. Both Japanese Household Income and Japanese Household Spending, real and nominal, are declining again. That’s an undesirable outcome all its own, but given the huge declines in 2014, renewed contraction is evidence of monetary cancer.

Leave A Comment