On July 21, 2009, then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke wrote an op-edpublished in the Wall Street Journal seeking to allay any fears over balance sheet expansion. This was all relatively new, and at that time the recovery seemed a good bet and appeared to be underway in many places. Bernanke’s goal was to soothe any fears that “inflation” would get out of control because of the FOMC’s actions in QE1 and other expansionary programs.

But as the economy recovers, banks should find more opportunities to lend out their reserves. That would produce faster growth in broad money (for example, M1 or M2) and easier credit conditions, which could ultimately result in inflationary pressures—unless we adopt countervailing policy measures. When the time comes to tighten monetary policy, we must either eliminate these large reserve balances or, if they remain, neutralize any potential undesired effects on the economy.

He argued that though he increased the “money supply” his efforts alone at the point of full recovery which he would determine would be enough to forestall any out of control price spiral. Undoubtedly his reasoning for writing this article at that moment was sound, namely that his biggest (loudest) critics were those arguing that he was trading one worst case for another; perhaps to the point, as some charged, of hyperinflationary collapse. What he put forth to defray those arguments was, however, nonsense.

We know that without fail because of what he said above – is Janet Yellen in any way considering that the Fed “must…eliminate these large reserve balances?” Not at all, in fact the settled “wisdom” of the FOMC right now is that even in the current thrust of “exit” (which the Fed can’t even get to in a straight line) the Fed’s balance sheet must at least remain constant.

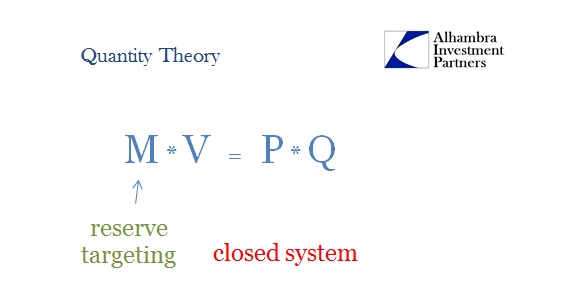

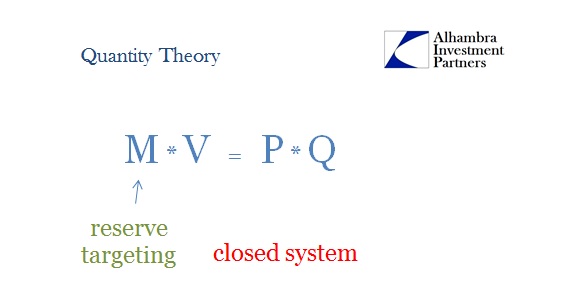

At issue is really the core of all problems. What exactly are these bank reserves? In July 2009, Bernanke was treating them as any good standing monetarist would, as if they were money even HPM (high powered money) as Milton Friedman once described. Even though the financial system had undergone a radical (shadow) transformation, the monetarists still held fast to the belief that bank reserves, and by extension the Federal Reserve, were at its center. Control lies at that point – in theory.

In November 2006, Chairman Bernanke spoke to the ECB’s Fourth Annual Central Banking Conference in Frankfurt, Germany. Given how events have transpired, what he said that day doesn’t seem to immediately fit with overall monetary policy and policy philosophy. For the Fed, policy has been very simple even though money has increasingly taken the opposite approach.

For example, in the mid-1970s, just when the FOMC began to specify money growth targets, econometric estimates of M1 money demand relationships began to break down, predicting faster money growth than was actually observed. This breakdown–dubbed “the case of the missing money” by Princeton economist Stephen Goldfeld (1976)–significantly complicated the selection of appropriate targets for money growth. Similar problems arose in the early 1980s–the period of the Volcker experiment–when the introduction of new types of bank accounts again made M1 money demand difficult to predict. Attempts to find stable relationships between M1 growth and growth in other nominal quantities were unsuccessful, and formal growth rate targets for M1 were discontinued in 1987.

Leave A Comment