Deutsche Bank wasn’t the only global institution under the gun of the US Justice Department. While the German bank settled for a record fine earlier this year, RBS was also hit. Theirs was an eye-popping $4.9 billion settlement. The ostensibly British bank had already set aside $3.4 billion for the anticipated civil penalty, meaning that only $1.4 billion (and change) would hit Q2 2018 earnings.

Shares in the bank rose sharply on the news.

It’s hard to generate the same level of outrage as ten years ago. Maybe that’s the point. In the smoldering aftermath of global dollar panic, it was easy to cast villains. Everyone wanted one and Wall Street provided plenty.

Not so much anymore. Stocks are at record highs, so fewer people seem to care about the excesses of such a long-ago age. As part of the DOJ investigation, thousands of RBS emails of housing bubble vintage were subpoenaed, and are now a matter for public record in the wake of the settlement.

They are every bit as salacious as you might expect. The BSD’s from the eighties may have been long gone, the mystique remained behind anyway. The big stuff isn’t stocks, it’s always FICC. The head trader at RBS received a call from a friend just after things got serious:

[I’m] sure your parents never imagine[d] they’d raise a son who [would] destroy the housing market in the richest nation on the planet.

Egos run big in FICC, as big as their portfolios. The unidentified RBS scoundrel modestly replied, “I take exception to the word ‘destroy.’ I am more comfortable with ‘severely damage”.

And so it has been written. It was “toxic waste” and a culture out of control that nearly killed the system. That’s wrong on both counts; it was never really about subprime nor those who took advantage of it, but how things got that way in the first place. And the massive expansion that brought all this upon us didn’t nearly kill the system, as this last decade has proven.

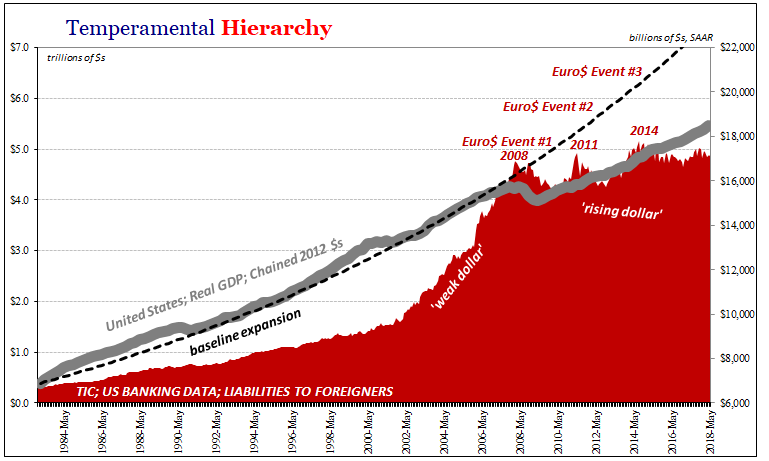

The eurodollar era was one of riskless return. There wasn’t anything anyone could dream up that wouldn’t make someone money. There wasn’t any bank, no matter how previously stodgy, that wouldn’t bend every standard to do it. Expansion was the name of the game, no matter how you built the bottom line.

These are not new problems. They are, in fact, the same kinds of questions that informally humans have been asking themselves about since before written history. So long as there has been money there has been the temptation to conjure it on demand. What’s unusual about the last half-century is who was doing the conjuring.

It wasn’t central bankers and governments, for once, though the latter appreciated the monetary and financial space to have become overtly reckless (along with housing market participants), while the former were very eager to take credit for all the economic “moderation” it seemed to generate.

In June 1990, Milton Friedman wrote for National Review Magazine:

From time immemorial, money has existed, and, from time immemorial, it has been connected with a commodity, though the specific commodity has varied widely. From time to time, individual countries have cut the link and adopted fiat currencies, but almost always as a temporary response to a crisis, such as war, never as a permanent system. Of such episodes, Irving Fisher wrote in 1911, “irredeemable paper money has almost invariably proved a curse to the country employing it.”

Leave A Comment