A cacophony of recession chatter is filling the airwaves. Some experts are already declaring we are in one while others are raising warning flags. Their message has not been lost on the masses: Google searches for the word “recession” have risen to the highest level since 2012. Interestingly, many commentators cite the 20% decline in global stock prices as the warning signal, if not the cause. But veteran investor Joe McAlinden believes the U.S. economy will continue to expand in the year ahead.

Recognition that the U.S. economy is not falling into recession, however, may not be a market panacea, as good news on the economy could be bad news for stocks. Investors who have completely priced out Federal Reserve rate hikes for this year will soon refocus on the next potential market disrupter: Those Fed hikes may get priced back in.

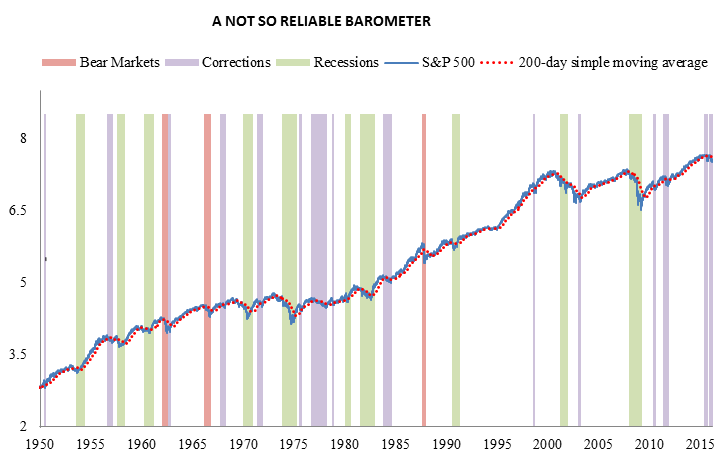

Over the decades, I have seen investors mistakenly look at the stock market as a foolproof barometer of overall economic health. To be fair, share prices do typically fall preceding a recession and rise prior to an expansion. But the stock market as an economic barometer has given almost as many false signals as right ones. Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson sardonically sniped in 1966 that market indexes had “predicted nine out of the last five recessions! And its mistakes were beauties.” Samuelson points out a rather obvious notion: though market indices can often retreat significantly, such declines don’t necessarily signal an economic recession—a fact exemplified in the 1987 market crash.

At MRP, we believe we are right in the midst of one of those “real beauties”—a big drop, NOT followed by a recession. There is no denying that the world has been in a dramatic flux since commodities have plummeted, particularly in critical emerging economies, like China, which has experienced big contractions in growth rates, and Brazil which is falling into a depression. The pain is felt sharpest in commodity exporting countries. Also, business investment (capex and inventories) has been cut back throughout the world—including the U.S., although the latest durable goods orders suggest a firming may be underway.

Leave A Comment