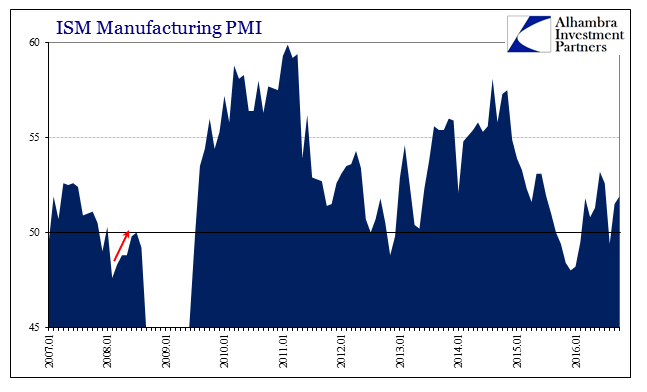

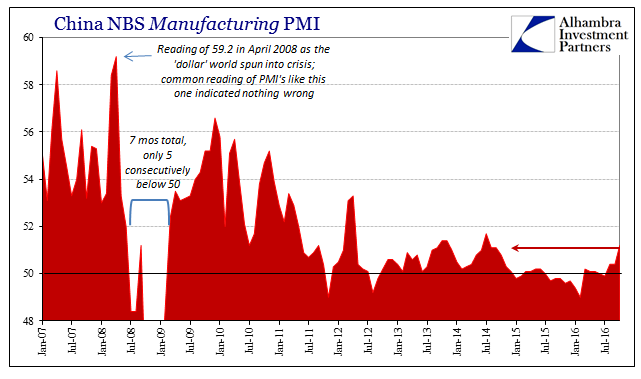

A strong cohort of global PMI’s has cheered today pretty much everyone, from economists to the media and anyone else in between. China’s official Manufacturing PMI was calculated at 51.2 in October, the highest level since July 2014, up seemingly significantly from the 49.9 just three months ago this July. In the United States, the ISM Manufacturing rose again to 51.9 from 51.5 last month, but that registers two months of what are being interpreted as solidifying gains after the August “scare” where the index dropped just below 50.

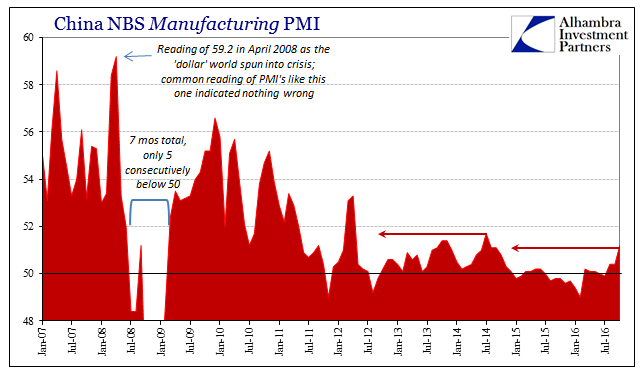

Again, the world sees these numbers as an improvement when instead they show, pretty conclusively, nothing has changed. The global economy is still stuck in depression, but these statistics demonstrate what has become typical, that there are times during all this when “experts” feel a little better about it. PMI’s capture sentiment and that is what washes out into these numbers.

The problem is as I have been writing for months, that there is great difficulty in translating these indices or any economic accounts into actually meaningful explanations. The mainstream in being wed to the business cycle filters all this data through that paradigm – and ends up confused. There is indeed cycles at work here; just not the business cycle.

This idea should be acknowledged in widespread fashion simply because it is exceedingly easy to see. Starting with China’s Manufacturing PMI, though at a multi-year high in October 2016 it only recalls the last multi-year high. In July 2014, the index jumped to 51.7, which at the time was the highest level in more than two years before it dating back to early 2012. And then, as now, it was treated as conclusive proof that prior weakness had been skillfully put to the past. In other words, the index has only repeated itself.

These non-business cycles, perhaps better classified as depression cycles, are as much reaction in expectations and emotions to a misunderstanding of these points. They play out in narratives as well as actual economic activity. It all starts with central banks and official “stimulus” policies that for a time appear to be effective. The combination of belief in them as well as the natural economic tendency for growth to be better after an “event” achieves a high degree of acceptance.

Leave A Comment