Ten years after the Lehman bankruptcy, the financial elite is obsessed with what will send the world spiraling into the next financial crisis. And with household debt relatively tame by historical standards (excluding student loans, which however will likely be forgiven at some point in the future), mortgage debt nowhere near the relative levels of 2007, the most likely catalyst to emerge is corporate debt. Indeed, in a NYT op-ed penned by Morgan Stanley’s, Ruchir Sharma, the bank’s chief global strategist made the claim that “when the American markets start feeling it, the results are likely be very different from 2008 — corporate meltdowns rather than mortgage defaults, and bond and pension funds affected before big investment banks.”

But what would be the trigger for said corporate meltdown?

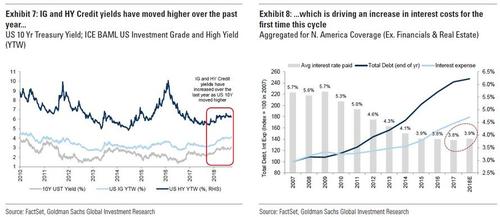

According to a new report from Goldman Sachs, the most likely precipitating factor would be rising interest rates which after the next major round of debt rollovers over the next several years in an environment of rising rates would push corporate cash flows low enough that debt can no longer be serviced effectively.

While low rates in the past decade have been a boon to capital markets, pushing yield-starved investors into stocks, a dangerous side-effect of this decade of rate repression has been companies eagerly taking advantage of low rates to more than double their debt levels since 2007. And, like many homeowners, companies have also been able to take advantage of lower borrowing rates to drive their average interest costs lower each year this cycle…. until now.

According to Goldman, based on the company’s forecasts, 2018 is likely to be the first year that the average interest expense is expected to tick higher, even if modestly.

There is one major consequence of this transition: interest expenses will flip from a tailwind for EPS growth to a headwind on a go-forward basis and in some cases will create a risk to guidance. As shown in the chart below, in aggregate, total interest has increased over the course of this cycle, though it has largely lagged the overall increase in debt levels.

The silver lining of the debt bubble created by central banks since the global financial crisis, is that along with refinancing at lower rates, companies have been able to generally extend maturities in recent years at attractive rates given investors search for yield as well as a gradual flattening of the yield curve.

According to Goldman’s calculations, the average maturity of new issuance in recent years has averaged between 15-17 years, up from 11-13 years earlier this cycle and <10 years for most of the late 1990’s and early 2000’s.

And while this has pushed back the day when rates catch up to the overall increase in debt, as is typically the case, there is nonetheless a substantial amount of debt coming due over the next few years: according to the bank’s estimates there is over $1.3 trillion of debt for our non-financials coverage maturing through 2020, roughly 20% of the total debt outstanding.

Leave A Comment