Hedge funds talk big about returns.

Historically, successful managers have claimed credit for the favorable risk/return profiles of their funds, touting skilled security selection and portfolio management as a competitive edge. But the advent of investible benchmarks for a number of hedge fund strategies prove there’s more than just skill involved.

Hedge fund returns can be broken down into two components:

What most managers describe is alpha. So, why don’t they more talk about — and capture — hedge fund beta?

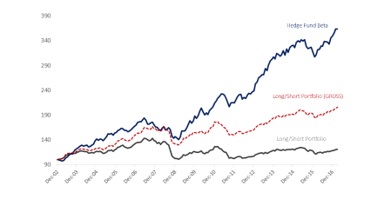

Here’s an example. Consider an investable index of long/short equity beta, represented here by the BRI Long/Short Equity (BRILSE) Index, to compare against a dynamic portfolio of long/short equity funds to quantify the cost of hedge fund ownership in dollars.

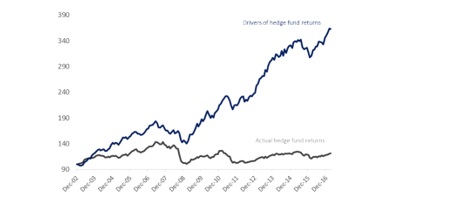

During the last 15 years period, the hedge fund portfolio clearly has not kept pace with the actual, underlying, returns of hedge funds as captured by the BRILSE Index:

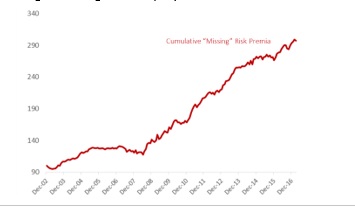

Looking at just the cumulative differential in performance between the investable hedge fund index and the actual portfolio of hedge funds, we can get an idea of the cumulative risk premia that should have been passed to investors through the long/short equity funds – but wasn’t:

What’s most apparent about this is how steadily the spread grows. That’s in part due to fees, sure, but even still, the erosion of value over time is remarkably consistent. In fact, the fees account for less than half of the performance difference over time:

If you can’t blame the market and you can’t blame fees, then who can you blame?

After the financial crisis, one of the largest value propositions of active hedge fund managers was their ability to dynamically shift fund exposure to exploit market swings. Overtrading and poor timing decisions in trying to meet that proposition for investors might be a likely explanation for the continuation of the spread.

Leave A Comment