Hungary isn’t known today as one of the world’s top gold producing countries. There was a time, though, when it accounted for around three-quarters of Europe’s entire output of the yellow metal if you can believe it. According to historian Peter Sugar’s A History of Hungary, the central European country was a “veritable El Dorado” in the 14th century, and its gold pieces circulated widely across the entire continent, competing with those minted in Italy and England.

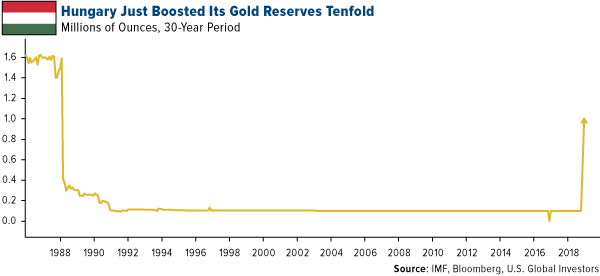

It was this rich mining heritage that Hungary’s central bank evoked when it announced last week its decision to increase gold holdings tenfold, from 3.1 metric tons to 31.5 tons, taking gold’s share of total reserves to 4.4 percent. (Gold accounts for 73.5 percent of U.S. reserves, by comparison, the most of any country.) Hungarian central bank governor Gyorgy Matolcsy described the move as one of “economic and national strategic importance,” adding that the extra gold made the country’s reserves “safer” and “reduced risk.” This is the first time since 1986 that Hungary has increased its gold holdings.

The country isn’t alone in its mission to diversify. This month we also learned that Poland became the first European Union (EU) member to increase its gold reserves in two decades. The Eastern European country added as much as 9 metric tons of hard assets between July and August of this year. Central banks in Russia, Turkey, and Kazakhstan have also kept up their gold buying, representing close to 90 percent of the activity we’ve seen this year.

Meanwhile, the EU has continued to print paper money.

A Good Store of Value

So why should banks—or investors, for that matter—be interested in boosting their gold holdings? One reason is timing. Until recently, gold prices have been relatively affordable, trading at 52-week lows of around $1,180 an ounce in mid-August and at the end of September. Central banks’ investment was wisely made. From those lows, gold is now up more than 4 percent on stock volatility.

Leave A Comment