Managers of public companies are under constant pressure to meet quarterly guidance and maximize profits, often at the expense of future profitability. Those pressures, driven by a number of factors, are likely to increase in the next 10 to 15 years as corporate profits decline and labor costs rise. Public companies are dying faster than ever, and these contracting corporate life spans are, on average, diminishing long-term value creation, making it more important than ever that business leaders act to ensure that the drive for short-term performance doesn’t come at the expense of sustainable value creation. Along with board members and investors, business leaders should review their companies’ governance structures and consider whether any changes could better serve their long-term prospects.

What is driving short-term behavior?

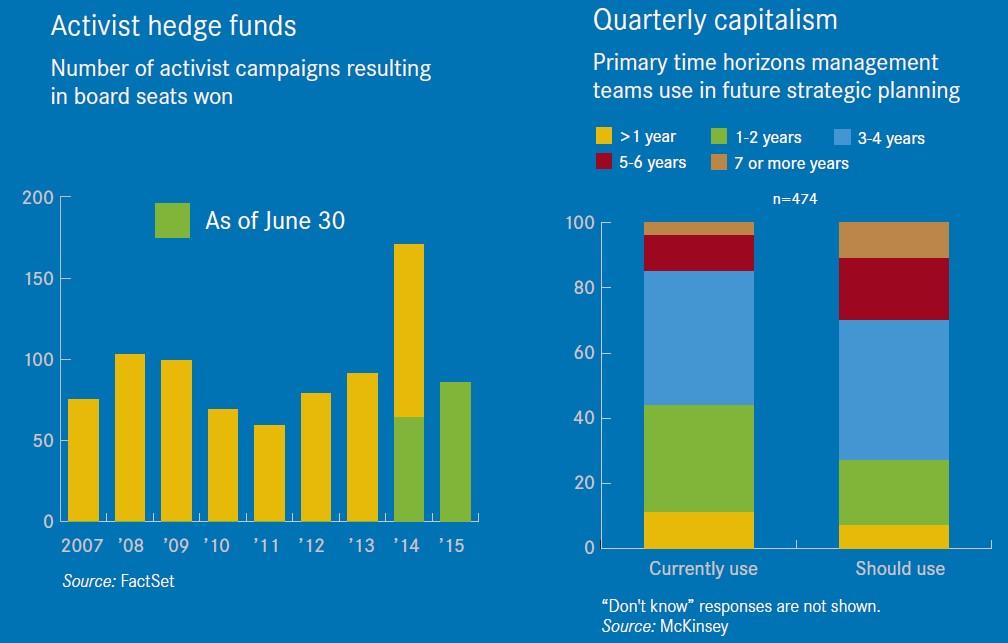

Activist hedge funds: Activist investors are gaining ground in the governance of public companies. In 2014, activists gained board seats at 107 companies, an all-time record that is likely to be broken this year. And, when companies resisted putting activists on their boards, the activists won proxy contests 73 percent of the time last year.

Increasing payouts to shareholders is one of the most frequent demands of activist hedge funds, after obtaining board seats and M&A campaigns such as sale of the company or a spin-off, and these demands drive some short-term behavior. From October 2008 through August 15, 2015, hedge fund activists led more than 220 public campaigns against US companies to increase payouts to shareholders.

Executive compensation design: The design of stock compensation, the main component of executive pay, may exacerbate that focus on short-term results. Performance triggers for stock compensation that are tied to near-term indicators, such as earnings per share or one-year share price increases, encourage executives to focus more on short-term share price and accounting measures than on long-term performance. Stock compensation is also linked to increasing stock buyback programs at companies that seek to offset dilution to shareholders when options are exercised or share grants vest. Whether buybacks add or destroy value depends upon the price paid relative to intrinsic value. If a company pays less than intrinsic value (i.e., shares are cheap), a buyback will add value. If the company pays more than intrinsic value (i.e., shares are expensive) a buyback will destroy value, since wealth is transferred from those who hold to those who sold.

Leave A Comment