On January 24, Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin either misspoke or let slip a Freudian sort of wish. Extolling a weak rather than strong dollar, it was seemingly a total break from longstanding official US policy. It’s not really a policy anyone takes too seriously, if for no other reason than the dollar isn’t really a part of the Treasury.

Still, the comments moved markets and led to all the usual hysteria, including of the recent inflation variety. Behind the Treasury Secretary’s comments was an unofficial acknowledgment – when the dollar falls in exchange value, the economy seems to do much better. Even if officials can’t really figure out why the appeal of this correlation is obvious.

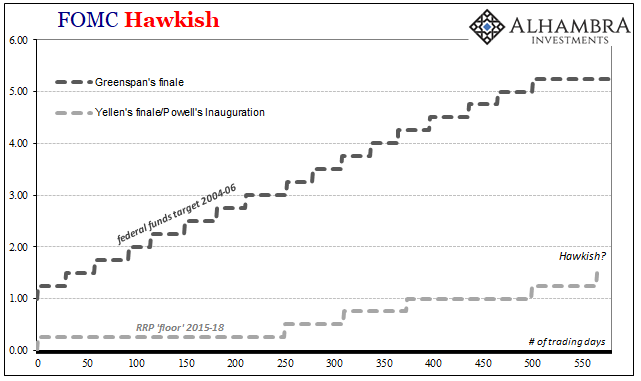

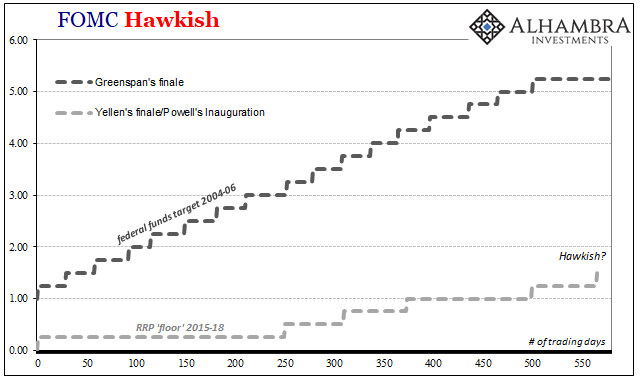

Jerome Powell just concluded his first “rate hike”, meaning that each of the last three Federal Reserve Chairmen have all contributed to the same exit process. Begun as tapering under Bernanke, QE was ended under Yellen who then began the “rate hike” progression. It will continue for the time being under Powell, though the markets aren’t as sure as he sounds about how it will end.

Whatever the future case, this past history is shameful. How can an exit process last through three Chairman across the span of just about five years and counting? You might get the sense that the economy isn’t so great and that policymakers really don’t know what they are doing. Greenspan was no better when it came to money and bonds, but he completed 17 hikes in two years.

If you are somewhat lost especially when the unemployment rate is no help and you can’t figure out inflation, what might you anchor to in order to at least try and plot a plausible policy path?

The FOMC models give us a big clue. Since the middle of last year, FOMC estimates for 2018 and 2019 GDP have been raised. The latest projections released today show that for this year at least the Fed is more optimistic about the intermediate outlook than it has been in some time.

Leave A Comment