File it under “what were they thinking?” In March 2015, confronted by a severe external monetary squeeze, the PBOC made a truly radical choice. Maybe it was that for a few months anyway things looked a little better. The eurodollar system had practically melted down globally first on October 15, 2014 (collateral) and then in December 2014 and January 2015 culminating with the breaking of the Swiss National Bank. February and March 2015 were so much better by comparison.

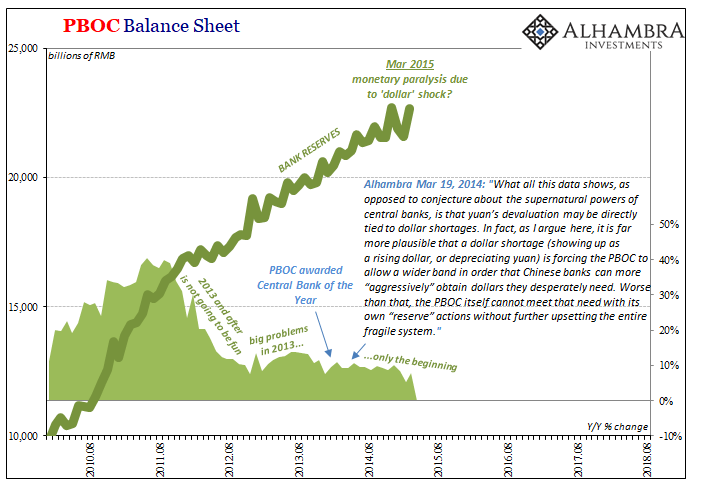

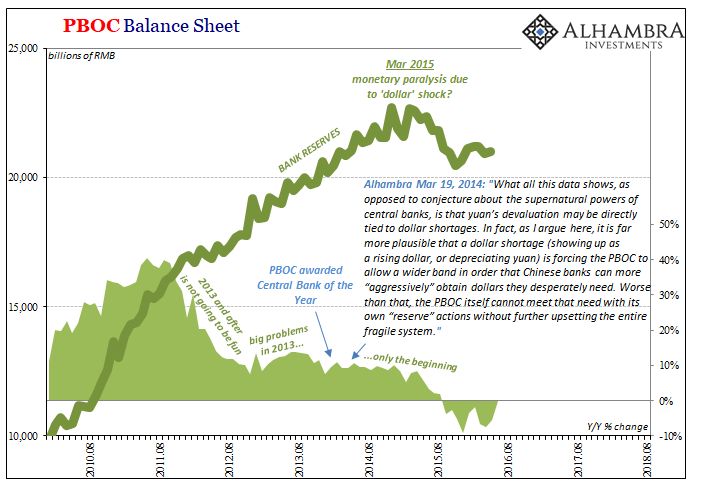

Perhaps thinking that was the beginning of a recovery, at least an end to the squeeze, China’s central bank would decide beginning at that time over the rest of the year it would permit its asset side contraction (eurodollar problem) to visit domestically via its liability side. As I diagrammed earlier today, on the money side the level of bank reserves had to correspond proportionally. They shrunk precipitously.

Obviously, Chinese officials underestimated what that would mean. They would have had to have believed their offsetting tool, RRR cuts, were going to be a more than sufficient cushion to what they were attempting. They were wrong. Very wrong.

In theory, it is pretty simple and straightforward: less dollars for China means at least slowing growth or in this case contraction on the asset side of the central bank balance sheet; that can mean either increasing RMB assets (bank window lending through the MLF and other new programs) or letting base money decline (which is what they chose); decreasing bank reserves would therefore be offset by allowing banks to use more of those they have already accumulated (RRR cut).

Undoubtedly, the central bank did all the proper calculations and ran all the orthodox Monte Carlo simulations such that in March 2015 central bankers were confident enough it would work. Initially, it did.

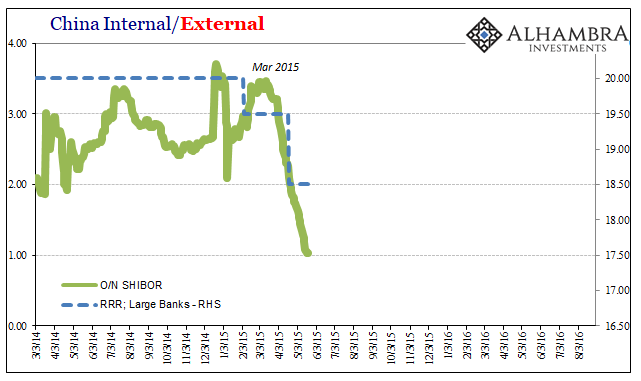

Despite what became a sharp fall in bank reserves, 150 bps between two RRR cuts seemed to have left RMB money markets with a flood of RMB liquidity (pushing SHIBOR, unsecured RMB money rates, decidedly lower). These were aided by reductions in benchmark money rates, too, the so-called “double shots” of Chinese monetary policy.

Leave A Comment