In 1993, Stanford economist John B. Taylor wrote an influential paper that introduced the economics profession (statisticians, almost all) to what was later called the Taylor Rule. The need for such a “rule” was an unspoken outgrowth of monetary evolution. In the 1960’s and 1970’s long-established regression models estimating the influence of then-defined money on economic variables had broken down almost completely.

It left central banks of the 1980’s to essentially discretionary monetary policy in total, a situation that no reasonable official or economist at the time wished to see put into practice. In the interest of some kind of limitation, Taylor drew in several economic variables (aggregates) that could in theory tell the Fed what to do with its primary policy lever – whatever that lever might be.

The preferred policy rules that have emerged from this research have not generally involved fixed settings for the instruments of monetary policy, such as a constant growth rate for the money supply. The rules are responsive, calling for changes in the money supply, the monetary base, or the short-term interest rate in response to changes in the price level or real income.

It is interesting that in the original piece Taylor’s so-called rule isn’t actually meant exclusively for interest rate targeting but over the years has been adapted that way not on the same econometric principles but on the legend of Alan Greenspan’s tenure. It introduces another element of subjectivity that blurs the very monetary evolution motivating it as a factor.

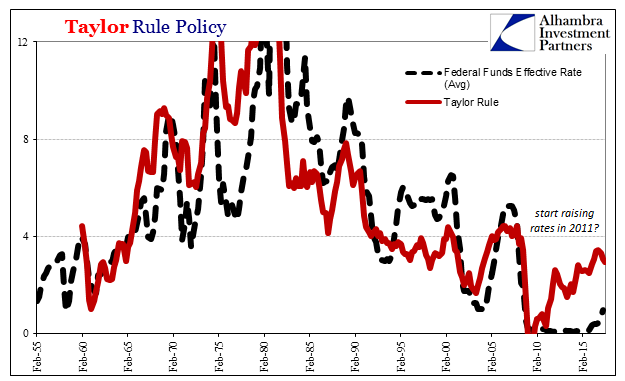

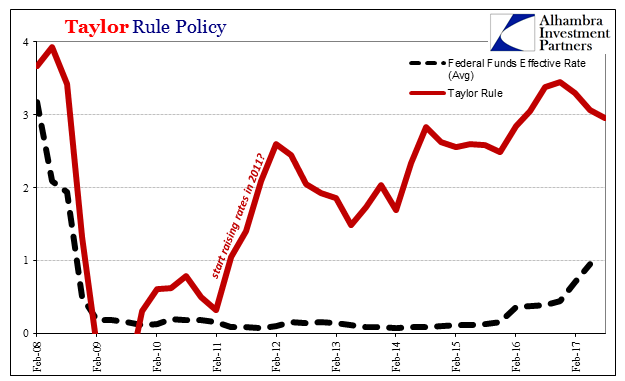

There are, of course, different versions nowadays, with modified Taylor Rules springing up with some frequency. A full part of the reason for that is what you see on the right hand side of the chart immediately above. There has never been a perfect fit one to the other (Taylor prescription for federal funds and the actual rate), but in recent years the distance has grown quite large and triggering an often intense orthodox debate.

It is in many ways the mirror of (illegitimate) Fed criticism in the early crisis period. Then it was QE was so much money printing it risked igniting inflation, if not hyperinflation. Now it is the Fed is so far behind the curve that it risks igniting inflation, if not runaway inflation. They were and are both wrong for reasons of both money (modern) and its effects on the economy.

Leave A Comment