As the fourth round of NAFTA negotiations comes to an end, the agreement’s survival has once again been brought into question. US President Donald Trump has threatened to strike a new deal with just Canada. Mexico downplayed the threat, saying it would walk away from negotiations if the new terms brought by the US put it at a disadvantage. For their part, the Canadians have been quiet, keeping their cards much closer to their chests.

All this commotion belies the fact that no NAFTA member is likely to walk away from the deal. The economic realities and commercial interests that led to its formation in the first place still incentivize cooperation, no matter how much any side postures.

An Apparent Advantage

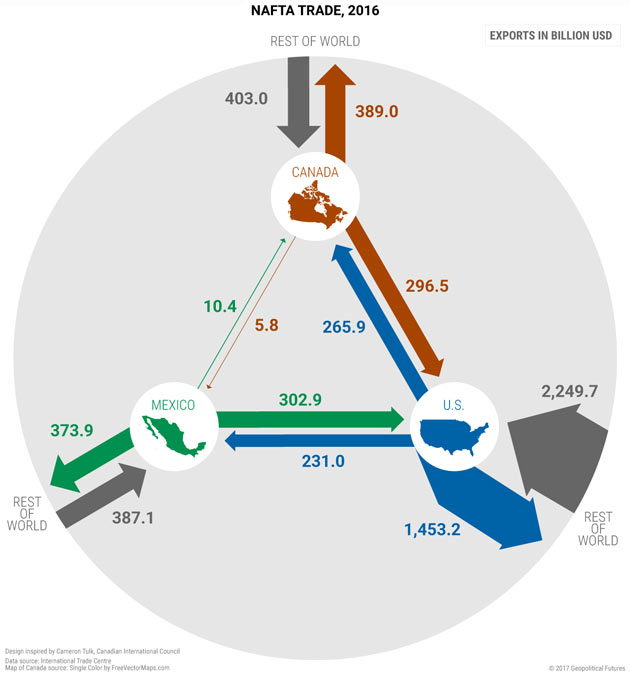

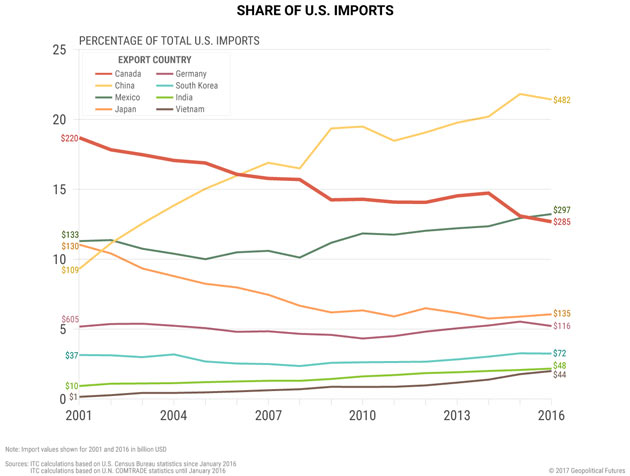

Still, at first the glance, the United States appears to have the upper hand. It boasts the largest economy in the world and accounts for about a quarter of global gross domestic product. Exports account for only roughly 12% of its GDP, according to the Department of Commerce, so the US has the benefit of a strong consumer class to boost economic activity when international demand is low. Easy access to such a large and vibrant consumer market has enabled Mexico and Canada to build up their economies without having to trade much with each other. In Mexico, on the other hand, exports account for about 38% of GDP, and about 81% of those go straight to the United States. Exports account for 31% of Canada’s GDP, according to the World Bank, about 76% of which go to the US. Exports are simply more important to the Canadian and Mexican economies than they are to the US’s.

In keeping with this apparent advantage, there are a few areas in which the United States could hurt Mexico if Washington decided to restrict trade or impose tariffs. These include gasoline, steel, agriculture, and automobiles. Though Mexico produces crude oil, it relies on imports for most of its refined gasoline. Last year, according to Pemex, Mexico imported 62% of its gasoline, mostly from the US. Mexico is a net consumer of steel, importing about 40% of it from the US. (By comparison, the US sells just 4% of its steel to Mexico.) Mexico relies on the US for 85% of its total soybean supply and almost exclusively on the US for corn—a staple of the Mexican diet—accounting for a third of the country’s total supply. In automobile production, Mexico and the US have very integrated supply chains such that either one has the potential to disrupt the other.

Leave A Comment