A friend of mine recently said that intellectual honesty often requires imagining the worst. Of course, in the study of climate change and natural resources one needs only to read the analyses of scientists to imagine the worst.

Imagining the worst in not necessarily the same as believing the worst is inevitable or even likely. It can be merely a standard part of both scenario and emergency planning. Of course, imagining the worst can also be a double-edged sword with a sinister edge, sometimes eliciting Richard Hofstadter’s paranoid style of politics.

When we imagine the worst concerning our political opponents or our enemies (sadly often placed into the same category), this is merely a reflex designed to justify our own hatreds and also a tool for broadly smearing those with whom we disagree. Clearly, this is not the same as seeking out solid evidence and using logic to construct a worst-case scenario.

In scenario planning the whole point is to consider seriously a range of possible outcomes and formulate plans for dealing with those outcomes. For example, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reference case for world oil production (defined as crude oil and lease condensate) shows it rising from about 76 million barrels per day (mbpd) in 2012 to 99.5 mbpd in 2040. The low production case is 92 mbpd and the high production case is almost 103 mbpd.

You may feel that this range doesn’t reflect more extreme scenarios, but at least the agency offers a range. Some forecasters pretend to know to the second decimal point the future of oil production and reserves decades hence. It’s hard to put this down to anything but hubris.

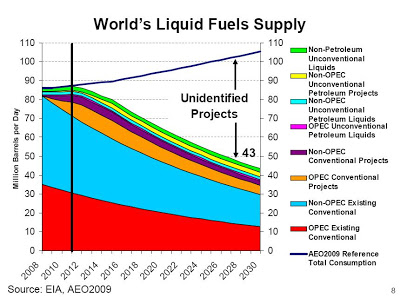

Compare these forecasts to a forecast based on much sounder data, this one made by an EIA researcher in 2009 about how much oil we would have to find and deliver to meet rather extravagant future demand expectations:

The researcher demonstrated that we will have to find more than five new Saudi Arabias by the early 2030’s (or 2040’s if demand growth slows somewhat as the EIA anticipates) if we are going to fill the gap between production from existing fields and expected future demand (in this case for so-called total liquids which include natural gas plant liquids and other non-oil items). He based this on the estimated average production decline rate of 4 percent per year for existing fields, a fairly conservative number given that other estimates range as high as 6 to 9 percent. We know with a fair degree of accuracy what existing fields will on average be producing decades hence because we have a long series of actual field data.

Leave A Comment