With the Fed having hiked thrice and calling for three more hikes still, the 2017 Hoisington First Quarter Review contains a call that will have many if not most analysts shaking their heads: “The secular low in bond yields remains in

the future, not the past,” says Lacy Hunt.

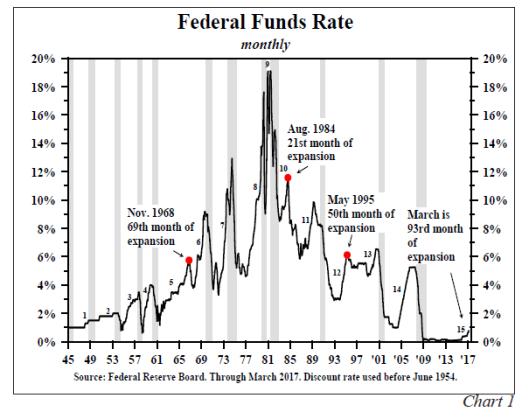

The Federal Reserve has initiated the fifteenth tightening cycle since 1945 (Chart 1). Conspicuously, in 80% of the prior fourteen episodes, recessions followed, with outright business contractions being avoided in just three cases. What is notable today is that the economy is in the 93rd month of this expansion, a length of time that is well beyond periods in prior expansions where soft landings occurred (1968, 1984 and 1995). This is relevant because the pent-up demand from the prior downturn has been exhausted; thus, the economy is extremely vulnerable to a shock, which could lead to recession. Regardless of whether there was an associated recession, the last ten cycles of tightening all triggered financial crises.

Total domestic nonfinancial debt, excluding off balance sheet liabilities such as leases and unfunded pension liabilities, surged to a record 254.8% of GDP in 2016, 5.6% greater than in 2009 when Lehman Brothers failed (Chart 2). Total debt, which includes domestic nonfinancial, foreign and bank debt, amounted to 372.5% of GDP in 2016, compared with 251.9% of GDP in 2006, the final year of previous tightening cycle, which, in turn, was greater than in any earlier time from 1870 through 2006. The situation in the business sector deserves particular scrutiny. Business debt surged to a record 72.6% of GDP in 2016, for the first time eclipsing the prior peak of 70.2% reached in 2009. With the business sector so levered, not much room for miscalculation exists. As such, the risk is clearly present that the Fed’s restraint will chase out one or more heavily leveraged players, just as was the case in all the previous tightening cycles since the 1960s.

Academic studies reflect that economic growth slows with over-indebtedness. Thus a powerful negative headwind is reinforcing

the present monetary tightening.

In the last three months, no growth was registered in total loans and nonfinancial commercial paper. Historically, the three-month growth has not been this weak until the economy is already in recession.

In the first quarter survey of senior bank lending officers, almost 10% of the banks were tightening standards for both credit card and other consumer type loans. This was almost identical to the percentage when the economy entered the 2000 and 2008 recessions. Standards for commercial real estate loans have also been raised and in the first quarter were just below the levels when the economy entered the last two recessions.

In summary, monetary restraint is taking hold in all the different ways of measuring the Fed’s actions in a late stage expansion where historically the final result was either a recession, a financial crisis or both.

Our economic view for 2017 remains unchanged. We continue to anticipate no more than 2% growth in nominal GDP for the full calendar year. The risks, however, are to the downside.

The downturn in nominal GDP growth suggests that a rise in inflation to above 2% will be rejected and that by year end the inflation rate will be considerably slower. In such an economic environment long-term Treasury yields should continue to work irregularly lower over the balance of the year.

Our view on bond yields does not change if the Fed further boosts the federal funds rate this year. Any additional increases will place further

downward pressure on the reserve, monetary and credit aggregates as well as tighten bank lending standards. Such actions will not allow the

economy to regain the economic momentum that was lost in 2016 and in the early part of this year.

Thus, the secular low in bond yields remains in the future, not the past.

Van R. Hoisington

Lacy H. Hunt, Ph.D.

Leave A Comment