A rising tide lifts all boats, does it not? That cliché of economic policy is meant to highlight the ways in which economic growth, as a substitute for targeted social policies, can make life better not just for the privileged, but for the disadvantaged, as well. However, the cliché is misleading in that the causation is not all one way. A better social safety net can contribute to a stronger economy and faster growth of both actual and potential GDP.

A new report from the Congressional Budget Office provides some insights into one of the mechanisms linking social policy to growth, namely, labor force participation (LFP). Recent LFP trends in the United States have not been favorable to growth, but a close examination of the data suggests that better social policy, especially in the areas of income support, healthcare, and disability, could significantly improve participation. Increased LFP, in turn, would boost both actual and potential GDP, making room for additional monetary and fiscal stimulus.

Recent trends in Labor Force Participation

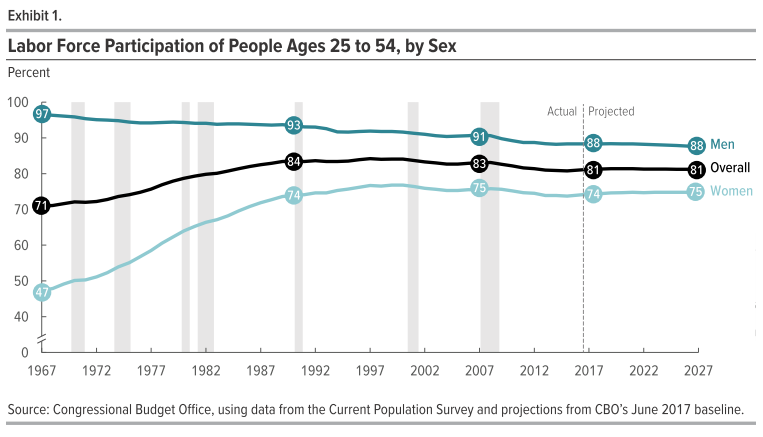

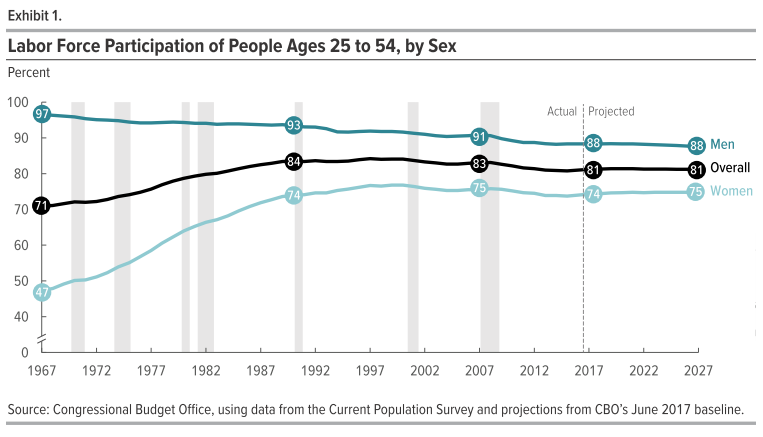

Let’s look at some of the key findings of the CBO report. First, we find that labor force participation as a whole has declined since its peak in the early 1990s. As the following chart shows, LFP rates are expected to stabilize for men and increase slightly for women over the next decade, but not to return to their former peak values. (Gray bars denote recessions.)

Second, we find that decreases in participation have not been uniform. As the next chart shows, declines in LFP have been especially sharp for less educated men and women. In contrast, the report notes that gender and ethnicity have had little effect on the overall trend. Although LFP rates are lower for minority groups and women, they have actually recovered slightly more for those groups than for white men since the trough of the recession.

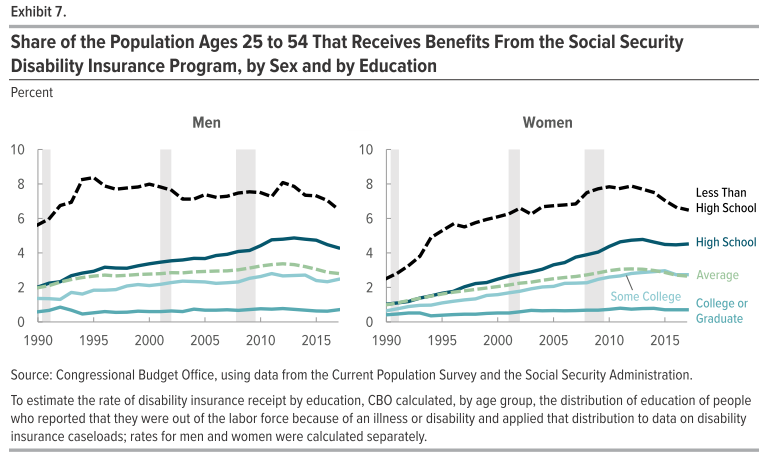

Third, the next chart from the CBO report shows that disability contributed significantly to the decline in LFP, especially for those with less education. Lower LFP due to disability is a result, in part, of an actual decrease in the average health of the working-age population, but that is not the whole story. Participation also falls because lower-income workers turn to Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) as a substitute form of long-term unemployment insurance. But once they are enrolled in SSDI, their incentives to rejoin the labor force are greatly reduced. As a result, the disability rate falls only slowly during economic recoveries—an example of hysteresis in labor markets.

Leave A Comment