That was a title of a conference last summer held at the Swiss National Bank, and noted in this post. Mark A. Wynne and Julieta Yung discuss the conference proceedings.

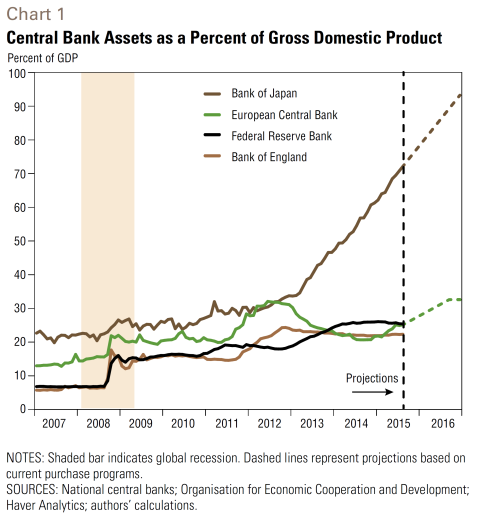

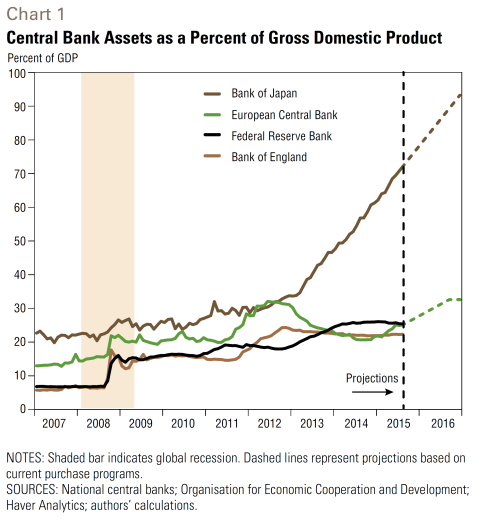

A key motivation for the conference is based on this graph.

Source: discuss.

They write:

Central banks around the world launched extraordinary monetary policy responses to the global financial crisis of 2007–09 and the European debt crises that began in 2010. Some were coordinated; all were directed at fulfilling domestic mandates for price and financial stability and supporting real economic activity.

Fears that the dramatic expansion of central bank balance sheets (Chart 1)—a concomitant of the unconventional part of the policy response—would lead to higher inflation at the consumer level have so far proven unfounded, whether due to still abundant slack in many countries or to well anchored inflation expectations.

But it has been argued that an extended period of ultra-easy monetary policy is manifesting itself in excessive risk taking, bubbles in certain asset classes and price pressures in countries that are recipients of internationally mobile capital. This capital, in search of higher yields, could ultimately lead to higher inflation globally.

The experience of recent years has challenged our understanding of the transmission of monetary policy across national borders as well as the implications of financial interconnections and the global financial cycle for inflation spillovers and monetary control. Moreover, it has prompted us to reconsider the short- and long-run trade-offs between structural reforms and monetary policy during international crises and the global implications of policy responses to the financial crisis.

Leave A Comment