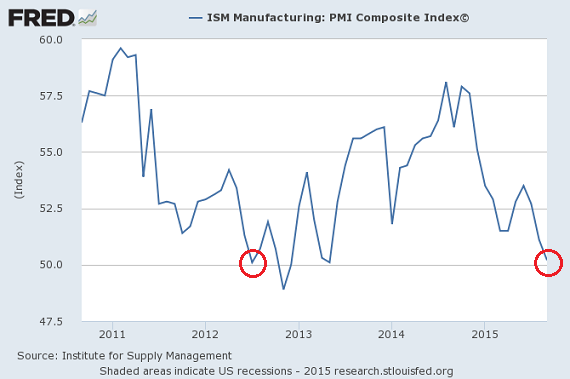

By July of 2012, a wide range of indicators suggested that the U.S. economy was flirting with trouble. Job growth was decelerating. Business investment was deteriorating. Meanwhile, manufacturing via the ISM Manufacturing Survey (PMI) was flirting with contraction.

Up until that moment in time, the Federal Reserve had already left rates at zero percent for three-and-a-half years. What’s more, they had already created trillions of electronic dollars to acquire government debts and push borrowing costs to unfathomable lows to ward off a double-dip recession (i.e., “QE1,” “QE2,” “Operation Twist”). However, the end of those programs seemed to show that the U.S.economy was still too fragile to stand on its own.

Not surprisingly, leaked rumors about a more awe-inspiring economic jolt began taking over the July 2012 business headlines. Terms like “QE3, “QE Forever,” and “QE Infinity” had been making the rounds. Indeed, by September of 2012, The Fed had unleashed an open-ended bond buying program that rivaled anything investors had seen previously.

Fast forward three years. Once more, the U.S. economy is flirting with trouble. The percentage of 25-54 year-olds (19.5%) that are out of work has risen sharply. (Retirees? College students?) Median household income is sagging. Business investment in research, plants, equipment and human resources development is virtually non-existent, with virtually all after-tax profits going to share buybacks and shareholder dividends. Non-revolving consumer credit has grown from 14.6 percent of after-tax income at the end of the recession (6/2009) to 18.7 percent (6/2015). And manufacturing via PMI? Falling throughout 2015 and hanging on by a thread (50.2), we’re right back to the type of environment that prompted previous calls for more quantitative easing (QE) “cowbell.”

From an investment standpoint, the demand for U.S. treasury bonds in recent government auctions still points to risk aversion. Recall Monday’s 3-month T-Bill auction (10/5) where $21 billion had been acquired at 0%. Zero percent! It was the calls for more quantitative easing (QE) “cowbell. On Wednesday (10/7), another $21 billion went to auction on 10-year Treasury bonds. The high yield of 2.066% was the lowest since April. Equally worthy of note (no pun intended), the indirect bidding component that includes significant central banks acquired $13.1 billion (62.2%) – the second highest percentage on the record books.

Leave A Comment