In a Brookings Institute blog post from April, former Federal Reserve Bank Chairman Ben Bernanke repeated his claim that cutting interest rates is necessary for maintaining economic growth. Bernanke claims that suppressing inflation-adjusted interest rates further into the negatives sometimes becomes necessary, Bernanke wrote:

[I]n a persistently low-rate world we could frequently see situations in which the Fed would like to cut its policy rate but will be unable to do so. The result could be subpar economic performance.”

It’s not the first time Bernanke has claimed that lowering interest rates stimulates an economy, even if those interest rates go negative. Bernanke wrote in 2016:

Overall, as a tool of monetary policy, negative interest rates appear to have both modest benefits and manageable costs; and I assess the probability that this tool will be used in the U.S. as quite low for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, it would probably be worthwhile for the Fed to conduct further analysis of this option.”

And in 2015:

A premature increase in interest rates [in the post-Great Recession economy] engineered by the Fed would therefore have likely led after a short time to an economic slowdown and, consequently, lower returns on capital investments. The slowing economy in turn would have forced the Fed to capitulate and reduce market interest rates again.”

The claim that lowering interest rates stimulates borrowing and investment, leading to economic growth, has long been a Keynesian article of faith. However, suppressed interest rates also discourage saving, and savings also leads to increased investment. So, does real-world economic data back up the Keynesian dogma that central banks artificially lowering interest rates increases economic growth?

In a word, no.

Interest Rates and Growth

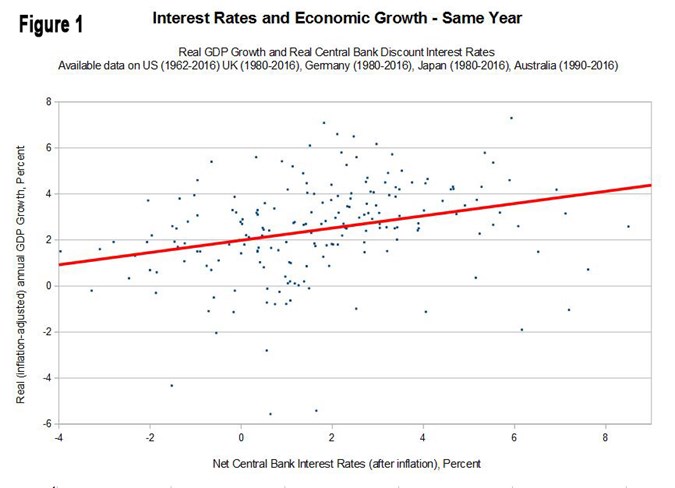

Lower interest rates tend to depress economic growth, rather than strengthen it, according to data published by modern central banks. Data provided by the US Federal Reserve Bank, the UK Bank of England, the German Bundesbank, the Bank of Japan and the Reserve Bank of Australia (one of the few central banks that still maintains positive net interest rates) demonstrate that countries with higher interest rates tend to have slightly higher economic growth. [See Figure 1]

While the correlation is only a 0.25 percent increase in GDP growth for every one percent increase in central bank interest rates, the cumulative effect of higher interest rates over several years may be substantial.

There’s also a slight positive correlation between high-interest rates and economic growth the year following the interest rate fixture. [See Figure 2] For example, if Japan sets its interest rates at 0.383 in 2005, what is the GDP growth rate in 2006? The chart means that low-interest rates may have a negative impact on economic growth in future years.

Leave A Comment