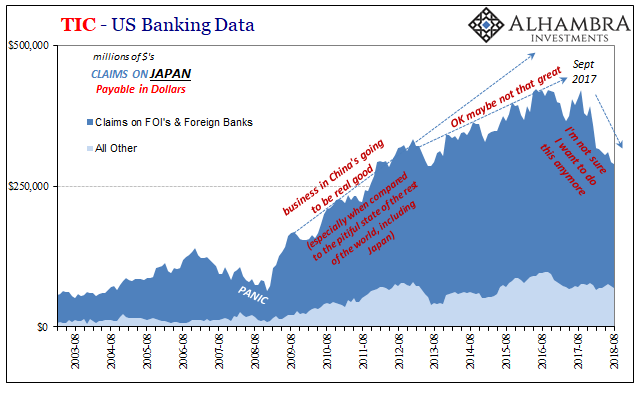

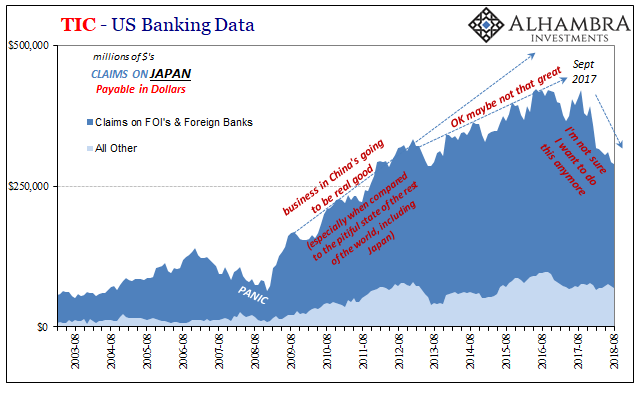

The Asians are selling their Treasuries again, which can only mean one thing. The mainstream media will offer all sorts of explanations as to why that might be and not a single one will be correct. China and Japan are offloading US$ assets primarily federal government debt for vastly different reasons. Their decisions spring from the same source, but Japan’s position in the global reserve system is nothing like China’s.

Here’s one explanation for Japan’s dumping of treasuries offered back in February that probably sounded good when it was written. Weak dollar:

Japanese investors may be America’s bond bears.

They are shifting toward selling U.S. Treasury bonds and other dollar-based debt after fears have picked up in recent weeks that the Trump administration’s budget and other policies add up to a weak dollar.

The repositioning of Japanese banks tells us a lot about this last year, for sure, but not in any way like what is described above. The dollar is no longer weak, but Japan is still selling.

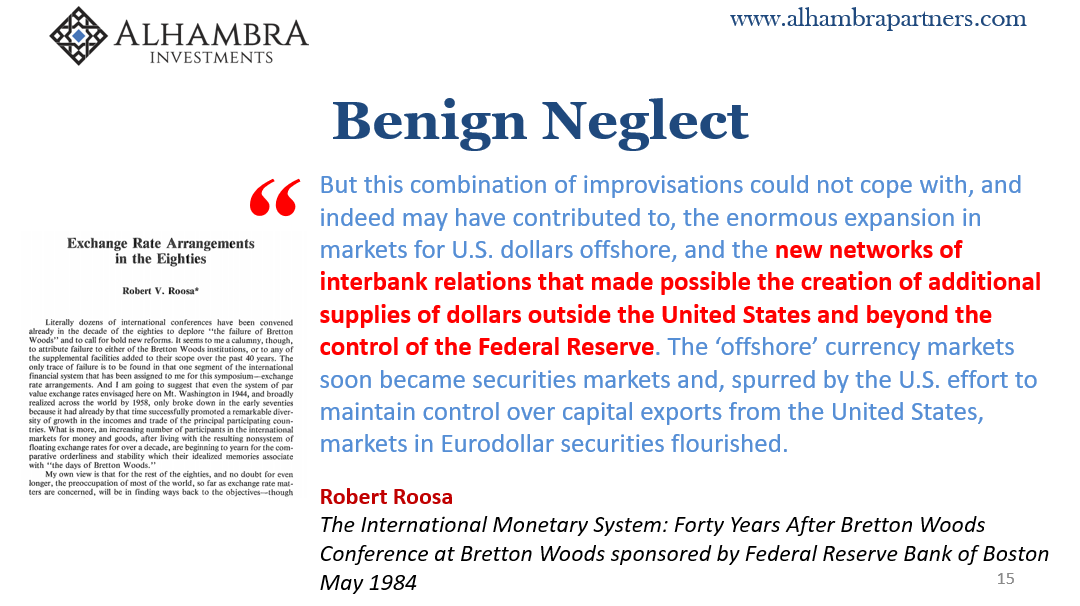

The problem stems from gross misunderstanding of the very idea of a global reserve currency, and therefore the lack of appreciation for the current one. I focused on just this aspect of intellectual darkness, what was once characterized as “benign neglect”, in my speech last week to the CFA Society of the Cayman Islands.

Their topic was globalization and my contribution to it was to try to help understand first what a global reserve currency actually is so as to further appreciate its role in how the world came to be this way. As I said last week:

We so often hear about a global reserve currency, almost always in considering which one might qualify rather than what it specifically means to qualify. What is the current global reserve currency? What is a global reserve currency?

Anyone attempting to answer the first question will inevitably be wrong. The reason is found in the little appreciation for the second. What is a global reserve currency?

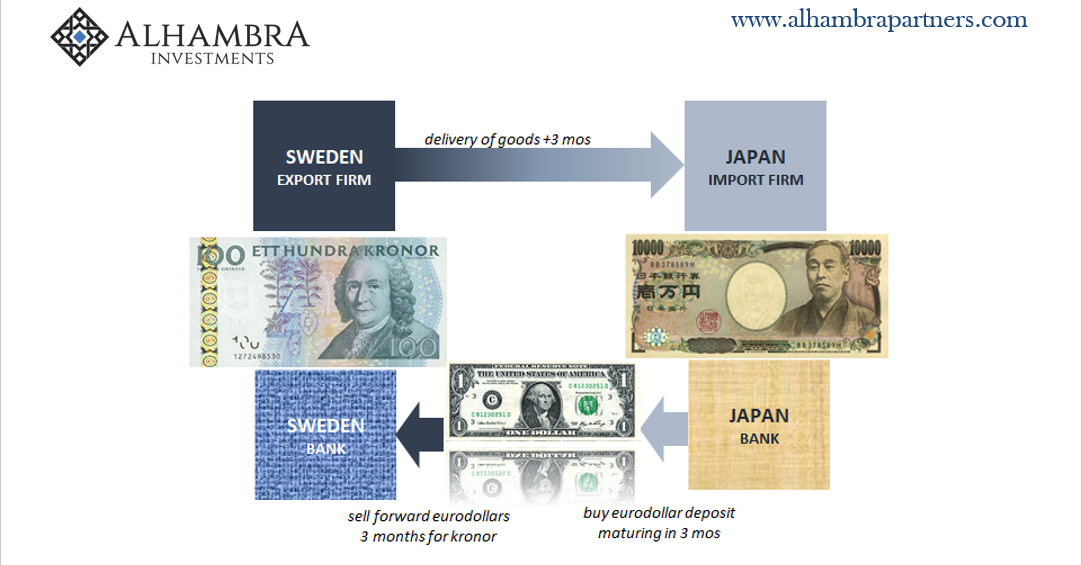

Quite simply, the world needs dollars to intermediate global trade. The more global trade, the greater demand for dollars.

Historically, as Robert Triffin once pointed out, this was a bad match. The domestic supply of dollars could never fill the role required of it under this international arrangement. Bretton Woods had in its design an inherent flaw.

Conventional wisdom says that the international system finally broke free when President Nixon closed the gold window in August of 1971, thereby severing the link between dollars and gold. The end of Bretton Woods had meant no country could claim gold reserves from America for the surplus of dollars offered to them.

Nope. That’s not what really happened.

There was, in those early days, a multiplier effect. Once any bank around the world had obtained dollar liabilities for any reason, they could then multiply those offshore such that the global supply of eurodollars would increase immensely while at the same time the domestic money supply did not change.

Recalling Triffin’s Paradox, the eurodollar had solved it long before anyone in official capacity realized that fact.

The world needs dollars for globalization and trade, and the eurodollar system of closely connected banks (balance sheet capacity) supplies them.

Leave A Comment