From the standpoint of our analysis, it is clear that there are far greater similarities than possible differences between monetarists and Keynesians. Indeed Milton Friedman himself has acknowledged: “We all use the Keynesian language and apparatus. None of us any longer accept the initial Keynesian conclusions.” Peter F. Drucker, for his part, indicates that Milton Friedman is essentially and epistemologically a Keynesian:

His economics is pure macroeconomics, with the national government as the one unit, the one dynamic force, controlling the economy through the money supply. Friedman’s economics are completely demand-focused. Money and credit are the pervasive, and indeed the only, economic reality. That Friedman sees money supply as original and interest rates as derivative, is not much more than minor gloss on the Keynesian scriptures.

Furthermore, even before the appearance of Keynes’s The General Theory, the principal monetarist theorists of the Chicago school were already prescribing the typical Keynesian remedies for depression and fighting for large budget deficits.

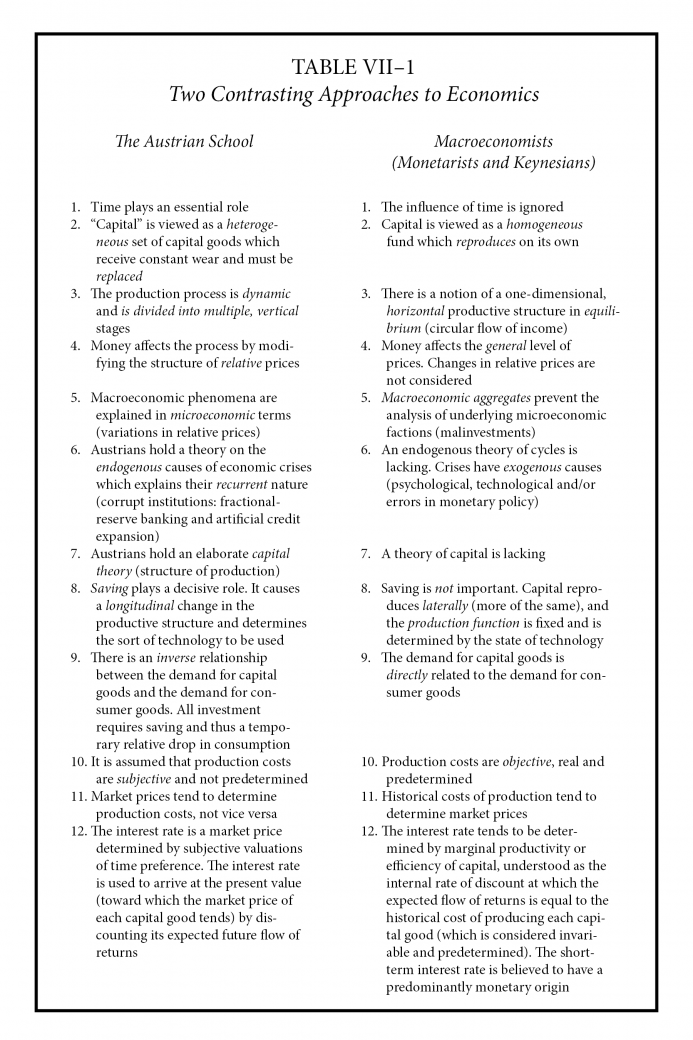

Table VII-1 [see chart in PDF format] recapitulates the differences between the Austrian perspective and the major macroeconomic schools. The table contains twelve comparisons that reveal the radical differences between the two approaches.

Table VII-1 groups monetarists and Keynesians together because their similarities far outweigh their differences. Nevertheless, we must acknowledge that certain important differences do separate these schools. Indeed, though both lack a capital theory and apply the same “macro” methodology to the economy, monetarists concentrate on the long-term and see a direct, immediate and effective connection between money and real events. In contrast Keynesians base their analysis on the short-term and are very skeptical about a possible connection between money and real events, a link capable of somehow guaranteeing equilibrium will be reached and sustained. In comparison, the Austrian analysis presented here and the elaborate capital theory on which it rests suggest a healthy middle ground between monetarist and Keynesian extremes. In fact for Austrians, monetary assaults (credit expansion) account for the system’s endogenous tendency to move away from “equilibrium” toward an unsustainable path. In other words, they explain why the capital supply structure tends to be incompatible with economic agents’ demand for consumer goods and services (and thus Say’s law temporarily fails to hold true). Nonetheless certain inexorable, microeconomic forces, driven by entrepreneurship, the desire for profit, and variations in relative prices, tend to reverse the unbalancing effects of expansionary processes and return coordination to the economy. Therefore Austrians see a certain connection — a loose joint, to use Hayek’s terminology — between monetary phenomena and real phenomena, a link which is neither absolute, as monetarists claim, nor totally non-existent, as Keynesians assert.

Leave A Comment