from the Cleveland Fed

— this post authored by Ben R. Craig and Sara Millington

Before the financial crisis, the federal funds market was a market in which domestic commercial banks with excess reserves would lend funds overnight to other commercial banks with temporary shortfalls in liquidity. What has happened to this market since the financial crisis? Though the banking system has been awash in reserves and the federal funds rate has been near zero, the market has continued to operate, but it has changed.

Different institutions now participate. Government-sponsored enterprises such as the Federal Home Loan Banks loan funds, and foreign commercial banks borrow.

Although monetary policy has focused on setting an appropriate level for the federal funds rate since well before the financial crisis, the mechanics since the crisis have changed. In response to the crisis, several new policies were enacted that altered the structure of the federal funds market in profound ways. On the borrowing side, the Fed’s large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) flooded the banking system with liquidity and made it less necessary to borrow. In addition, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) introduced new capital requirements that increased the cost of wholesale funding for domestic financial institutions. On the lending side, the Federal Reserve now pays some financial institutions interest on their excess reserves (IOER). When institutions have access to this low-risk alternative, they have less incentive to lend in the federal funds market.

In this environment, the institutions willing to lend in the federal funds market are institutions whose reserve accounts at the Fed are not interest-bearing. These include government-sponsored entities (GSEs) such as the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs). The institutions willing to borrow are institutions that do not face the FDIC’s new capital requirements and do have interest-bearing accounts with the Fed. These include many foreign banks. As such, the federal funds market has evolved into a market in which the FHLBs lend to foreign banks, which then arbitrage the difference between the federal funds rate and the rate on IOER.

This Commentary describes the evolution of the federal funds market since the crisis. While research is ongoing about the effect these shifts in the market will have on the Fed’s ability to conduct monetary policy, events of the past decade highlight the large effect that small interventions like FDIC capital requirements can have on the structure of the financial system.

The Federal Funds Market before the Crisis

Before the financial crisis, the federal funds market was an interbank market in which the largest players on both the demand and supply sides were domestic commercial banks, and in which rates were set bilaterally between the lending and borrowing banks. The main drivers of activity in this market were daily idiosyncratic liquidity shocks, along with the need to fulfill reserve requirements. Rates were set based on the quantity of funds available in the market and the perceived risk of the borrower.

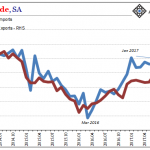

Although the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) sets a target for the federal funds rate, the actual funds rate is determined in the market, with the “effective” rate being the weighted average of all the overnight lending transactions in the federal funds market. When the effective rate moved too far from the Fed’s target before the financial crisis, the FOMC adjusted it through open market operations. For example, if the Fed wanted to raise the effective rate, it would sell securities to banks in the open market. Buying those securities reduced the funds banks had available for lending in the federal funds market and drove the interest rate up. The Fed’s portfolio of securities consisted mainly of treasury bills, generally of short maturity, and its balance sheet was small.

Leave A Comment