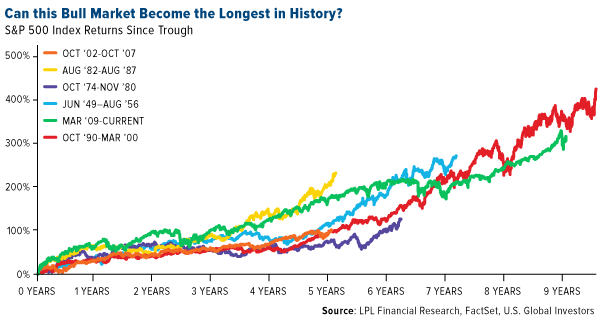

Friday marked the ninth anniversary of the stock bull market, the second longest since World War II following the spectacular run in the 1990s that finally met its match when the tech bubble burst in March 2000. The current expansion, which some consider the “most hated bull market in history,” has largely been fueled by extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy in the form of massive money printing and near-zero interest rates. It’s withstood a number of significant headwinds, including a relatively slow economic recovery, the collapse in the price of oil and other commodities, ongoing conflict in the Middle East and an especially nasty presidential campaign cycle. If it can avoid dropping more than 20 percent in the next six months, it will become the longest-lasting ever.

No doubt you’ve heard before that bull markets don’t die of old age. I can’t say for sure what will end this particular business cycle—no one can—but we’re seeing huge shifts in monetary and fiscal policy right now that investors can’t afford to ignore. As I often say, government policy is a precursor to change.

Unintended Consequences of Steel Tariffs

For one, the decade-long era of easy money is coming to an end. The Federal Reserve is unwinding its enormous balance sheet, its enormous balance sheet, which carries some risk.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration is ratcheting up its protectionist trade policies. After surprising markets in recent days with plans to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, President Trump signed the authorization Thursday afternoon, applying taxes broadly to all countries except Canada and Mexico. It was greatly feared that Canada, the number one supplier of steel and aluminum to the U.S., would be included, but it appears someone managed to change the president’s mind. When former President George W. Bush imposed a steep 30 percent tariff on steel imports in 2002, Canada was likewise spared.

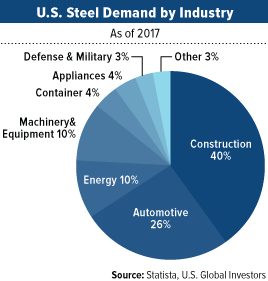

The 2002 tariff, by the way, had some serious unintended consequences that critics of Trump’s policy hope are not repeated. A report put out by the Consuming Industries Trade Action Coalition (CITAC) found that about 200,000 Americans, in every U.S. state, lost their jobs in 2002 as a result of higher steel prices, representing some $4 billion in lost wages. More people, in fact, lost their jobs than the total number of people working in the domestic steel industry itself. Not surprisingly, a quarter of lost jobs occurred in steel-consuming industries such as machinery and equipment, automotive and parts manufacturers.

Leave A Comment