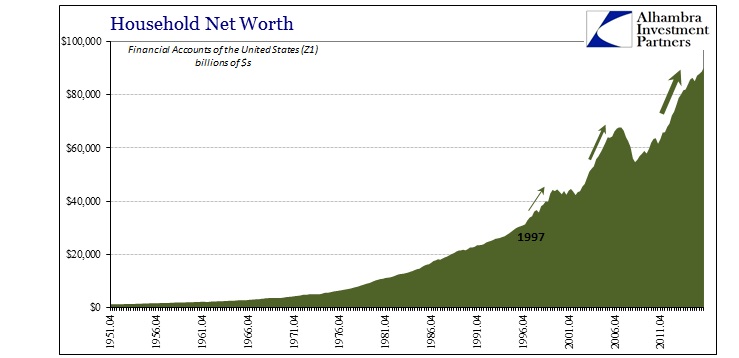

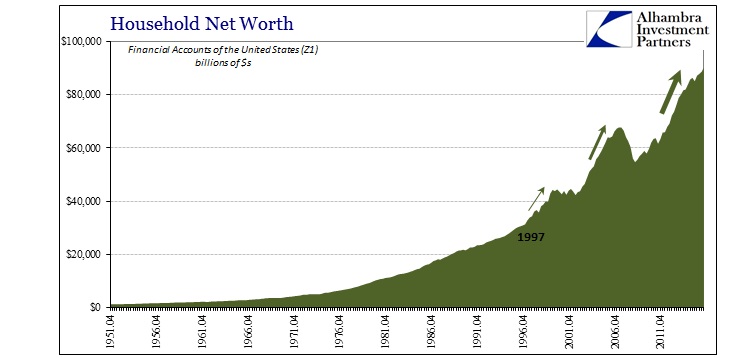

Household net worth in the United States surpassed $90 trillion for the first time in Q3 2016, according to the latest estimates from the Federal Reserve’s Financial Accounts of the United States (Z1). That’s up sharply from $67.9 trillion now estimated (with revisions) for Q3 2012 when QE3 was introduced. Despite a massive gain of just about a third, Nominal Final Sales to Domestic Purchasers (from the BEA’s GDP data) have increased but 14.5%, a pathetic (nominal) 3.4% compounded annual rate.

We should not expect a dollar for dollar increase in spending for paper “wealth”, of course, but if this QE “wealth effect” was as efficient in the past almost five years as it was, theoretically, during the worst of the dot-com bubble, Nominal Final Sales to Domestic Purchasers would be $2 trillion more in the latest quarter. That would have been a 26% gain in final sales since QE3, or 6.1% compounded, nearly twice the rate above what actually occurred.

It should be painfully clear even to economists that there is no wealth effect, especially where paper “wealth” is involved as a matter of arguable imbalance (i.e., asset bubbles). There is no detectable relationship between net worth and spending, even though by common sense there might be. To the left, that is a function of “inequality”; to the right, a matter of income distribution; to Economists, it’s the Baby Boomers.

Whatever the interpretation, this should remove asset prices from all economic considerations, particularly those of monetary policy. My own view is that it was never a strong appeal in terms of inside policy discussions, more so included in outward proclamations and literature solely because it was practically the only way to assign any success at all to the QE’s. The US and global economy failed to ignite in embarrassing fashion, especially after 2014, so at least economists had stock and housing prices (the main components of household net worth) with which to suggest a minimum of QE achievement.

Leave A Comment