Cries for Going Totally Crazy are Intensifying

What are the basic requirements for becoming the chief economist of the IMF? Judging from what we have seen so far, the person concerned has to be a died-in-the-wool statist and fully agree with the (neo-) Keynesian faith, i.e., he or she has to support more of the same hoary inflationism that has never worked in recorded history anywhere. In other words, to qualify for that fat 100% tax-free salary (ironically paid for by assorted tax serfs), one has to be in favor of central economic planning and support policies fully in line with today’s economically illiterate orthodoxy. Meet Maurice Obstfeld, who has just taken the mantle.

New IMF chief economist Maurice Obstfeld (left) and fellow monetary crank Haruhiko “Peter Pan” Kuroda, governor of the BoJ

Photo credit: Yoshikazu Tsuno / AFP

For all we know the man is merely misguided and otherwise a nice person (in fact, he’s laughing a lot in photographs and seems a personable enough fellow). But his proposals could eventually affect the lives of countless people in the whole world, so he is fair game for robust criticism. We personally believe that he and other members of our “enlightened” technocratic ruling class should resign without delay and start looking for productive work instead of parasitizing and hampering the ever shrinking class of genuine wealth producers, but it seems unlikely that they will be interested in our opinion.

There once was a time when monetary cranks of the sort in charge nearly everywhere today were laughed out of the room. Today they are perfectly free to drive what is left of the market economy over the cliff. Mr. Obstfeld turns out to be yet another in a long list of luminaries belly-aching about (non-existing) “deflation” – this is to say, the alleged danger that the purchasing power of consumer incomes and savings might increase at some point. Allegedly, this remote eventuality has to be guarded against at all costs.

According to the WSJ:

“The Bank of Japan and other central banks around the world may need to try radical new easy-money policies to stave off the rising specter of deflation and revive sickly economic prospects, the International Monetary Fund’s new chief economist warns.

“I worry about deflation globally,” new IMF Economic Counselor Maurice Obstfeld said in an interview ahead of an annual IMF research conference that focuses this year on unconventional monetary policies and exchange rate regimes. “It may be time to start thinking outside the box.”

Weak—and in some cases falling—price growth has plagued Japan, Europe, the U.S. and other major economies since the financial crisis. Plummeting commodity prices are exacerbating the so-called “lowflation” and deflation problems that curb investment, spending and growth.

Surveying several dozen of the largest economies around the world, Mr. Obstfeld said the number of countries experiencing low inflation is rising. Combined with slowing emerging market output, ballooning government debt and monetary policy constrained by the lower limits of interest rates, the deflation risk is fueling fears the global economy could be fast stuck into a deep low-growth mire.

We don’t deny that global economic prospects look dim at the moment. However, this is the direct result of the policies Mr. Obstfeld supports and recommends. It has absolutely nothing to do with the fact that government-doctored CPI data are for once indicating a minor slowdown in the pace of inflationary robbery by the State (from the point of view of consumers, price inflation is in essence a hidden tax).

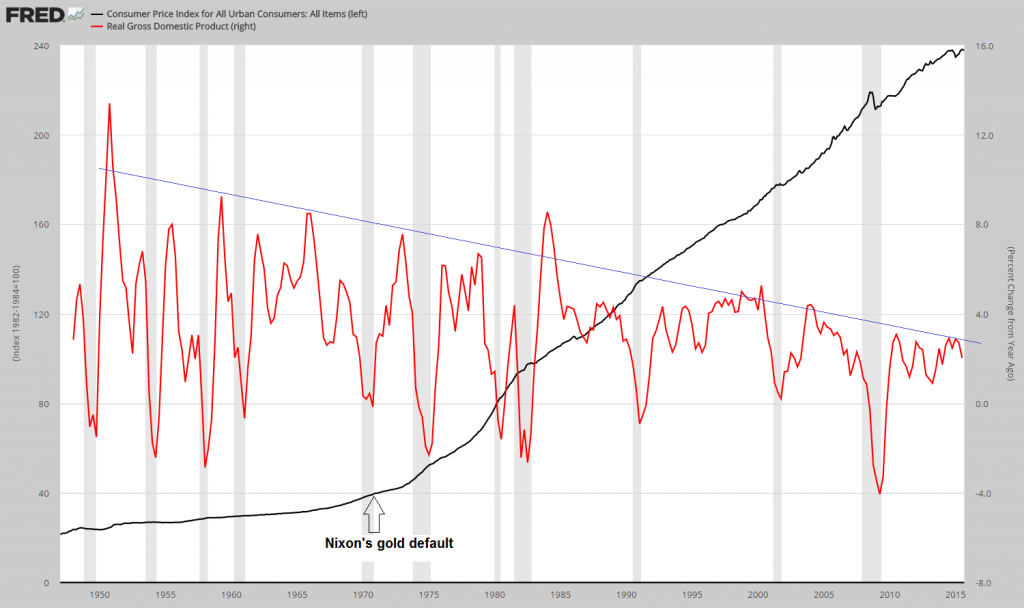

To illustrate how utterly inconsequential the recent slight decline in the rate of change of CPI is in a larger context, consider simply the long term trend in US CPI. We have contrasted it with quarterly annualized GDP growth rates, because they show something important: the steeper the trend in money and credit supply expansion and consequent “price inflation” has become over time, the more real GDP growth has actually slowed (about the only thing GDP data are remotely useful for are historical comparisons and even those have to be taken with a grain of salt: today’s GDP data are actually overstating growth relative to the data employed in past decades). One would expect positivist mainstream economists to take note of such empirical facts and perhaps even wonder if there could be a connection – we have yet to see that happen though.

CPI “inflation” vs. real GDP growth – the blue trend line is mainly meant to serve as a visual aid

An even starker illustration is provided by economic growth in the decades prior to the establishment of the Federal Reserve. We have written about this previously in Presidential Musings About Inequality. Here is the relevant passage:

“[…] the period of the greatest real economic growth in the US, a period that was marked by sharp growth in the real incomes of the broadest possible swathe of the population, was that otherwise dreaded age of the ‘robber barons’, the Gilded Age, in the decades prior to the founding of the Federal Reserve. Prices during that era of extremely small money supply growth were almost continually in a mildly declining trend, thereby inexorably raising the real incomes of workers and the then up and coming middle class. It is interesting in this context to look at the Wikipedia entry on the Gilded Age, which is full of complaints about the poverty of the time and the two crisis that ‘interrupted growth’. At first one gets the impression that it must have been a truly terrible time (even the term ‘Gilded Age’ was actually meant to be sarcastic). However, a few paragraphs in, one finds the following:

“During the 1870s and 1880s, the U.S. economy rose at the fastest rate in its history, with real wages, wealth, GDP, and capital formation all increasing rapidly. For example, between 1865 and 1898, the output of wheat increased by 256%, corn by 222%, coal by 800% and miles of railway track by 567%. Thick national networks for transportation and communication were created. The corporation became the dominant form of business organization, and a scientific management revolution transformed business operations. By the beginning of the 20th century, per capita income and industrial production in the United States led the world, with per capita incomes double that of Germany or France, and 50% higher than Britain. The businessmen of the Second Industrial Revolution created industrial towns and cities in the Northeast with new factories, and hired an ethnically diverse industrial working class, many of them new immigrants from Europe.

Wealthy industrialists and financiers such as John D. Rockefeller, Andrew W. Mellon, Andrew Carnegie, Henry Flagler, Henry H. Rogers, J. P. Morgan, Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, Cornelius Vanderbilt of the Vanderbilt family, and the prominent Astor family would sometimes be labeled “robber barons” by their enemies. Many of these captains of industry, in addition to building up the American economy, participated in immense acts of philanthropy. Andrew Carnegie, who gave away over 90% of his wealth, said philanthropy was their duty–it was the “Gospel of Wealth”. Private money endowed thousands of colleges, hospitals, museums, academies, schools, opera houses, public libraries, and charities. John D. Rockefeller, for example, donated over $500 million to various charities, slightly over half his entire net worth.

This emerging industrial economy quickly expanded to meet the new market demands. From 1869 to 1879, the US economy grew at a rate of 6.8% for NNP (GDP minus capital depreciation) and 4.5% for NNP per capita.

The economy repeated this period of growth in the 1880s, in which the wealth of the nation grew at an annual rate of 3.8%, while the GDP was also doubled. Real wages also increased greatly during the 1880s. Economist Milton Friedman states that for the 1880s, “The highest decadal rate [of growth of real reproducible, tangible wealth per head from 1805 to 1950] for periods of about ten years was apparently reached in the eighties with approximately 3.8 percent.”

Not so terrible a time after all! […] 1. ‘deflation’ (declining prices) is not inimical to economic growth, as the Federal Reserve and its apologists maintain (the opposite appears to be the case), and 2. the less central economic planning there is and the sounder the money employed, the more economic growth and economic advancement of the poor and middle class strata of society can be expected.

Leave A Comment