In this analysis we will take a look at something deeply personal – which is how the $20 trillion United States national debt may change the day-to-day quality of life for savers and retirees in the decades ahead. That is likely a somewhat unusual perspective for many savers and investors.

On the one hand, we have what are often thought of as abstract economic concepts – such as how large will the national debt be in 10 or 20 years? How will Federal Reserve actions to increase interest rates change future government deficits and debts?

On the other hand, we have something that is typically presented as being entirely different, which is individual financial planning. What are the savings and investment choices that we need to make today that will help determine what our standard of living may be in retirement 10, 20 or 30 years from now?

The two are often treated as occurring in what could be called two separate universes, with no connection between the nation as a whole and our individual financial situations and choices.

What we will establish in this analysis is that there is a direct and tangible connection between what is happening with the national debt and what our personal future financial situation may be. Indeed, the well-understood measures that a heavily indebted government uses to maintain financial solvency may play a critical role in determining both actual investment outcomes and our future standard of living.

The Impact Of Rising Interest Rates On A Heavily Indebted Nation

This is the third analysis in a series, and while it is not necessary to have read the first two analyses, it could be helpful if some of the concepts explored are not intuitive for you.

In the first analysis linked here, we established the powerful connection between future interest rates and the financial solvency of the federal government.

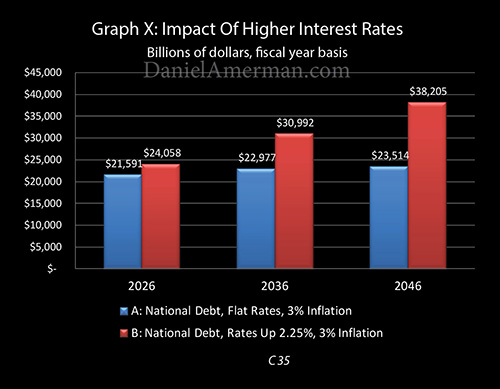

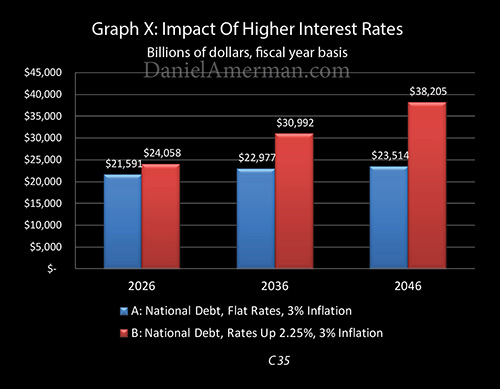

More specifically, we examined the effects on U.S. government deficits and the national debt if the Federal Reserve were to carry through with raising interest rates by a total of 2.25% from the post-crisis low.

The conclusions were that over the short term of the next 1-3 years, the Federal Reserve does have a great deal of latitude when it comes to raising interest rates. This is because the federal debt has short-term, medium-term and long-term components, and most of the national debt is not initially impacted.

Within 5-11 years, however, maintaining higher interest rates comes at a very high cost as ever more of the national debt rolls over and is reissued at the new interest rates. This would have the effect of doubling the interest payments on the national debt, while drastically increasing the size of the annual deficits.

Graph X above shows the future national debt in inflation-adjusted dollars. The blue bars show future debts with no increase in interest rates, and the red bars show the impact of higher interest rates. As explored in the first analysis, when we go to the longer term of 15-20 years and beyond, the Fed’s stated plans would create a financial catastrophe scenario, because of the higher exponential compounding rate of 4.5% interest payments versus 2.25% interest payments.

The Inflation Loophole

While the first analysis established the problems with heavily indebted nations increasing interest rates, the second analysis linked here found the loophole: moderately increase the rate of inflation, and any negative effects from moderately increasing interest rates can be overcome.

As developed in that analysis, our base Scenario A is the blue bar, and it shows that with no increases in interest rates from the floor, and with historically average inflation, the inflation-adjusted value of the national debt at the end of fiscal year 2026 would be about $21.6 trillion.

If the Fed’s total 2.25% increase in interest rates goes through in full and is maintained, then this enough to create the red bar of Scenario B, and an increase in the national debt to about $24 trillion. That is a big problem, and it gets much worse with time.

Unless…inflation is also increased. If that happens, we get the yellow bar of Scenario C, where the harmful impact of what would otherwise happen with an increase in interest rates is completely neutralized, and the inflation-adjusted value of the debt is a “mere” $19.8 trillion.

This could be called a “miracle” solution of sorts. Because the United States is so heavily indebted, the increase in interest rates that savers so badly need would ordinarily have the effect of sending government deficits and debts spiraling upwards, and going potentially out of control. But there is a way out – and this is something that government economists understand very well indeed – and that is to use a higher rate of inflation to negate the damage that would otherwise be caused by higher interest rates.

(In order to tightly focus on the critical but little understood relationship between 1) retirement savings, 2) the national debt, 3) interest rates and 4) inflation, a number of simplifying assumptions were made. The most important is that “net benefits” – the sum of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid – were left constant as a percentage of the economy at fiscal year 2016 levels. This spending is expected to rise dramatically, which produces much larger deficits over time than those shown.)

The Personal Price Of The “Miracle” Solution

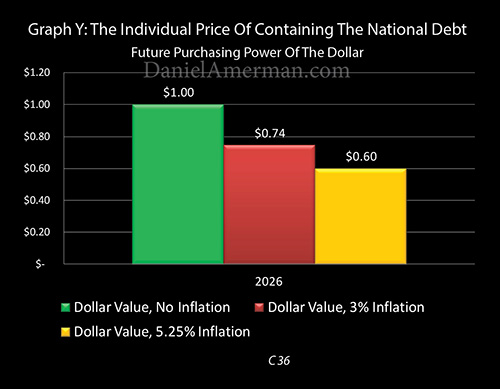

There is however a price that is paid by us all. Graph Y above shows the value of the dollar over time.

If there were no inflation – then we would have the green bar, and the purchasing power of each of our dollars would remain at $1.00.

We have, however, had inflation as a matter of deliberate governmental policy since the United States went off the domestic gold standard in 1933. If we experience roughly historically average inflation of 3% per year, then the dollar becomes worth 74 cents by the end of fiscal year 2026 (the actual average rate of inflation between 1933 and 2017 is 3.54%, we are rounding down to keep this analysis conservative).

The red bar in Graph Y shows the impact of normal historical inflation reducing the value of the dollar to 74 cents. However, that same rate of inflation creates the problem of the red bar of the national debt surging upwards in Graph X.

The nation knocks the red national debt bar down to the more manageable yellow national debt bar in Graph X, by moderately increasing the rate of inflation.

This increase in inflation also simultaneously and necessarily knocks the value of the red bar down to that of the yellow bar in Graph Y. A 5.25% national rate of inflation means that each of our personal dollars has a purchasing power of only 60 cents by 2026.

What is shown above, as the red bar is knocked down to the yellow bar in each graph, is quite direct. The linkage between how a heavily indebted nation deals with moderately higher interest rates – and what each of our dollars will actually buy for us in the future in our personal lives – is absolute.

The Greater Challenge

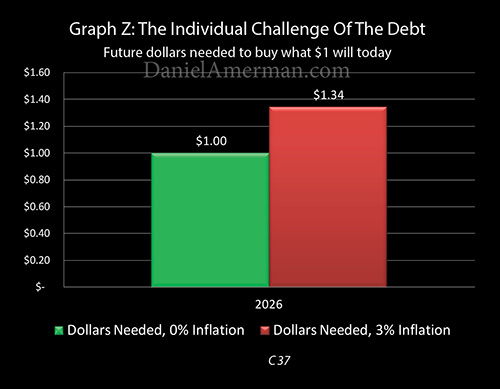

Future purchasing power is a still a little bit abstract for many people, so Graph Z above is intended to make what is happening more tangible and personal.

The green bar is the same as in Graph Y – if there were no inflation, then all we would need is a dollar in the future to buy what a dollar will today.

Leave A Comment