The world economy can appear to be operating quite well but can be hiding a major problem that causes it to be fragile. My presentation The World’s Fragile Economic Condition (PDF) explains why we should expect financial problems if energy consumption stops growing sufficiently rapidly. In fact, a global sell off in the equity markets, such as we have started to see recently, is one of the kinds of energy-related impacts we would expect.

This is Part 2 of a two-part write up of the presentation. In Part 1 (The World’s Fragile Economic Condition – Part 1), I explained that a large portion of the story that we usually hear about how the world economy operates and the role energy plays is not really correct. I explained that the world economy is a self-organized system that depends upon energy growth to support its own growth. In fact, there seems to be a “dose-response.” The faster energy consumption grows, the faster the world economy seems to grow. The period with fastest growth occurred between 1940 and 1980. During this period, interest rates were rising and workers saw their wages increase as fast as, or faster than, inflation. After 1980, the rate of growth in energy consumption fell, and the world needed to tackle its growth problems with a different approach, namely growing debt.

In this post, I explain how debt (and its partner, the sale of shares of stock) help pull the economy forward. With these types of financing, investment in new production becomes almost effortless as long as the return on investment stays high enough to repay debt with interest and to repay shareholders adequately. At some point, however, diminishing returns sets in because the most productive investments are made first.

The way diminishing returns plays out in energy extraction is by raising the cost of producing energy products. In order for the sales prices of energy products to rise to match the rising cost of production, rising demand is needed to give an upward “tug” on sales prices. This rising demand is normally produced by adding increasing amounts of debt at ever-lower interest rates. At some point, the debt bubble created in this manner becomes overstretched. We seem to be reaching that point now, especially in vulnerable parts of the world economy.

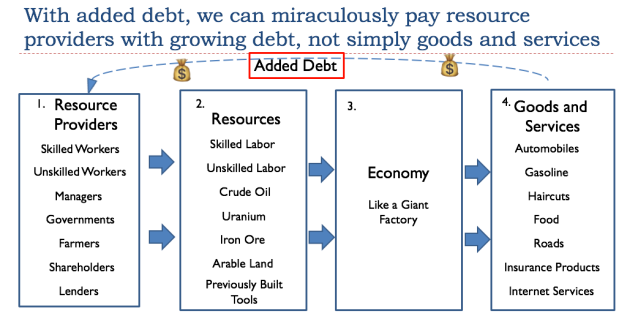

Let’s first look at a slide from Part 1, explaining the way in which the economy works like a giant factory.

As long as energy products are very inexpensive, it is possible for the economy to expand very rapidly. When this happens, the Goods and Services produced in Box 4 are able to grow so rapidly that all of the Resource Providers in Box 1 can be well compensated, simply by using a quasi-barter arrangement, facilitated by the use of money. With this approach, Resource Providers can get adequately paid using the Goods and Services produced in close to the same time period. Something of this nature occurred prior to 1970, when inflation-adjusted oil prices were less than $20 per barrel (Part 1, Slide 26).

If the growth of the economy slows, so that not enough Goods and Services are being created by the economy to use this approach, it is possible to work around the problem by adding debt. Adding debt makes it possible to substitute promised future Goods and Services for not-yet-produced Goods and Services.

Added debt makes it seem like more goods and services are available to pay resource providers.

Selling shares of stock acts very much like debt, because the funds provided by these shares also provide access to goods and services that others have already produced. In the case of the sale of shares of stock, the promises are for future dividends, capital appreciation, and partial ownership of the company.

Growing debt looks like it can solve all problems. No wonder that Keynesian economists found it so useful. But the return must remain high enough to repay debt with interest.

Borrowing money generally comes with the requirement that the amount borrowed be repaid with interest. If the energy purchased using debt allows the economy to grow fast enough, there is no difficulty in repaying debt with interest. If energy is very inexpensive (equivalent to oil cost less than $20 per barrel in inflation-adjusted price), this payback system generally works, because a large amount of energy can be purchased for a small quantity of debt.

Leave A Comment