Private payrolls in November increased by a solid 197,000 (seasonally adjusted) last month, according to this morning’s release from the US Labor Department. Although that’s well below the previous month’s upwardly revised gain of 304,000, today’s update is probably strong enough to give the green light to the Federal Reserve to start raising interest rates later this month.

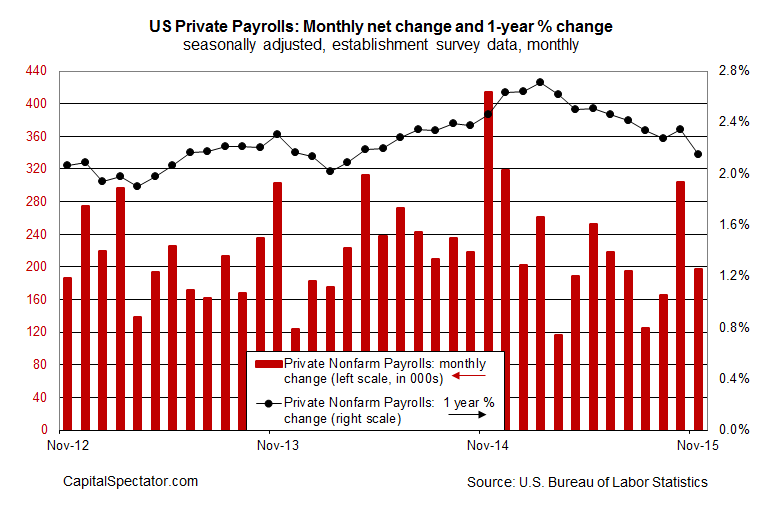

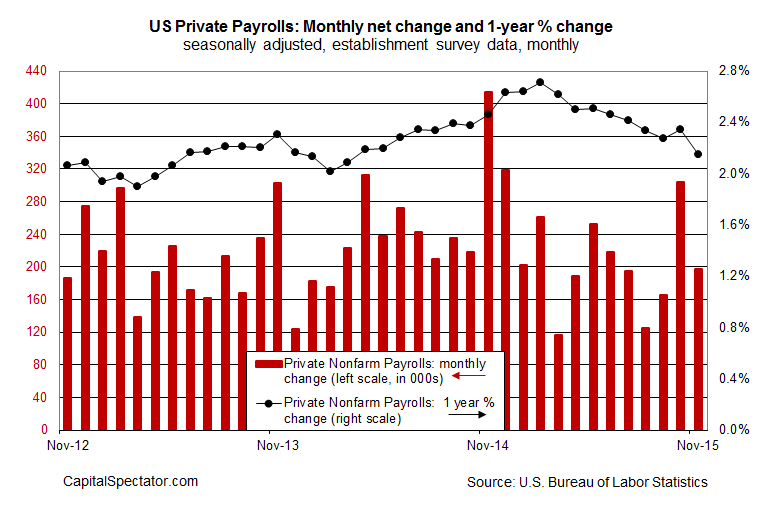

This much is certain: the November rise in nonfarm private payrolls offers fresh support for arguing that the macro trend for the US remains convincingly positive. At the same time, a potential headwind for 2016 is blowing a bit harder in today’s data: deceleration in the year-over-year change. As you can see in the chart below, the annual pace (black dots) stumbled last month, dipping to a 2.15% rise in November vs the year-earlier level. That’s still a solid advance, but the ongoing slide in the annual rate is becoming worrisome… if it continues.

Indeed, the 2.15% yearly gain in private payrolls through November is the slowest pace since March 2014 and it marks a falling trend that’s prevailed for much of the past year. This is hardly a problem in the here and now and it may not be an issue any time soon. But it’s a trend to keep an eye on for the simple reason that there’s a potential conflict brewing, namely: the arrival of monetary tightening at a time when the growth rate for payrolls has peaked and looks set to inch lower still.

We’ve seen this movie before, of course, and we’re reasonably sure how the end game plays out. The plot runs like this: the Fed starts squeezing policy when the macro trend is weakening, which eventually leads to recession.

Yes, it could be different this time. One reason for thinking so is the unusual “recovery” that’s prevailed since the Great Recession ended in mid-2009. With the Fed’s policy rate stuck at close to zero for several years, the central bank is chomping at the bit to start raising rates, if only slightly. There’s arguably enough upside bias in the economic data to support a rate hike… maybe. But even if that’s the case, it doesn’t change the fact that the current recovery is now the fifth-longest on record, which dates to the mid-1800s via NBER’s database.

Leave A Comment