Whenever the government intervenes in the economy in order to bring about what it deems to be a more beneficial outcome than would have occurred in the absence of intervention, there will be winners and losers but the overall economy will invariably end up being worse off. Moreover, it is not uncommon for one of the long-term results of the intervention to be the diametric opposite of the intended result.

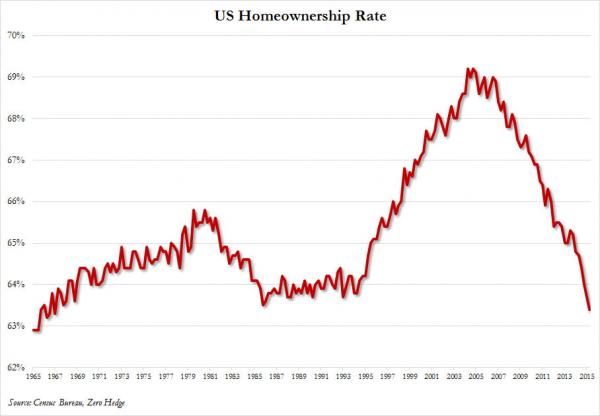

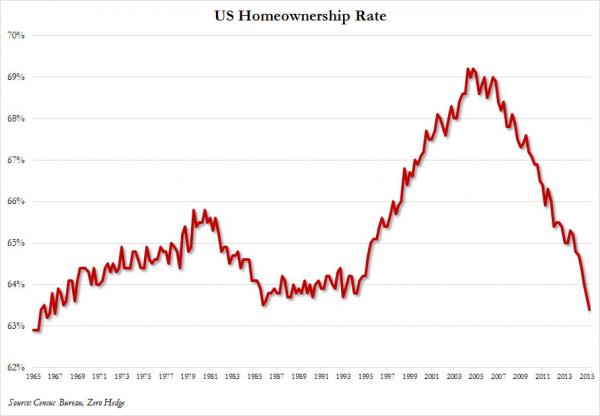

A great example of the actual result of government intervention being the opposite of the intended result is contained in a chart that formed part of a recent article at ZeroHedge.com. The chart, which is displayed below, shows the home ownership rate in the US.

Here, in brief, is the story behind the above chart.

During the Clinton (1993-2000) and Bush (2001-2008) administrations the US Federal Government decided that it would be beneficial if a larger number and a broader range of people were home-owners. The government therefore began making a concerted effort to not only increase the US home-ownership rate, but also to make home loans easier to obtain for less-qualified buyers.

This was achieved in part by the more aggressive implementation, beginning in 1993, of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977. Under the cover of the CRA, banks were forced to reduce their lending standards for lower-income groups in general and ‘minorities’ in particular. For example, government regulations created during the 1990s set bank loan-approval criteria and quotas with the aim of increasing loan quantities, and even went so far as to require the use of “innovative or flexible” lending practices to address the credit needs of low-and-moderate-income (LMI) borrowers. Of course, banks that are forced by the government to lower their standards when assessing the loan applications of less-qualified borrowers must also lower their standards for other borrowers, because they can’t reasonably approve an application from one customer and then reject an application from a better-qualified customer.

Leave A Comment