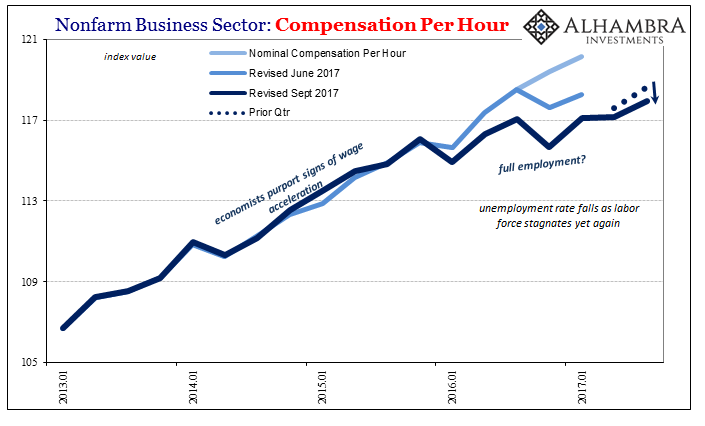

Though the BEA revised GDP slightly higher for Q3 2017, the government agency took hourly compensation out to the woodshed. On a quarterly basis, this metric of labor market wage pressures is often quite volatile. In Q4 last year, for instance, nominal hourly compensation was -4.5% Q/Q (annual rate), followed immediately by a 4.9% gain in Q1 2017.

For Q3 2017, the BEA had originally figured a 5.1% rise Q/Q for the same series. It has now been revised to just 2.7%, a much more serious downward revision than it might otherwise appear. Given the noisiness of the series, and what that likely represents in the real world, these positive quarters are more than necessary to balance out the bad ones in order to equal, over time, sustained growth. Instead, what the revised data shows is that the good periods have become both less frequent and less good.

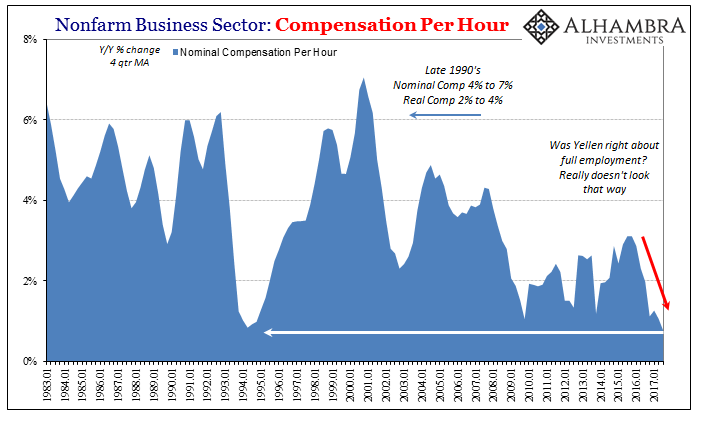

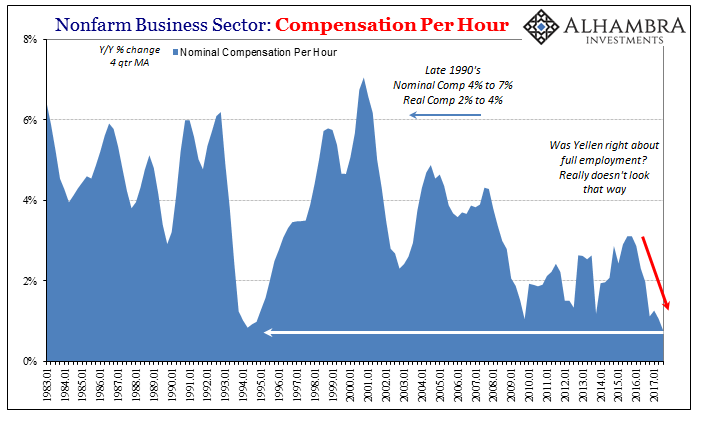

With the latest revisions, nominal hourly compensation, the factor most directly tied to the unemployment rate (the real one, which is not necessarily the version published by the BEA) is growing on average at the lowest pace since 1994. The 4-quarter year-over-year change is less than 1% now, which is worse than at any point in 2008-09.

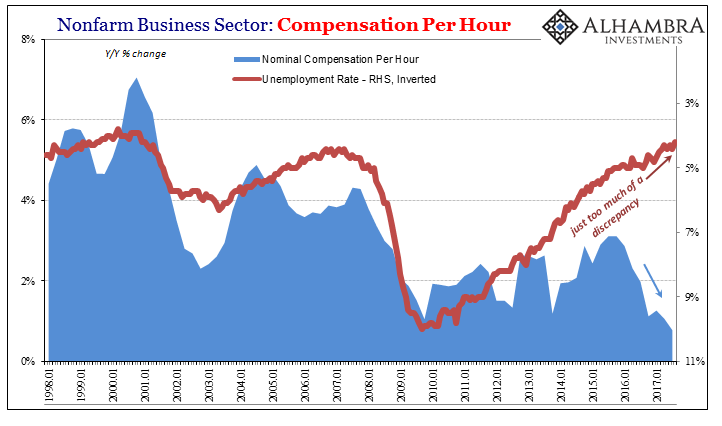

Now that doesn’t mean the economy is falling off a cliff or is about to, only that the labor market is much, much weaker than is otherwise indicated by most of the BLS statistics – including those trying to measure slack. For Economists and policymakers (redundant), this is all taking place at the very same moment the unemployment rate has dipped significantly below all estimates for where full employment “should” be.

This is a contradiction that cannot stand; either the unemployment rate is the correct view, or this wage and compensation data is. It cannot be both any longer.

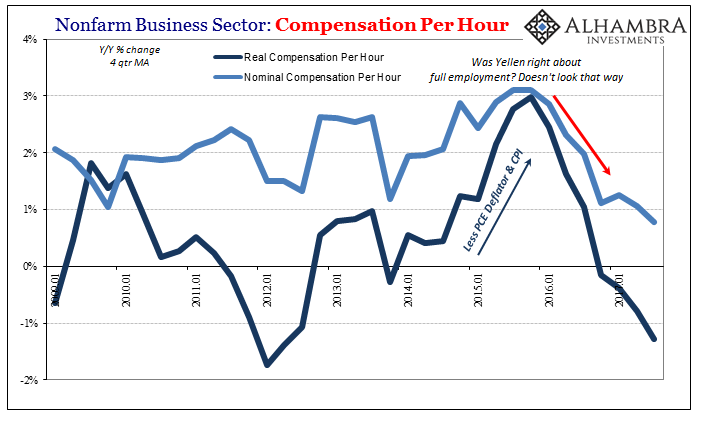

Because of the lack of growth for wages in nominal terms, real hourly compensation has been negative (year-over-year) for four quarters in a row, a full year. That length of time is sufficient to overcome any questions that might arise given the short run noisiness of the data. American workers are much worse off for the 2015-16 downturn.

Leave A Comment